Features

Features

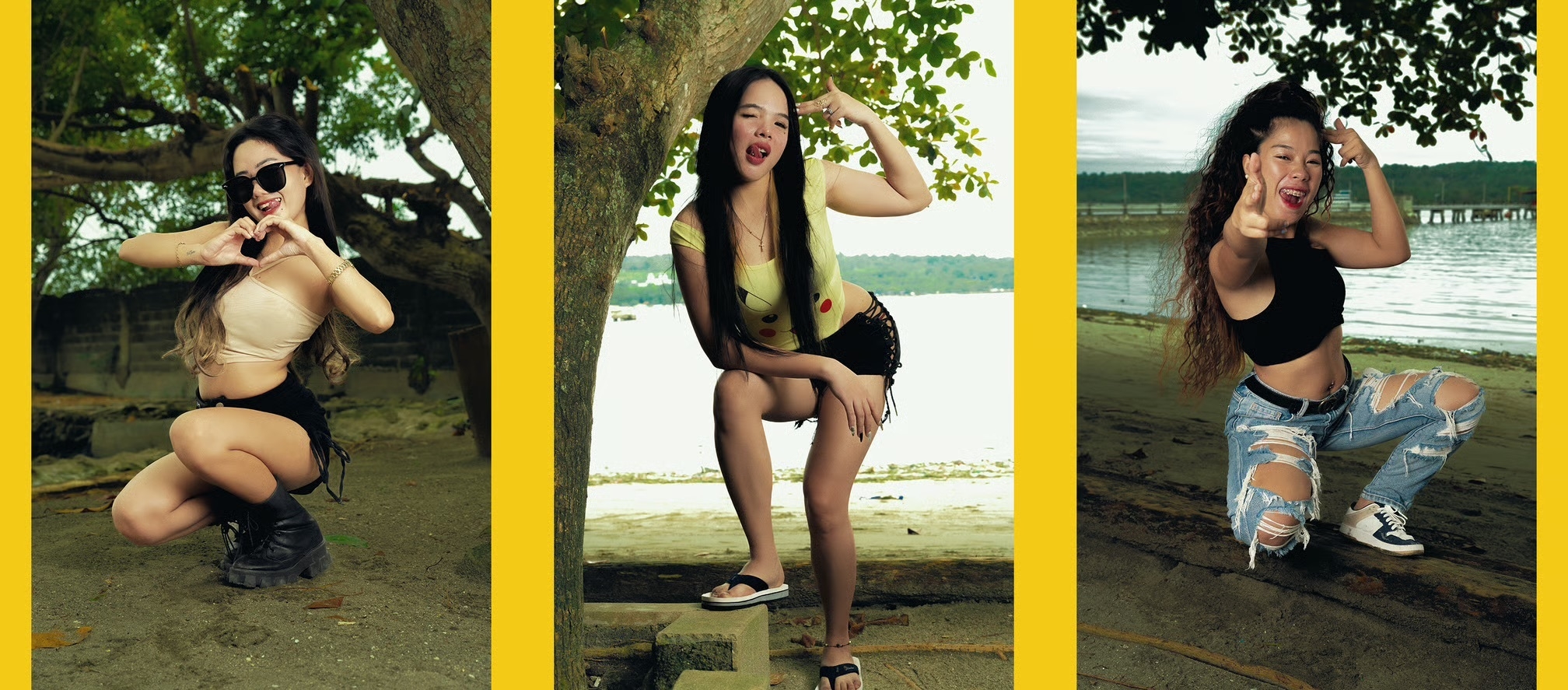

The Budots Three are leading Filipino dance music’s world takeover

Forged in the slums of Davao City in the Philippines, budots was largely sneered at for its unsubtle, maximalist sonics and associations with gang culture. But recent virality has reframed its image, and with a new genre-showcase album landing on Eastern Margins by The Budots Three – DJ Love, DJ Ericnem and DJ Danz – it’s set to takeover dancefloors around the globe

In Davao City, through a winding maze of narrow backstreets and alleyways, once sat a couple of rows of coin-operated desktop computers in a room. With plastic chairs, webs of wires and cables snaking up and around the walls and ceilings, and a mounted fan keeping air moving, it was like any other small internet café in the Philippines in the 2000s and 2010s, where people would go to check their emails, message friends on Facebook, or check on their crops on FarmVille.

Humble, but perhaps fitting surroundings, for the birthplace of a genre that has grown to become a global sensation. In recent years, budots has exploded from an underground, often maligned street-style sound and dance in Davao to a viral social media trend, and now a club sound recognised across the world. The internet café in question was the home and business of Sherwin Calumpung Tuna, AKA DJ Love, the genre’s main originator and pioneer, where for over a decade he’d sit in his boiler room office and craft racing, in-your-face music on early iterations of FL Studio.

Now, with the release of ‘3-Hit Combo!’ – a new genre showcase record on mighty London label Eastern Margins, featuring music by DJ Love alongside fellow pioneers DJ Danz and DJ Ericnem – budots looks set to continue its expansion and take over nightclubs and dancefloors far beyond the Filipino archipelago.

Tuna first bought the internet café in the mid-00s, when he began looking for a new challenge. “I’d been a dance choreographer since 1996, and my group stopped because all of the members had families,” he recalls. “I was so bored, and opened the internet café, but I wanted to make people dance again.”

The term ‘budots’ itself stems from the street dance it is most associated with, which has origins in the culture of the Sama-Bajao ethnic group – a historically nomadic seafaring people in Southeast Asia. Featuring a bent-leg, often full-squat stance, it sees dancers sway from side-to-side at half-time, with knees opening and closing to the beat. In decades past, it was performed to the backing of foreign music – hip hop or chartbusting Eurotrance, in particular – but calling upon his background in choreography, Tuna set out to retrofit and create music that specifically fit the budots dance.

Read this next: The year that budots broke: the Filipino spirit set to 140BPM

Its results were 140BPM, up-tempo, Amen break rhythms that sit somewhere between hip hop and techno, driven forwards by pumping trance basslines. On top, wild synths provide the melody. At first listen, it sounds heavily electronic, as if it’s pure computer music, but Tuna explains that really, budots’ sirens and whistling sonics known onomatopoeically as tiw tiw are the sound of Davao City. “We live in a squatter’s area in the Philippines – it’s a very poor community,” he says. “You could hear neighbours quarrelling, dogs barking, birds singing, engines revving and tokay lizards calling. Everything that I heard, I’d record it in my Walkman, and then remix it into my music. It’s autobiographical.”

Tuna was also a youth council member in his local Sangguniang Kabataan (SK), organising soundsystems for Barangay Fiestas. At these neighbourhood carnivals, where local culture and community are celebrated, he’d fashion a DIY, somewhat primitive DJ setup and play out the new music he’d made. “I started with a very, very old turntable, a karaoke tape and a DVD player,” he explains. “I’d stop the CD and then get the other one playing.”

But despite the fun and positivity, the music and culture wasn’t always well received. For years, budots had a reputation tied to drug use and gang violence. The word ‘budots’ itself roughly translates to ‘slacker’ in Visaysan, while some believe that the loose-limbed nature of the dance references inebriation, and in particular, glue sniffing.

Set on the southeast tip of Mindanao Island, Davao City is the Philippines’ third largest city, with large levels of inequality. According to NGO SOS Children’s Villages, an estimated 14% of families in the Davao Region live in poverty. “In Davao, there is a reputation for having a lot of gangs, a lot of crime, and a lot of drug use,” Tuna says. “And its reputation is true – it’s one of the most dangerous places to live in the Philippines.”

Part of that danger also came from the state. Before 2016, the mayor of Davao City was Rodrigo Duterte, who took a hard line against the drug trade, who intensified a war on drugs that ramped up when he was elected President of the Philippines that year. According to Al Jazeera, Duterte is accused of an estimated 30,000 Filipino killings during his tenures both as mayor of Davao City and as the President of the Philippines, and is currently behind bars in The Hague awaiting trial at the International Criminal Court for crimes against humanity.

Tuna aimed to bring positivity to the streets with his music, and keep people away from trouble. In his music videos, his slogan “Yes To Dance No To Drugs” often appears in graphics across the screen, and he has fought hard to break associations of Davao and the budots dance with drug use. “I tried to push budots so people would either be saved from drugs, or saved from being killed in the drug war,” he says. “I can’t really measure how much it’s changed things, but people from different genders, backgrounds and provinces have messaged me saying that if it wasn’t for my music or my movement, they probably would have died.”

Attitudes towards the genre meant that gigging, and therefore making a living out of budots, was difficult. Beyond income from YouTube streams, there weren’t so many opportunities to make money and perform, according to Daniel Lacanilao, AKA DJ Danz, who first began producing budots in the early 2010s, after first coming across it in a karaoke machine. “Budots used to be really discriminated against,” he says. “In clubs, you weren’t allowed to play budots. In Manila, they used to kick you out or ban you from playing budots. Now, there’s more people who appreciate it, and it’s actually cool to play budots in some venues.”

It’s a not dissimilar story to other working class street cultures, and the music that sprung from them in other areas of the world. For a long time, hip hop was associated with gang warfare in the USA, while in the UK, the early emergence of grime in the '00s and drill in the late 2010s saw similar moral panics. Even ghettotech, the blue-collared cousin to techno and electro – which were historically made by middle-class Detroit heads – was often disparaged for its unapologetically lowbrow aesthetic and fun-first lyrics.

But that would flip on its head in 2016, during Duterte’s campaign for presidency, when he was filmed dancing (very badly) to budots on multiple occasions. The videos went viral around the country, putting the genre on the radar of many who hadn’t heard its beeping grooves before, while also making others rethink its associations. How could budots be a druggy dance if Duterte himself is doing it?

With that, came a boom in popularity. DJ Danz saw numbers spike on his YouTube channel, while Eric Lopez, AKA DJ Ericnem, began to make budots music himself around that time. Like Tuna, Lopez’s entry to electronic music came through dance. “I used to make music for my dance group, and then ended up learning how to DJ,” he recalls. ”I ended up catching a wave of budots, and saw that it’s actually really good for dancing and that people loved the music, so I started making budots myself.”

Ever since, the genre’s popularity has surged, first online and boosted by the advent of TikTok – where its pre-existing dance style and attention-grabbing sound proved potent for its algorithms. Its success spanned across both borders and class, so much so that even US pop princess Olivia Rodrigo jumped on the TikTok trend. Meanwhile, during the pandemic, DJ Love would go on Facebook Live from his internet café office/studio, streaming regular marathon budots sessions, lit by primary-coloured LED lights and lasers, gaining a captive audience in the process.

Similarly to how hip hop infiltrated mainstream US culture, budots was no longer a sound from the slums. “It became a shared community experience,” says Tuna. “Where people would gather round, do karaoke, bust out tuba [Filipino coconut wine], and then people would just dance and have fun. Then, [as the popularity grew], I tried to make it palatable to more people and the middle-class by making pop edits.”

Read this next: Inside Budots, the Pinoy dance music phenomenon that took the Philippines by storm

Bootlegging and sampling has been a big part of budots since its early iterations, with samples often spliced from radio, television shows, or viral videos, providing playful Visayan cultural references in the tracks. But within that phenomenon has come its own evolution, with producers re-recording what would otherwise be copyrighted material, and creating something new in the process.

“Budots is very based in remixes, edits and samples,” explains David Zhou, co-founder of Eastern Margins. “But producers are getting around restrictions by recreating samples themselves – all the samples are created by them talking. It’s a really creative way of evolving the sound.”

And now, beyond the streets and social media, the sound has increasingly infiltrated the Philippines’ club scene, leading to a Manila Community Radio x Boiler Room stream in 2023, headlined by Tuna himself. Backed by dancers swaying side-to-side, and taking his moments to get down low himself, the stream was a chance to introduce the genre’s tiw tiw whistles to global electronic music lovers – to date, it has nearly half a million views on YouTube.

Its growth can also be seen in the spread of the scene’s visual language. Along with the dramatic music, budots without fail comes alongside bold imagery. Look up any music video, and the screen will transform into a nostalgic goulash of Word Art type, MySpace era collage, and PowerPoint golden age animations. It’s hardly highbrow, but it’s maximalist and fun, and co-opting that style, the poster that promoted the Manila Community Radio x Boiler Room is a wild splash of pink and yellow, with Pegasus imagery, a Jesus figure giving a hug, and font plucked straight out of the early days of the internet.

Lacanilao himself has worked with graphics for a lot of his life, and worked out early on that attention grabbing visuals translated to success online. “I used to be a graphic designer, and I made tarpaulin layouts and big banners for birthday celebrations in the Philippines,” he explains. “So [my style] comes from that.”

With its success, has seen the building of something of a collaborative, increasingly organised scene. DJ Danz, DJ Ericnem and DJ Love sought each other out after hearing their productions, which has seen them dubbed ‘The Budots Three’ – a winking reference to Detroit techno originators The Belleville Three, while Lacanilao has been helping Lopez navigate YouTube and the digital landscape. Between them, the trio have racked up several millions of views on their tracks and streams.

And around two decades since DJ Love first started playing around on FL Studio, the genre is continuing to evolve. “I’m proud,” says Lopez. “We used to get ridiculed for doing budots. People used to look down on it, but I’m okay with it because I do other styles – haters zone in on the budots, but we aren’t limited by genre. There’s a lot of variety in budots, and I’ve made music in a lot of them.”

Labelling the trio’s music in the present day simply as budots is ultimately reductive, and the 13 tracks on ‘3-Hit Combo!’ act as an introduction to where the genre is at sonically. There’s Bomb Tek budots, which switches up more spacious, syncopated rhythms for four-to-the-floor thumps, perhaps best heard in DJ Danz’s ‘Hit The Button’. On the other end of the spectrum, DJ Ericnem’s ‘Are You Ready’ is a ravey, almost heads-down heater that could shake any warehouse from Manila to London.

“It’s my dream to spread the sound of DJ Danz and DJ Ericnem,” says Tuna. “I feel that they are better than me technically – I just did it before them, but they are ahead now. Working together on something like this is a dream.”

Attitudes have shifted towards budots, and it’s no longer a genre that more privileged heads in Manila turn their noses up at, just as ghettotech is in the USA, or hardstyle and gabber in Europe, or even happy hardcore and grime in the UK, which all had origins as working-class genres. But it also reflects a growing pride in homegrown cultures, in a region where Western music and culture has historically been placed on a pedestal.

“It’s an interesting phenomenon that’s replicated across a number of different Southeast Asian music genres, like funkot from Indonesia, and vinahouse in Vietnam,” says Zhou. “All of those have different colonial histories, but it speaks to how when something gets international recognition it will be seen in a different light in a domestic context. I think the budots scene is quite well established, so in a way people like, Sherwin, Danz and Eric are ready to receive the attention that they have been given.”

And for The Budots Three, they are focused on continuing to make their music and get hips swaying, just as they always have. “So many people are making budots now, and people riding the budots trend,” says Lacanilao. “As long as budots doesn’t get discriminated against, we’re happy.”

“It’s really about inspiring people to do remixes, or people to play at parties,” adds Lopez. “The main purpose is to make people happy – and to make people dance.”

'Budots World: 3-Hit Combo!' is out now via Eastern Margins, buy it here.