Features

Features

“You can trump bad hair with a good pair of shoes”: DJ Harvey on style, surf, and building the ultimate nightclub

A sitdown with the legendary selector during his month-long residency at Klymax, the club he built “from ground to sound" with Potato Head, Bali.

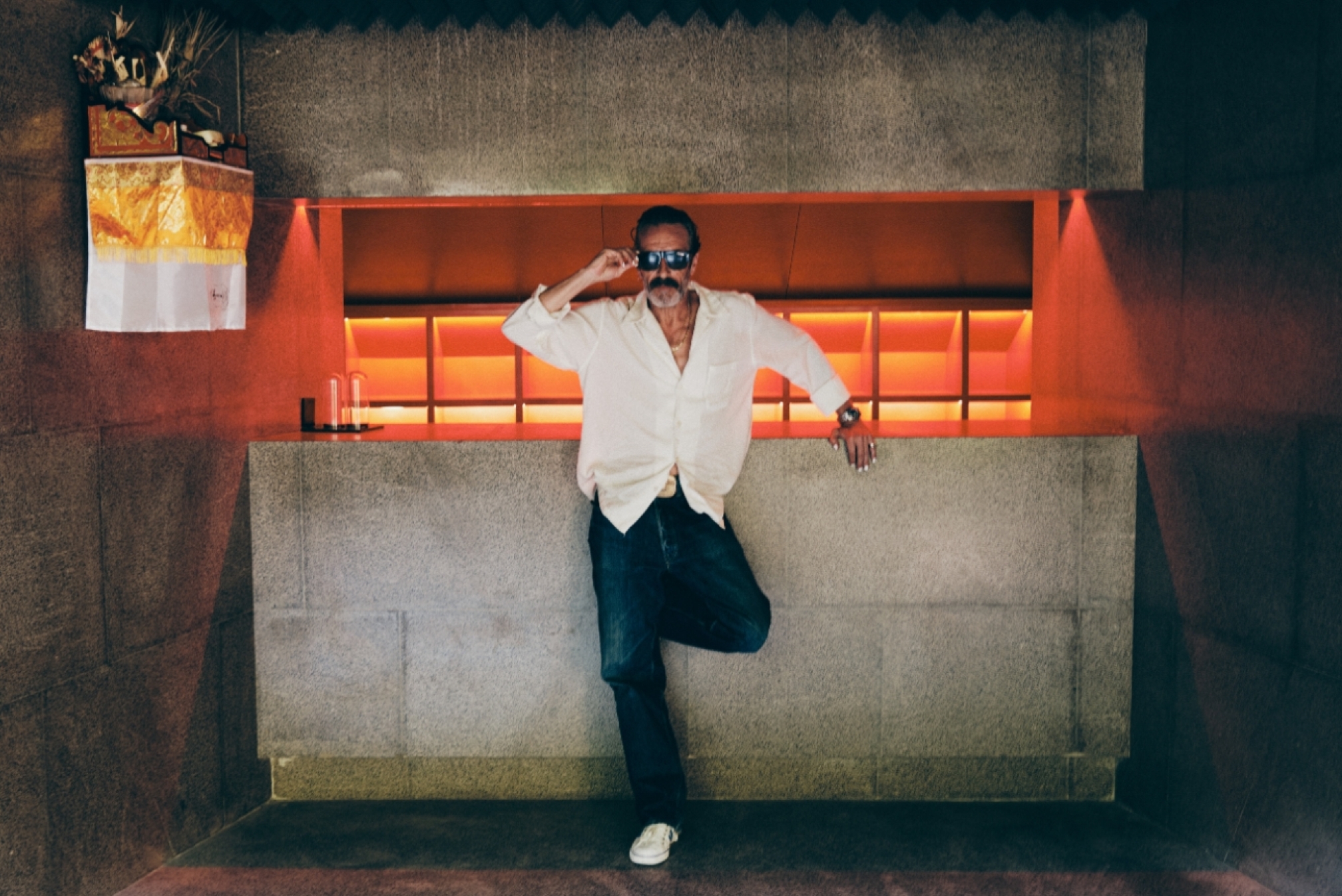

“I’m quite a kooky surfer, but I really enjoy myself,” says DJ Harvey, showing off his custom-made ‘Klymax’ longboard – named after the newly opened nightclub and multifunctional venue he designed alongside Bali institution, Potato Head. “I’m not doing flip tricks and all this kind of stuff, I’m going down the line with a flow and style that I learned from the Malibu masters.”

The LA-based had just dusted off his month-long Klymax Discotheque residency, where he’s been putting the state-of-the-art JBL system through its paces all night long every Saturday. The sun is shining after an unusually drawn-out rainy season, and Harvey is basking in the afterglow of a morning surf. Still aching from the exertion, he’s passionately describing one of his surf heroes, Malibu legend, Jared Mell. “When you see him surf, it’s effortless. It’s like he’s more worried about his hairstyle than the wave.”

Does Harvey worry about his hair when he’s playing? “Bad hair is bad hair, man. But you can trump bad hair with a good pair of shoes.”

When pitched with the notion that parallels could be drawn between his surf and DJ techniques, he appears initially unsold. “Maybe,” he says, after a pause. “As I put myself out through the medium of surf or art — be that DJing, painting, making movies or whatever — I think style is an essential part of all of that. Style is everything as far as I’m concerned. If you do something stylishly, you’re doing it well.”

Harvey has long qualified for legendary status. As a DJ, producer, and scene provocateur, he inspires a cult-like adoration from his fanbase reserved for only the tiniest portion of artists. His sets are a synonym for quality, always playing for the crowd while introducing music you don’t know but wish you owned. The breadth of his musical knowledge, the imagination with which he crafts his sets, and the style and swagger he exudes whether inside or outside of the booth endow him with a quasi-mythical edge.

There’s a glint in his eyes hinting at a propensity for mischief. Informed and interested in all manner of subjects, he’s sure of his opinions and unafraid to express them. He’s a larger-than-life character who dwells in rarefied topography as an artist and a presence. While staying at Desa Potato Head, he chats freely with passers-by, staff, and team members. He seems at ease in Bali, enjoying the surf and setting as much as the musical playground he helped create.

His Klymax residency has been an opportunity to flex in an environment where every imaginable variable meets exacting standards acquired during a decades-long career at the pinnacle of the dance underground. Bringing his freeform, expansive sound to his temporary island home, the sessions have seen him blend esoteric burners, forgotten gems, unreleased promos, re-touched classics, and more – joyfully traversing eras and stylistic boundaries. Psychedelic sweeps surround as they glide between the stacks. Enveloped in sound, the dancers strut under his spell throughout the meandering sonic journeys.

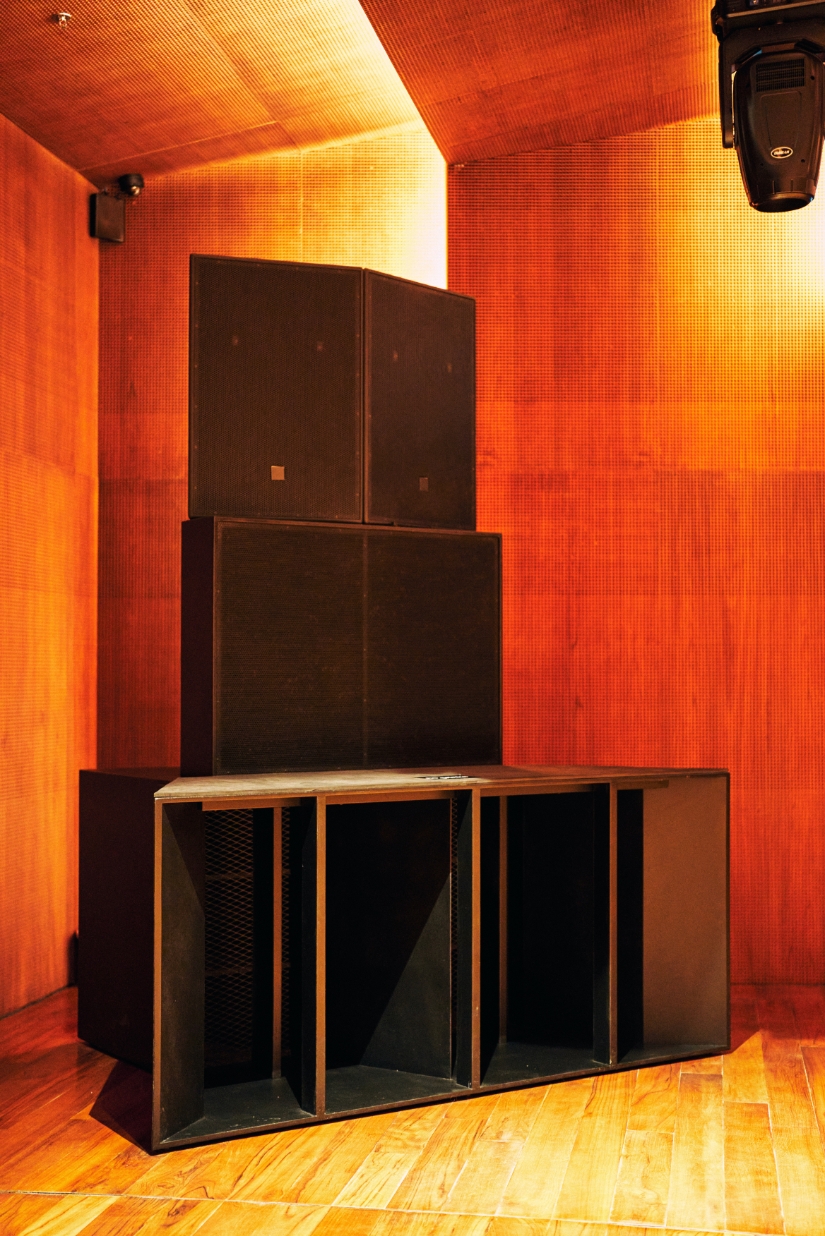

The system was built to Harvey’s specifications (by respected sound designer George Stavro), and all of his music translates brilliantly through the speakers, from the organic crunch of vintage disco soul to the low-end throb of modern four-to-the-floor. A natural raconteur, Harvey’s oratory exuberance is matched by his sonic storytelling. With this in mind, one of his audio prerequisites was that every musical nuance be discernible on the Klymax floor – not least the vocals. “I talk through the music,” he says. “I don’t play a lyric that I’m not intending to communicate at that moment.

“I don’t play ‘Get Down Saturday Night’ on a Friday night.”

As is the case for a large portion of the subcultural purveyors to have arrived in Bali in recent years, it was Potato Head that provided the gravitational pull for Harvey. Impressing when invited over to play at the then-beach club (now a fully-formed desa – the Bahasa word for village), he was asked back for repeat shows. It was on his third visit that he reconnected with Dan Mitchell, who was working at Potato Head as Creative Director (and who recently returned as Chief Creative Officer). The pair first met in London, and their paths had crossed at various intervals and on various continents before their auspicious island reunion.

Alongside Potato Head founder Ronald Akili, Dan approached Harvey with the idea of adding a nightclub to their burgeoning project, asking if he’d be interested in helping to bring it to life.

“Fuck yes,” was the response.

This wasn’t the first time Harvey had been sized up to collaborate on a nightclub project. “I get asked three times a year to build a nightclub for someone, but it never goes anywhere. [Potato Head] stepped up and made it happen, that’s the big difference.”

He worked with a team of architects, designers, and audio engineers to fulfil his vision, and it’s the combined knowledge of all involved that sets the venue apart. “There’s nothing in Klymax that you can’t get delivered on Amazon Prime tomorrow afternoon. It’s taking readily available ingredients and making a knickerbocker glory out of them.”

He’s quick to defer due credit to behind-the-scenes experts who helped bring the concept to life. “We couldn’t have done it without a great team,” says Harvey, taking a moment to salute the “unsung hero of the project,” Potato Head architect, Ade Herkarisma. “Quietly, he is the main guy who brought my ideas through the architects and the acousticians, all the boots on the ground, directing the construction to let it be what it is. I had to give him a big hug and a kiss because he’s a graceful guy who gets things done.”

The sound, space, and experience more than live up to the billing. On club nights, the music is not only beautifully detailed, it’s played at a volume that dispels the idea that dance music has to be played at ear-splitting levels to function. It’s perfectly possible to have a conversation in the middle of the floor, all frequencies arrive at the eardrum without causing undue fatigue. When entering Klymax before the music starts, the lack of reverberation in the room is striking: the acoustic treatment — as well as shaping the look of the interior — is as important as the quality of the sound system when it comes to delivering unblemished audio.

Read this next: Potato Head debuts a DJ booth made from 564 kgs of recycled plastic

The DJ booth is perched high above the crowd, consciously removed as a focal point. “The DJ centre stage on the pedestal throwing a cake with a silly hat on exists because DJs are boring to look at,” says Harvey. “I went to clubs for 30 years and most of the time I had no idea where the DJ was. The focus was on the people, the dancing, and the social interaction. The DJ was just supplying the soundtrack.”

With Carl Craig, Ron Trent, Nina Kravitz, Kyle Hall, Jane Fitz, Danilo Plessow, Lakuti and Tama Sumo among the artists to have graced the Klymax booth, as much thought has gone into providing the ideal environment for the performers as for the partygoers. The monitors feature the same drivers as the house system, so the DJ knows exactly how their music sounds on the floor. There’s a well-equipped green room, a shower, a bed, and, perhaps most importantly, a toilet. “Half the clubs in the world, if you want to take a slash as a DJ, you have to put a long one on and walk across the dancefloor.”

When discussing the club, his passion is palpable. Klymax by name, there’s a strong case to be made that the venture sits somewhere at the zenith of his life’s work. Long after the doors were opened (last New Year’s Eve, with a barely announced, sold-out all-night Harvey set), he continues to be instrumental in the club’s direction. He rubber stamps every booking, nurtures the Indonesian-only resident DJs, and co-curates the films played on cinema nights. Bilateral communication between LA and Bali is constant.

The experience poured into the venue comes from a lifetime surrounded by music. Now approaching his sixtieth year, Harvey’s musical origin story started in his fenland childhood home of Little Thetford in the East of England. His mother loved to dance, transitioning from a ‘50s rocker into a jazzer while amassing a “wonderful selection of rock and roll and trad jazz” records to which Harvey had full access. His “incidentally into hi-fi” father had only three records: Best of The Beach Boys, Best of Helen Reddy and Best of The Safaris. “Again, fen cowboys, fen surfers. These fantasy worlds. Some of my favourite records from six years old were ‘Surfer Joe’, ‘Wipeout’, and ‘Walk Don’t Run’, these amazing surf records. It’s funny that so much of the music was surf music, I never really thought about that before now. You know, it was in me.”

Read this next: Bali beyond Instagram: Dita is uplifting a new generation of DJs in Indonesia

It helps no end for talent to be nourished, and Harvey’s parents were quick to encourage his creativity. When he started “bobbing around with pencils and clingfilm over saucepans,” his mother suggested buying him a drum kit, and by the age of 12, he was “hanging out with the big girls” playing in punk bands in London and Cambridge. His bandmates were in their late teens, and it was left to their respective girlfriends to look after the fresh-faced drummer while on the road. “We’d go in the pub and order an orange juice, and when no one was watching, they’d pop a vodka in it for me for Dutch courage and I’d get on the drums. It was the glory days.”

Eventually tired of the challenges, compromise, and ego conflicts of playing in a band (“being in a band is like having four girlfriends”), Harvey was open to finding new ways to express his musical instinct. He was surrounded by disco as a youth, at community centres, under-18 events, and school discos. But it wasn’t the DJ who first caught his attention. “The DJ just took requests,” says Harvey. “I was into the lighting guy. He had strobes, a bubble machine, a projector, smoke and all that stuff. So I really studied the lighting guy, ‘cause he was making these fun atmospherics and he was his own guy.”

It wasn’t until the rise of hip-hop in the ‘80s, witnessing DJs juggling beats, that Harvey realised he could “get all the jollies at once” behind the decks. “I was like, okay, I’ve got rhythm, I can manipulate rhythms via turntables, I can be a one-man band and play the music that I couldn’t actually play in a band. I can’t play guitar like Jimi Hendrix, but I can play a Jimi Hendrix record. I could please the people without having to ask four mates for their opinions.”

Despite his love of early hip-hop, there was something foreboding about the surrounding scene that prevented a complete connection. New sounds would soon arrive from Chicago with an attitude that Harvey instantly vibed with. “In the ’80s, it was dangerous to go to a [hip hop] nightclub, so when I first went to an acid house club I was like, ‘I have arrived, this is it’. The music was crazy heavy, but people were like ‘Hey buddy, give me a hug.’ The music is as passionate as any music ever made. It’s a unifying thing. You didn’t have to be able to dance, spin on your head or have jazz moves. You just wave your hands around and have a fucking good time.”

Read this next: A trip through DJ booths: 1976 - 2016

He threw himself into acid house wholeheartedly, feeling it was the first new musical form he’d encountered to which he could fully contribute. “I was following punk, I was following hip-hop. With acid house, I could help instigate and be part of the movement. That was very important.”

Fuelled by a sound that inspired him, DJ success came quickly. But it wasn’t until 1988, with a measure of entrepreneurial spirit, that he was able to quit his day job working as a cycle courier in London. He recorded ten copies of a mixtape called ‘Strong Acid’ to sell at local boutiques. “It came with a free acid tab,” he laughs with a rasp. “I sold ten tapes for ten quid each in an hour, made 100 quid in an hour and never worked again!”

Onto a good thing, he continued making the recordings to augment his DJ income. “What with promoting my gig, sending my mixtapes and doing a little DJing I was able to pay my rent, which was nothing really – I was living in Wandsworth in my mate’s cupboard under the stairs.”

Momentum was building, and before long, the “high priests of acid house” from pioneering nights Shoom, Hedonism and Clink Street started to pay attention, booking Harvey for shows before he landed a gig as the first local resident at landmark venue, Ministry Of Sound. “The rest is history,” says Harvey.

Read this next: 30 photos that prove disco balls rule the world

From Monday night at the Zapp Club with his Tonka Soundsystem crew to booking the likes of Larry Levan, Darryl Pandy, Underground Resistance, and Mr Fingers “in a little Covent Garden basement” alongside Heidi at Moist, Harvey’s name was ringing out on the blossoming dance underground. He continued his trajectory throughout the ‘90s, but by the turn of the century, sensing a “shift in clubbing,” a change of scene beckoned.

“One of the greatest anticlimaxes of my life was New Year’s Eve 2000,” says Harvey. “We’d had the ‘raving ’90s’ or whatever, and people, in the beginning, had given up jobs to become full-time ravers. At that point, ravers had to start getting jobs again.” Clubs that had previously run weekly started to open monthly and the rise of the ‘super clubs’ had begun. Having seen plenty of the world while travelling for gigs, Harvey was open to the idea of leaving the UK on a long-term basis. California was somewhere he’d always been drawn to, and when the opportunity to start a new life there arrived, he embraced it. But not without a bureaucratic detour along the way. “I liked it so much, I overstayed my visa. I was like, shit, Hawaii is still America, so I could go and do my thing out there.”

His voluntary island state exile proved eventful. He ran a nightclub, honed his surfing, got married, and received his green card. It was a full 10 years before he would revisit Europe. Absence, of course, makes the heart grow fonder, and, during his extended hiatus from performing on the continent, hunger for Harvey became ravenous. “Nothing advertised me in the world except other people talking about me on the internet, which was kind of a new thing,” he reflects. “The legend of Harvey was born in those ten years. When I came back – the European relaunch, if you like – it wasn’t by design at all.”

Read this next: 48 vintage pictures that capture the early days of clubbing across Asia

The Venice Beach resident has remained in demand since resuming touring, regularly captivating eclectic dancefloors worldwide. His Pikes Ibiza residency is an annual White Island highlight, and the Mercury Rising compilations it spawned have helped his sound resonate with ever-new demographics.

And now, his new subterranean centrepiece is seductively diverting the gaze of the global clubbing community towards The Island of Gods.

Klymax Discotheque is open every Friday and Saturday night, at Desa Potato Head, Bali. Visit its official website here.

Patrizio Cavaliere is a DJ, producer and journalist. Follow him on Instagram.