Features

Features

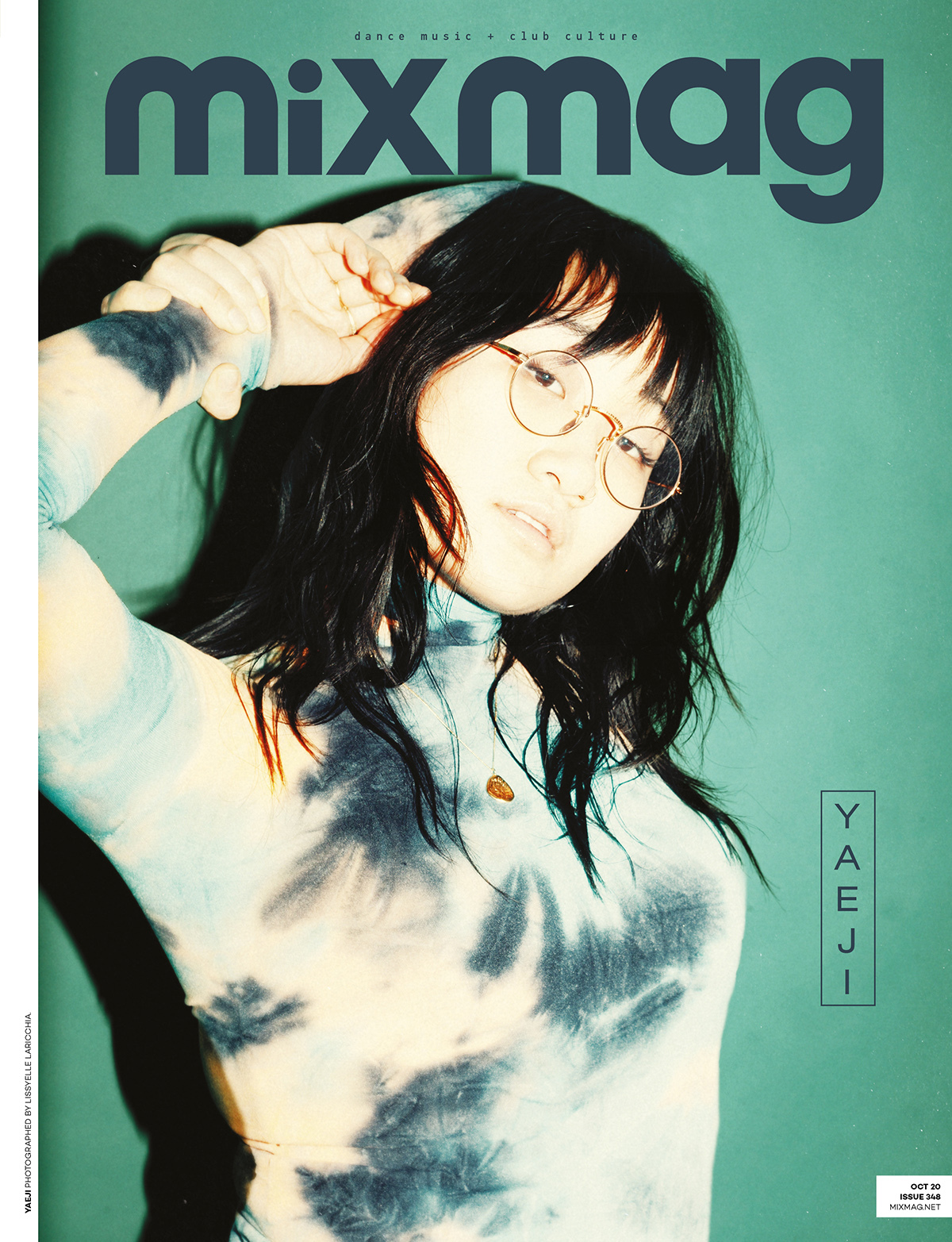

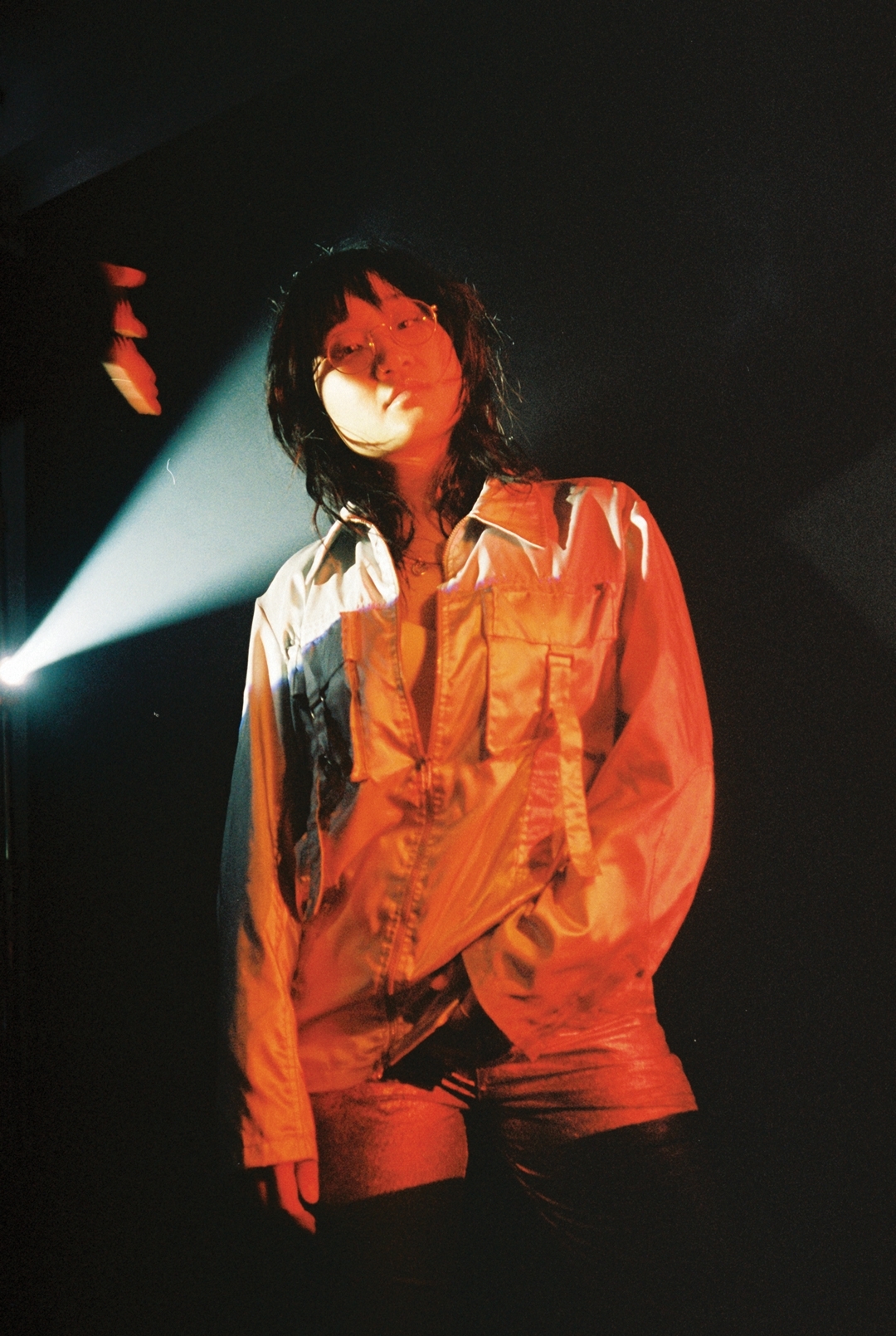

How Yaeji found her voice

Michelle Kim talks to Yaeji about community, collaboration, self-discovery on the dancefloor – and how a trip back to Korea sparked a creative rebirth

Kathy ‘Yaeji’ Lee is wielding her chunky red thermos like a designer accessory. It’s a rainy Friday night in early March when we first meet for what is unknowingly our last meal at Kichin, the trendy Korean fusion restaurant in Brooklyn that permanently closed in June due to the COVID-19. Unaware that the pandemic will soon cause New York to go into lockdown, the 27-year-old musician is giggling about her grandma-like behavior of carrying around ginger tea. She feels under the weather, and the particular timing of this illness is not ideal. It’s just under a month before the release of her debut mixtape ‘What We Drew 우리가 그려왔던’, and things have been a bit “crazy,” as she puts it, her eyes crinkling behind delicate wire-rimmed glasses. Chucking off a giant puffer coat, she turns to the conversation with a gentle focus, asking in a soft voice, “How was your day? Are you hungry?”.

It’s been three years since Yaeji released her first two EPs, and her catchy house bangers laced with pop hooks and hip hop attitude — ‘Raingurl’ being the biggest hit of them all — have swiftly catapulted the producer from relative unknown to an emerging popstar. Both nothing and everything about Yaeji makes sense. Her ASMR-like voice can be at once soothing and stinging; she produces, sings, and raps in both Korean and English; orchestrates hyper-local underground NYC raves, but has fans all over the world; and even her club-ready songs are about her most anxious and meditative thoughts. The fact that she’s able to straddle different worlds, and easily flit in between opposing modes, is what makes her such a captivating figure.

Yaeji’s year leading up to ‘What We Drew 우리가 그려왔던’ looked relatively quiet from the outside. She threw a couple of large-scale parties in NYC and released a handful of tracks and remixes. But as we wait to order our comforting meal of jjajangmyeon and soondubu, Yaeji says that it was actually the opposite. “I was incubating,” she says. “It was a time of creative focus.”

In this self-reflective period, she quit drinking alcohol and became a self-professed “homebody”, left Godmode (the small LA label that issued her first EPs), experienced a life-changing trip to Korea and wrote the songs that would appear on her first full-length project. As a direct result, ‘What We Drew’ sees Yaeji rejecting her identity as a strict house musician, fine-tuning her skills and gravitating towards her natural inclinations to be exploratory, fluid and collaborative.

Right before working on the new album, Yaeji realised that working with others was the “one thing [she hadn’t] been exploring,” she explains, making her wonder if she was too “scared” or too much of a “perfectionist” to do it. She didn’t have to overthink it, though — the right creative partners emerged organically. YonYon, the Japanese DJ who appears on ‘Spell 주문’, is an old classmate from Yaeji’s Korean middle school in Japan; Nappy Nina, the Brooklyn rapper who offers a verse on ‘Money Can’t Buy,’ is someone Yaeji met through friends; while Victoria Sin, the drag artist who features on ‘The Th1ng’, first connected with Yaeji when they were both performing at a performance series curated by London’s Serpentine Gallery. As she continues to elevate the creatives around her, Yaeji seems to present a model of a new kind of artist, whose stardom comes more from her willingness to share the spotlight.

The project’s free-wheeling, genre-blending nature proves that she shines best when she doesn’t have to be any one thing at any given time. “I’m trying to distance myself from [making one genre] because that can easily limit you as an artist or a person,” she says firmly. “I never thought of myself as just a house music producer before.”

This predilection for eclecticism is even apparent in her outfit, which seems equally suited for lounging at home or hitting the dance floor. She’s wearing a blue tie-dye Woodstock t-shirt gifted by her mum, loose forest green pants and a baseball cap that sports the logo for Dadaism, a Korean-owned creative agency that helped produce the music video for the title-track from ‘What We Drew’. When she takes off the hat, she shakes out her cool-girl mullet and points to the logo with a slender finger.

For the visual, she spent time in Korea with a crew of all Asian women that made her feel “secure as a Korean femme for the first time”. “Being able to connect with Korea, accepting it and feeling proud of it was so important for all of us,” she says with a palpable sense of gratitude, taking a slurp of spicy stew. The resulting video features all of them in matching outfits and dancing around a colourful shrine for a giant onion like they’re jubilant pre-teens on a sleepover. (It ended up bringing forth Yaeji’s new name for her fan base: onions.) The trip was so emotional that Yaeji and her friends started a group chat where they would send photos of themselves every time one of them would spontaneously burst into tears. “We have a collage of all of us crying,” she says, chuckling. “It’s really sweet. The fact we can even do that feels so good.”

“I’ve realised recently that all of us are super, super youthful,” Yaeji says of her collaborators with a beaming smile on her face. “Everyone is always laughing all the time. That’s indicative of so many things – just the fact that there is so much love and positivity [amidst] all the pain that we go through, all the chaos that we experience.”

In the past few years, Yaeji has been working on unpacking her childhood, which she admits she blocked out most of from her memory. Her parents have long been business owners in the K-beauty industry, which forced the family to move around a lot when she was young. Young Kathy Lee spent parts of her adolescence in Flushing, Queens, where she was born, until she moved to Atlanta, Georgia, where she was the only Asian American in her school, and then Korea and Japan. Being a constant cultural transplant was jarring. “Every marginalised person experiences it differently,” she explains while picking at a bowl of rice, “but being multicultural is extra layered and complicated because you’re a part of different things. It’s hard to know how much you’re a part of each thing, percentage wise. You can’t quantify it.”

An only child who had to spend a lot of time alone, she became introverted to the point where her posture even became hunched — a protective turtle shell. Despite the trauma that came with her upbringing, Yaeji says it caused her to become “extremely open-minded” because she didn’t feel like she had to fit any kind of mould. “I realised that something that means a lot here doesn’t mean shit there,” she says.

Though her adolescence was largely marked by isolation, she does recall early memories of connecting with others through music, whether it was performing in karaoke rooms with her parents (‘Kiss Me’ by Sixpence None the Richer and ‘Lucky’ by Britney Spears were her go-to karaoke songs) or rallying with fellow classmates around the music style of bossa nova electronic and Shibuya-kei — made popular in the early 2000s by the band Clazziquai Project. The first time she led a group of people, though, revolved around a different hobby. In high school, she created a “Marketing and Advertising club”, mostly out of a “passion for graphic design” and partly to bolster her college résumé. She oversaw the members, she admits with a bashful grin, who would create posters for other clubs.

It wasn’t until she attended college at Carnegie Mellon in Pittsburgh that she found a community that fostered her musical expression. While majoring in fine arts, Asian studies and communication design, she discovered the world of college radio. Hosting her own show planted the seeds for her eventual career as a producer and performer. She recalls that her mom would always compliment her “beautiful voice”. But when she started doing radio, she found that people “responded really well” to her whispery intonation. “That gave me a lot of confidence to use my voice as an instrument,” she says.

Around this time, she experienced her indoctrination into nightlife after attending Hot Mass, the long-running techno party held in the same building as a gay bathhouse. Her rave awakening caused her to realise that being in a small space surrounded by people was something that was conducive to introspection and “realising things about yourself,” she says, adding, “It could be anything, like understanding where you are in your life better, understanding your anxieties better, maybe understanding your communities better.” She compares clubbing to her experience attending Christian summer camp as a young girl, when the kids would stay up all night doing various activities and reach a state of gleeful euphoria.

When she moved back to New York, she would go out up to five times a week, eager to check out the diverse array of DJs the city had to offer, from house to experimental, leftfield bass. She watched everything closely — from how the DJ was mixing to the lighting and soundproofing of the space — and her observations helped inform how she wanted to throw her own parties. “Everyone has their style, but I resonated with DJs that have a great time when they play, whether it’s them smiling or bouncing a lot.”

But for every good night out, there were bad ones. Not every party that she attended felt inclusive, which drove her to make sure her own raves were safe for queer people of colour. “When the crowd is predominantly white straight men, it’s very uncomfortable for various reasons,” she says. “It ranges from random people hitting on you to people taking up too much space where it almost feels violent. They’re expressing too much without consideration for their surroundings.” It’s this kind of ostracisation within the dance music industry at large that drives Yaeji to make music with and for marginalised folks. “All of us are coming from different types of traumas,” she says, “but what we share is that we all experience pain and through that we can empower each other and create a family together.”

Chatting with some fans of Yaeji online, it’s clear that the way she makes space for QTPOC in the dance music world appeals to her fans on a broader scale. Marcus, a 23-year-old Yaeji fan and university student, says that her attitude towards inclusivity has rubbed off on him. “She makes it a point to support and include these groups that are often clowned, which makes [her fans] perpetuate that mindset,” he explains. Lila, a 20-year-old transgender fan from Detroit, says that she feels seen and included by Yaeji, especially since the musician has pledged proceeds to Black Trans Femmes in the Arts, a collective that provides resources to Black trans and nonbinary femmes.

The way that Yaeji creates a community out of her circle of collaborators has now become one of her defining features. For dessert, she’s ordered a kabocha squash pie that she finishes in just a few bites, as she explains how her friends have helped her loosen up and chuck away self-doubt. One song was particularly liberating to record: ‘Free Interlude’, a lo-fi hip hop track featuring three of her close friends who aren’t serious musicians. She recalls thinking, “Are people going to think this is whack?”. But it captured a sense of fun and camaraderie that she couldn’t keep back. “Including it [in the album] feels really empowering because that means I’m taking myself less seriously, in a good way.”

Her newfound confidence towards music making is part-and-parcel with the fact that she’s embraced Korean in her songs — a huge step for the singer who has said in interviews that the language was a kind of shroud for expressing thoughts she didn’t necessarily want all her listeners to understand. ‘What We Drew’, by comparison, features whole tracks solely in Korean, in which she leans further into the angular and percussive aspects of the language. “I am so comfortable now for people to learn more about this language and understand exactly what I am trying to say,” she smiles with pride. “It’s so beautiful texturally. It has so many more mountains, and hills, and rivers, and angles.”

After we wrap up our meal, we pause outside the restaurant to shelter from the drizzle. We part ways thinking that we would see each other again the following week at a dance rehearsal, which was meant to prep for her live set that was originally intended to incorporate elements of the Afro-Brazilian martial art capoeira and traditional Korean fan dance. Of course, both the practice and the tour were cancelled — like everything else in 2020.

The next time we greet each other, it’s through a Zoom screen. It’s now early October, and Yaeji is in Korea visiting family. She arrived there in mid-August to be with her ill paternal grandfather, before he passed away from long-term health complications. “I feel really soft and really emo,” she says, explaining that her trip has been spiritually demanding due to her first-time experience of participating in a more traditional Korean-style funeral for her grandfather. It was “exhausting” but “beautiful”, she says, adding that “the intensity in which they carry out the funeral helps you process it better.” Despite it all, she seems characteristically thoughtful and even-keeled as we chat about the whirlwind of a year it's been.

It’s been hard for her to process the fact she did actually release a project this year, she admits, mostly because she hasn’t been able to physically meet and interact with her fans. Instead, she’s been doing some virtual sets, like her brilliant “at home” Boiler Room set that features digital cameos from her collaborators, and more recently, her monthly NTS radio show called Kraeji, in which she intentionally pushes the work of QTPOC artists and directs people to buy their music on Bandcamp. She considers it a small, tangible, long-term action that can go a lot further than the sort of performative black boxes some dance music professionals were posting in June, when Black Lives Matter protests were sweeping the globe and calls to dismantle systemic racism began reverberating across industries. “These are thoughts we've had every day prior to this happening,” she says. “But we finally got momentum and people were paying attention. So I think to a lot of us, it was a no brainer to be like, ‘Okay, let's just shove it in and feed this information while everyone's looking.’”

She’s cognisant that she has a “really powerful platform” as a musician with a substantial following, but she’s still meditating on a singular purpose or message to her music. “I don't even have an album yet,” she points out with a chuckle, adding that she thinks she’ll figure it out as she matures. Given that with each project so far, Yaeji has continued to unearth more and more dimensions within herself, there’s no doubt that she’ll get there soon.