Features

Features

A trip through DJ booths: 1976 - 2016

The evolution of DJ technology

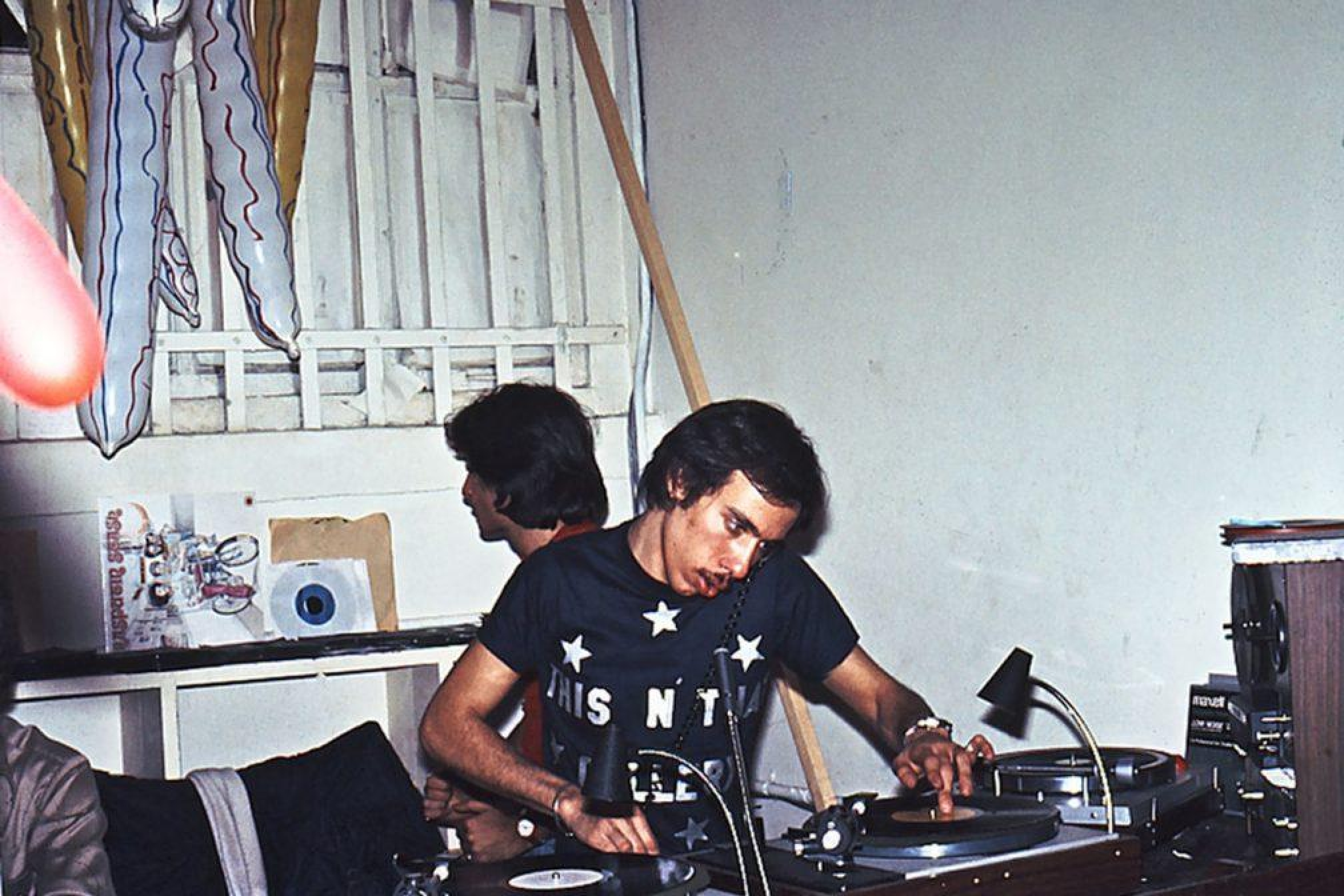

1976

1976 may seem distant in time, but the similarities are a little closer than you might think. Forty years ago, mixing vinyl on turntables was the cool kids’ way to play, but the city councils were hell-bent on shutting down our favourite clubs. Sound familiar? The thriving disco scene of the genre’s capital city, New York, might seem small in comparison to the global monster that is dance music today, but clubs like David Mancuso’s The Loft were battling to stay open as local councils cosied up to the new residents bringing gentrification into the area. While #SaveTheLoft sadly didn’t have Twitter to fight its cause, in the clubs, technology was laying a blueprint for how DJs should play that would last for decades. Although the era’s most famous club Paradise Garage wasn’t to start until the following year, it’s shining star, Larry Levan, was plying his trade at another club called Reade Street. Levan wasn’t just a DJ, of course. He was an all-round club specialist, taking particular interest in the soundsystem and often known to hold up the club’s opening while still stuck up a ladder polishing a disco ball.

The great DJ booths of the era were obsessed with high-fidelity audio, and DJs like Larry paid as much attention to adjusting the room’s speaker systems and acoustics as they did to the records played. At the centre of most booths was a Bozak rotary mixer and, side by side, a pair or in some cases a trio of turntables. Technics 1100 or 1200s were mostly used by the smaller discos and block party DJs, but for influential DJs like Levan or Mancuso the Thorens T125s belt drive turntables were preferred. Thorens, a German brand of turntables, were famed for being difficult to mix on. “Most DJs wanted to have what Larry had in the booth, but if you grabbed the record platter [of the Thorens] too hard, the table would stop,” explains Joey Llanos, a sound technician at the Garage and later a DJ now best known for playing Paradise Garage tour nights. “They were manual, but incredibly smooth.”

Instead of USB CDJs, DJs relied on a Technics 1505 reel-to-reel tape player to throw in edits of tracks or new music on the fly. Often spending hours splicing and cutting tape to extend the instrumental breakdowns or bridge sections of songs to create the trackier instrumentals that drove dancefloors wild. “He used Delta Lab digital delays, which we first heard at the opening of Star Wars at the Loews Astor Plaza in Times Square,” says Joey. “We inquired about the sound processing after we went there; next thing you know we were using them at the Garage. Whatever Larry wanted for that booth, he got.”

1986

A decade on and New York’s beloved Paradise Garage was beginning to come apart at the seams. In the disco, Levan ruled as ever and the celebrities clamoured to join its faithful, mostly gay, ethnically diverse dancefloor – but drugs and AIDS gnawed at every corner of the club’s success, leading to its eventual closure a year later. The booth remained an audiophile’s temple with an expanded array of tools to play with. Turntables and a tape player still ruled, and a Urei 1620 mixer had replaced the Bozak mixer. A custom-designed crossover allowed Larry to attenuate the different frequencies of the records according to the room’s needs. The DBX Boom Box allowed him to boost the bass, while other specialist tools like the Acoustilog image enhancer allowed him to play with a track’s stereo field or add delay or reverb thanks to the Deltalabs Acoustic Computer. Meanwhile, over in Manchester, the DJ booth of the Haçienda where Mike Pickering (pictured) held court, the club that would later be heralded as the UK’s greatest wasn’t enjoying quite the same attention to detail – although it had seen worse days. In 1983 the booth was squirrelled away to the side of the stage with only a tank-style slit window to see the crowd and an antiquated Aqwil mixer with no faders. Instead, it had an selection of two automatic mix buttons which either jumped instantly from one channel to the other or slowly transitioned automatically between the two. Thankfully, things improved in the mid-80s with the relocation of the booth to the balcony and the addition of the Formula Sound Pm-80 mixer. This revolutionised the resident’s ability to mix up proto-house with other styles thanks to faders and per channel EQs.

1996

Modern dance music was in full swing by the 1990s. Acid house had ended, but DJs like Sasha and Tony de Vit (pictured) were establishing the cult of the superstar DJ. Unlike the leading booths of the 70s, the DJ’s concern was less with the club’s sonics and more about mixing tunes on the ones and twos and getting carried away in the booth. Super-clubs kept the sound processing gear away from the direct control of the DJ. Technics 1200s or 1210s were by now industry standard. Tape machines were no longer required as the top-loading CDJ-500 had been introduced a year before and was the tool of choice for playing tracks fresh from the studio, acapellas and sound effects.

While CDJs would later go on to run Technics out of most booths, the 500s were tricky to mix with thanks to a clunky jog- wheel that couldn’t yet mimic the effect of a turntable – and for most of the 90s, Technics remained the main player of choice. The 500s did, however, have Master Tempo, the button that kept tracks in key when you changed pitch. Pioneer’s other great innovation was the DJM 500, a four-channel mixer with terrible sound but which became an instant hit thanks to an effects section that could sync with the BPM of the track playing. Cue pissed DJs the world over drunkenly thundering the delay effect until your ears threatened to melt.

2006

The direction of the DJ booth had already been changed once by Richie Hawtin in the 90s with his ‘Decks, FX and 909’ CD. In the mix (and later on his Mixmag Live CD) Hawtin used effects and the TR-909 drum machine to mutate a DJ mix into something new and different. It wasn’t an entirely original idea – DJs like Larry Levan had been experimenting with effects a lot earlier – but in the early 2000s Hawtin went a step further by helping give birth to Final Scratch (which later morphed into Traktor Scratch), a system of DJing that used control vinyls to play the music on your laptop via turntable. And so a nightmare – and an epiphany – were unleashed simultaneously. As each club system differed wildly, often leading to complications with its set-up, normal DJs became plagued by their laptop colleagues fumbling with wires and asking to play one more track as their laptops failed to sync with the vinyl code being emitted. Tour managers went from being rare commodities to standard fare for the biggest stars as DJs relied on their trusted sidekicks to figure out for the tenth time that weekend why the hell nothing was playing out of channel two. On other hand, when Traktor vinyl worked it revolutionised the DJ’s life, allowing them to bring their entire record collections on the road and add effects or loop all within this new, neatly synchronised world of digital DJing. Those who couldn’t handle the technical bother were being very capably seduced by the ever more powerful CDJs. DJs like Erick Morillo (pictured) or James Zabiela became masters of the loop and cue function, and Traktor wasn’t the only thing to polarise clubland.

2016

Earlier in the 2000s another Hawtin-associated product, the Allen & Heath Xone mixer, went head-to-head with Pioneer for the hearts and minds of the headphone-clad elite. The easy-to-use, all-analogue and great-sounding Cornish mixer was to usher in a new trend that would bear fruit years later in the analogue revival – and indeed in Richie’s own MODEL 1 mixer (see p.74). But that change would take some time to happen. In the 2010s digital DJing had gone even further as Traktor turfed out control Vinyl in favour of single deck controllers like the X1 –and big-room masters like Marco Carola, Loco Dice and Luciano were seduced by its ability to combine loops of tracks into endless on-the-fly remixes and saturate breakdowns with more effects than ever. Beatport had become the main arena in which producers battled to out-sell each other, and notch their way up DJ polls. DJs had long since dumped actual CDs for USBs with the arrival of the CDJ 2000, and Traktor’s vinyl loving followers flocked to Pioneer and its accompanying software, Rekordbox. The Digital DJ controller became the hottest bedroom DJ toy as consoles were mutated with sample pads and syncing threatened to finally kill off the art of beat-matching so painfully cultivated by the New York DJs of the 70s. For many, though, something just didn’t feel right. Endlessly scrolling for tracks in Serato, Traktor or on CDJs had scrambled the memories of DJs who now relied on playlists to tell them what to play. And the super-clean, synchronised world of the digital DJ became too sterile for many to stomach. Disco, house and techno purists like Ricardo Villalobos and Harvey were all along still playing vinyl and having to contend with older and older Technics in clubs that sometimes lay unused for weeks.

But the signs of a shift for a breakaway tribe of DJs back to the world of analogue were heralded by the steady resurgence of vinyl. Sales of records, which had reached an all-time low in the mid-2000s, now became another sign of the DJs’ rebellion against digitalism. Like the Xone mixer, the hands-on joy of mixing records and tweaking synths brought the world of tangible music and audiophile sound back into contention, with DJs like Motor City Drum Ensemble (pictured) leading the charge.

Represses of popular vinyl releases can now match or exceed the number of purchases it takes to make a track

No 1 on Beatport, and being No 1 on record buying sites like Juno or Decks.de is just as important a production publicity crutch. Rane celebrated this new trend with their MP2015 rotary mixer which brought the beauty of the Ureis and Bozaks

of the 70s and 80s back into the spotlight, and Technics reopened their doors for business. For some, the art of DJing had come full-circle, back to where it had begun in the 1970s: pulling out a record, and letting the music do the talking.