Features

Features

How Nusasonic by Goethe-Institut is moulding more progressive perspectives through cross-cultural experiences

The regional sound art & experimental music collective talks about the importance of socio-political history & growing together through dispute and determination

Aural stimulation isn’t one that Nusasonic takes lightly. In fact, every step the multi-disciplinary regional music collective takes are as careful and as introspective as their practice. With co-founding collectives, Yes No Klub (Yogyakarta), WSK Festival of the Recently Possible (Manila), Playfreely/BlackKaji (Singapore), and CTM Festival for Adventurous Music & Art (Berlin), one can only imagine the sheer amount of hard work and dedication that goes into their projects.

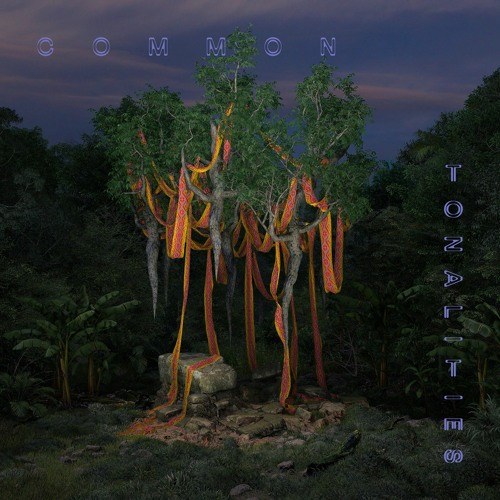

Catapulted by an idea that was pitched by co-founder, Merv Espina to the Goethe-Institut Indonesia’s director in 2017, Nusasonic has since been showcasing experimental music and sound art through festivals, residencies, collaborations, lectures, and satellite events around the globe, along with their recent 20-track compilation, Common Tonalities.

From dealing with different personalities across multiple time zones and screening countless talents to often tackling discourses on socio-political and cultural issues that define their beliefs and practices, we set out to learn more about their earliest days coming together, their latest release, and how the current climate has thrusted them into greater albeit challenging heights.

Could you walk us through your origins as Nusasonic? What drove you to establish a region-spanning collective?

Wok The Rock: The idea emerged in 2017 from a proposal by Merv Espina to the Goethe-Institut Indonesia's Director of arts and culture to develop a network and exchange of ideas for sound art and experimental music practice in Southeast Asia and Europe.

Goethe-Institut Indonesien then invited CTM Festival and Rabih Beaini, a musician and producer from Berlin to do research in Indonesia, the Philippines, and Singapore and happily work together with music collectives from Southeast Asia: Yes No Klub from Yogyakarta, Indonesia, Playfreely/Blackkaji from Singapore, and WSK Festival from Manila, The Philippines based on CTM Festival’s preference.

Read this next: Inside Budots, the Pinoy dance music phenomenon that took the Philippines by storm

Merv: The seed of the idea that would become Nusasonic actually came from Singaporean curator and dramaturg Tang Fu Kuen. There are quite a few important initiatives in the region -- ranging from labels, platforms, festivals, etc -- that have been exploring interesting aspects and directions in sound and music. Yet, there has not been a lot of sustained collaboration, debate, and criticality. A lot of the same conversations were being had over and over again. A lot of projects seem repetitive. So we wanted to address this somehow and push the conversation forward.

Goethe-Institut has had a long engagement in the Southeast Asian region, especially with projects that explore new tangents of practice. Their series of experimental film and video art workshops were quite instrumental in the 80s and 90s, and was an important juncture in the practice of future media artists and filmmakers that have become stalwarts in their respective contexts. In the Philippines, people like Lav Diaz, Raymond Red, Roxlee, Tad Ermitaño, and Ditsi Carolino, all came through those workshops. So maybe a German-Southeast Asian collaboration that could explore intersections of new, experimental electronic music, sound art, and unique aural cultures and traditions would be something that could also spark or usher in new ways of thinking and practice that would benefit the practitioners and push the dialogues forward in various contexts.

Read this next: Metro Manila welcomes "new normal" with no restrictions on venue capacity

The Goethe-Institut in Jakarta is the headquarters for all the Goethe-Institut offices in the Southeast Asia, Australia, and New Zealand region, so in 2017, Fu Kuen introduced me to Heinrich Blömeke, the director at that time, to see if this could be something they would be interested to support. We had a few meetings, proposed and lobbied for it, but we didn’t really write a proposal.

After CTM Festival’s research trip to Yogyakarta, Manila and Singapore (2017) with the invitation from Goethe-Institut Indonesien, Jan Rohlf of CTM Festival wrote a long report and recommendation for Goethe-Institut and a lot of the heavy lifting in the early months before the partnership with Goethe Institut Indonesien came through.

Maya and Anna Maria Strauß (former head of cultural programmes of Goethe-Institut Jakarta, succeeded by Ingo Schöningh after her tenure), are the representatives for Goethe-Institut. Goethe-Institut doesn’t contribute actively in the curatorial decisions and chose to contribute more in their suitable and natural expertise and resources: organisation and financial.

Jan would later be joined by Taïca Resplansky for the CTM representation in the Nusasonic working group - who’s in charge of the editorial. CTM incorporated Nusasonic programming into their 2019 festival for the first introduction in Germany. Wok The Rock from Yes No Klub, Yogyakarta, hosted the first Nusasonic event, a 10 days festival in 2018. Yuen Chee Wai and Cheryl Ong are the main representatives for Playfreely/BlackKaji Singapore, and they programmed a special Nusasonic edition in 2019. The Singapore event was soon followed by incorporating Nusasonic programming into WSK 2019. From WSK in Manila, it was musical chairs between Tengal Drilon, Joee Mejias, Dale Bazar and myself to take the lead on Nusasonic matters since 2018. Then to complete the Nusasonic team, there Zefan in Jakarta, and a full-time museum worker at Museum MACAN, who handles Nusasonic’s social media.

Read this next: 5 recent Filipino releases you might have slept on

Could you tell us more about Common Tonalities? What it is, what you aim it to be and what the audience can get out of it?

Merv: Being “sintunado”, or being out of tune, is really a case for context. Not a lot of people realise that the standardisation of certain notes have really been quite recent, and what is followed now is quite Western imposition, that’s also ingrained into audio production software. We’ve been conditioned to hear things a certain way, and things that don’t follow certain patterns we’re conditioned to would seem off or weird or out of tune.

But there are worlds in between A and A#. Even in the Western art music tradition, Mozart, Beethoven and Verdi created their masterpieces in A as 432 Hz, not in the modern A as 422 Hz reference standard. In many places in Southeast Asia, there’s many systems and traditions of tuning.

Common Tonalities is a project that explored Southeast Asian tunings systems and scales. It was mainly a series of workshops led by musician-scholar Khyam Allami that led to commissioned works for a compilation album with 20 new works from 20 artists from Southeast Asia and the diaspora. The selection process was hard. We had an open call and nudged a few people, aspiring for representatives from most, if not all, of the geopolitical Southeast countries (ASEAN).

Prior to the workshops, we had an online panel discussion, Tuning in/Sounding Off, with Khyam Allami, Tan Shzr Ee, Ros Phoasavadi, and senior Southeast Asian ethnomusicologist Joseph Peters.

As for more context, I think Khyam Allami said this best in his introduction for the Nusasonic booklet, as well as the individual artists in their individual notes for their compositions.

Read this next: 48 hours in Metro Manila: a culture-keen clubber’s guide

How do you see Nusasonic growing in the future? What are you gearing towards to?

Chee Wai: I think one of the main goals is to organically bring the music scenes closer. We are cognisant of the fact that funding support for Nusasonic by Goethe-Institut is finite, and that makes it even more urgent for us to form these informal links between ourselves to support the networks, be it through mutual aid or acts of solidarity. Through the years of working together, it has also revealed asymmetries of funding availability and sensitised us all to proactively support one another in times of need. So these are probably some kinds of intangible organic developments that has evolved, and will further evolve informally of this Nusasonic network. Of course, this does not and should not pertain to only the collective of four4 festivals/initiatives of Nusasonic, as we had also actively broadened our inclusions of many other collectives, partners and initiatives within the region.

Now that the scene across the globe is slightly opening up (thankfully, we are enjoying a bit of it here in Manila), how do you see Nusasonic getting involved? How do you envision this creative, musical scene growing?

Merv: I always think of scenes in the plural, in any given location. Metro Manila has quite a few, not all of them intersect, much else for Southeast Asia and Europe. Nusasonic can be seen as an attempt at trying to address this, by making some intersections that would hopefully translate to relationships and ideas that would last beyond festival and residency cycles both ways.

Read this next: How similarobjects is using music to amplify protests in the Philippines

With Nusasonic at the forefront of redefining what artistic sound discipline means in the cross-cultural diaspora, one can hope that collectives such as them would continue to be amplified, to progress and thrive across global scenes — and always with such resolute conviction.