Features

Features

“For all the misfits in the world”: Peter Hook shares why The Haçienda was and still is ahead of its time

The venue's former co-owner looks back on a space that turned DJs into demigods, the importance of inclusion & the shared euphoria that made The Haçienda a global cultural force

There are clubs, and then there are places that rewire culture. The Haçienda was, and remains, firmly the latter.

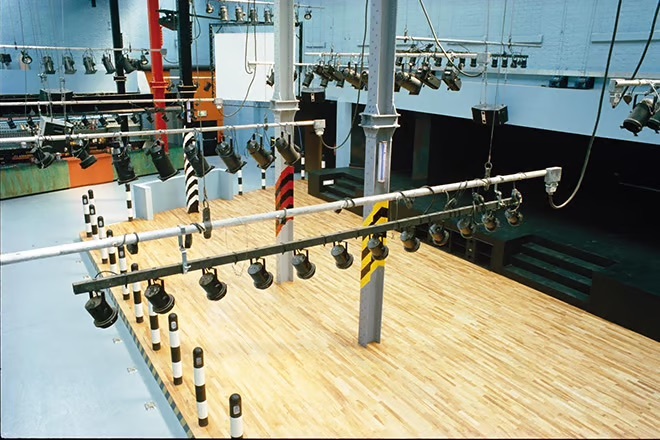

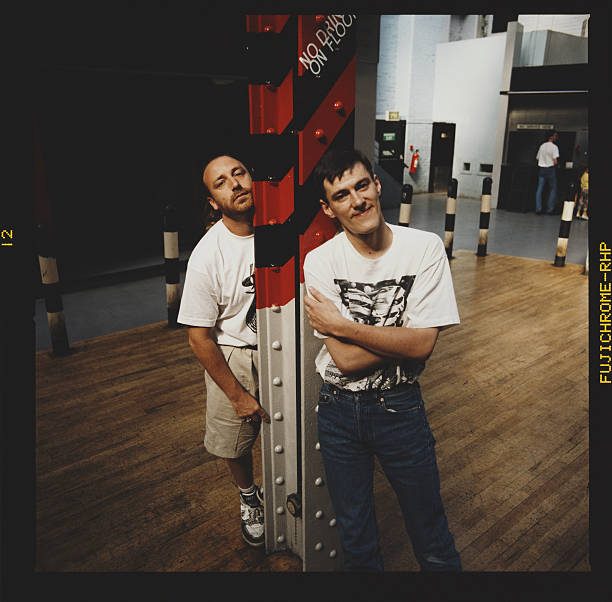

When the venue first opened its doors on Whitworth Street in Manchester in May 1982—just several months before Mixmag published its first issue—few could have predicted that a former yacht showroom would become one of the most influential cultural sites of the late 20th century. Yet even now, decades after the original building closed in 1997, The Haçienda’s influence continues to shape how club culture looks, sounds and connects globally.

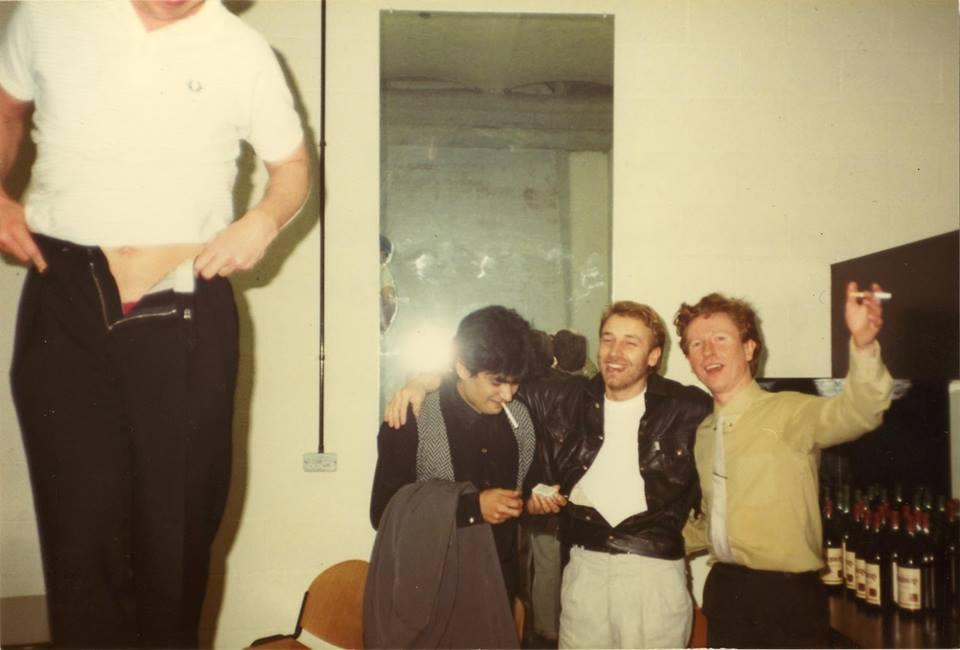

Founded and driven by the restless vision of Tony Wilson, Rob Gretton and Alan Erasmus of Factory Records plus the band New Order, The Haçienda (FAC51) took cues from New York’s expansive club ecosystem such as the likes of Studio54, while remaining fiercely Mancunian in spirit.

Its industrial interior by Ben Kelly, paired with Peter Saville’s graphic language, made the space feel radical, even confrontational at times. But sound was always the core.

Tony Wilson suggests a sense of cultural responsibility when asked in a television interview “Why bother building the Haçienda?”. Rather than talking in business terms, he frames the venue as something Manchester needed for youth culture to exist and for the city to take itself seriously on a global stage: “It’s necessary for every period to build its cathedrals, it’s necessary for any youth culture to have a place, a sense of place, and Manchester had never had one for many years. We find ourselves in a financial situation where we can do something about it, and thirdly it’s necessary for a city like Manchester, which is an important city and has been important to music to have the facilities that New York and Paris have and to not have them would be a disgrace.”

From the beginning, the club resisted being boxed into a single genre. Early bookings ranged from post-punk and live bands to hip hop and electronic experimentation, with artists such as Run-DMC, Gil Scott-Heron and Madonna (whose first performance outside New York took place there) passing through its doors.

Read this next: The Haçienda like they always saw it: New photobook documents the iconic Manchester venue

That openness made The Haçienda a cultural meeting point. American DJs found international recognition there. British selectors became pop-cultural figures. Students, artists and outsiders mingled freely. The Chemical Brothers famously met at the club while at university; Sasha was said to have left school early so he could spend more time dancing there. Underworld, 808 State and countless others absorbed its atmosphere and carried it forward.

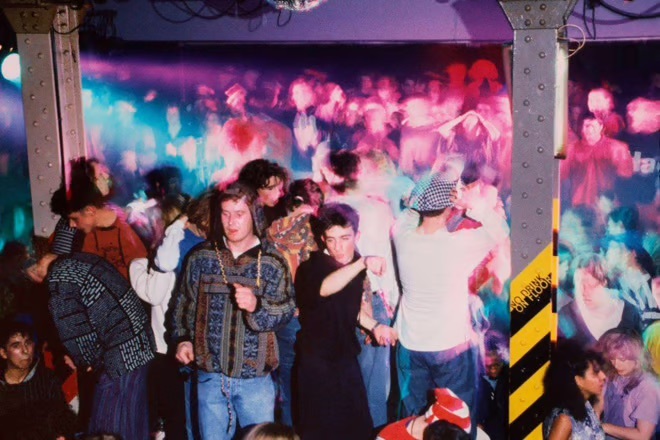

By the mid-to-late 1980s, The Haçienda had become synonymous with house music and the Second Summer of Love. Nights like Nude, helmed by Mike Pickering and later Graeme Park, transformed DJ culture in the UK. Clubbers travelled from across the North (Leeds, Nottingham, Blackpool, Middlesbrough) queueing for hours just to experience it.

As Dave Seaman documented in Mixmag in 1989, these crowds treated the club and its sonic purveyors as “demi-gods”, responding viscerally to records like ‘Strings of Life’, ‘Carino’ and ‘I Need Somebody’. The dancefloor became a site of shared emotional release.

This period also catalysed what would later be labelled the Madchester movement; a collision of acid house, indie guitar bands, psychedelic influences and a new hedonism that redefined British youth culture. The Happy Mondays, The Stone Roses and New Order themselves drew energy from the club’s ecosystem.

Read this next: 6 of the best documentaries exploring the highs & lows of acid house culture

Though The Haçienda may not have invented dance music per se, it provided the conditions for rave culture to take root, scale up and export itself worldwide.

When the original venue eventually closed, its myth only expanded. Documentaries, books and films such as 24 Hour Party People and Peter Hook’s How Not To Run A Club cemented its status as the site of one of Britain’s most significant cultural revolutions since punk.

Yet The Haçienda never fossilised. Instead, it evolved into more than a brand: a living framework for events, collaborations and reinterpretations. From global club nights to the 70-piece orchestra project Haçienda Classical, which reached millions worldwide via livestream and is celebrating its 10th anniversary this year, it has continued to connect generations through a shared musical language.

That evolution is key to understanding why The Haçienda’s presence in Asia now feels timely rather than retrospective. Across the region, British music from the late 80s and 90s (particularly from Manchester) has never faded into pure nostalgia, and still circulates through karaoke bars, record shops, DJ sets and online communities.

The cathedral may have closed its original doors, but the congregation is still gathering.

Read this next: Suddi Raval recalls the revolutionary times of acid house in the UK

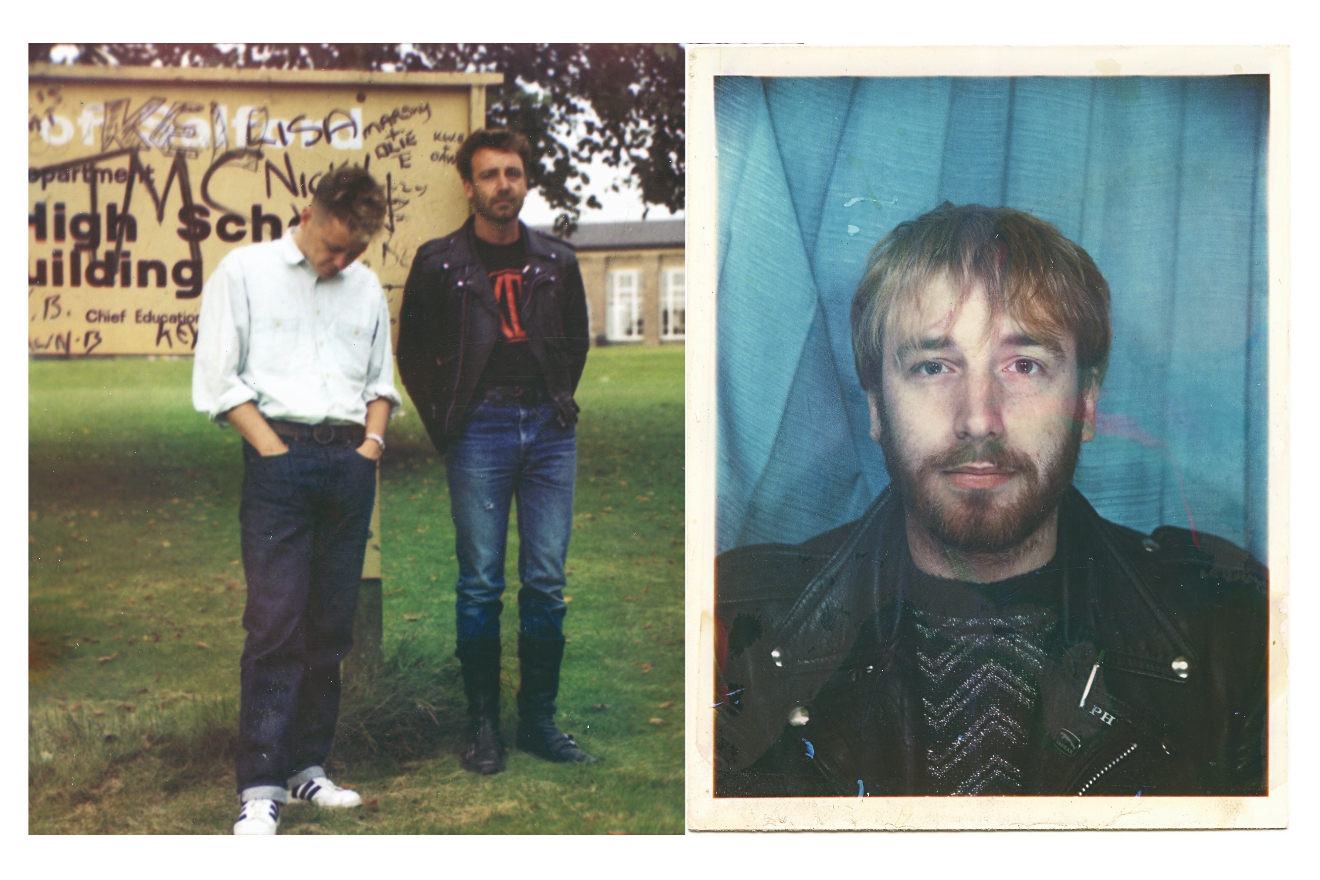

It goes without saying that Peter Hook’s presence in any line-up that The Haçienda presents carries particular weight.

As a founding member of New Order and original co-owner of The Haçienda, he remains one of the few people able to speak not just about what the club became, but why it was built in the first place…and why its ethos still matters now.

What happens when a club built for misfits becomes a global reference point? We’ll let the man tell you himself.

The Haçienda could be said to have been born at a time when British music culture was still evolving, almost being written in real time. Now the name is turning up around the world and in Asia, do you see it as something being carried outward from Manchester, or something that keeps changing wherever it lands?

That’s an interesting question. The key thing is what I’m celebrating. When we began the club in 1982, it was for all the misfits in the world, like me. So that we had somewhere to go, somewhere to rally around, to be with other people who were alike, who were outsiders, where we had something to share.

Now, that ethos has not changed. The music played went through many stages. It was open for 15 years, which is quite a long time in nightclub terms, and it was a huge influence on many people, culturally and musically, around the world.

So the thing is, I’m putting all of it out there. Sometimes we focus on parts of it, like with Haçienda Classical, where you’re going to a slightly different audience. With club nights, you’re going to a more, shall we say, purist, music-focused audience.

For what The Haçienda meant to the people of Manchester, I’m trying to fly it all around the world.

Manchester music from the late ’80s and ’90s is still hugely popular across Southeast Asia—clubs, karaoke bars, even just in headphones. Why do you think that emotional connection has travelled so far?

New Order, in particular, worked very hard at getting the message across the world. We did it very much on our own terms, but the thing is, we wrote songs that were suitable for radio, so you managed to get your music played all around the world.

New Order never came to Thailand, although I’ve DJed there. And funnily enough, The Haçienda is actually more relevant now—culturally, musically, and even from a fashion point of view—than it was years ago. The message is still going round.

What delights me is that our audience is getting younger and younger, because there’s still an appreciation for the music, which is, in fact, timeless.

The Haçienda was defined by a collective spirit—crowds, DJs, artists all played a role in shaping it. Do you see that same drive in today’s underground scenes, in Manchester or elsewhere, or have the dynamics shifted?

The Haçienda was different. It was funded entirely by Joy Division and New Order. The reason we did it was because we went to America and saw a completely different aesthetic in clubs—a different welcome and a different attitude to music. It was inclusive. Everything was inclusive.

In England, it was very backward. You could only get into a nightclub wearing a suit, like a businessman. The music was very pop-oriented, chart-oriented. There was nothing really special or forward-thinking about it.

So The Haçienda was opened on New Order and Factory Records’ terms: all-inclusive. “We’ll try anything. If you can give us a good pitch, we’ll put you on.” But it has to be said that musicians are not great businessmen, and idealism is not a great way of doing business. Without New Order and Joy Division’s money, and our continued success selling records, The Haçienda wouldn’t have stayed open as long as it did. To my knowledge, there is no other club in the world before or since that was founded by a band purely for the good of the people of its city.

It was very un-passive, very unusual, right from the word go. And ultimately, our lack of business acumen is what brought it down. We weren’t interested in running a club for money.

The Haçienda wasn’t successful originally. For the first four or five years it was mainly a live music venue. Mike Pickering, who was our booker and later a very well-known DJ, was very forward-thinking—American music, Detroit, Chicago—but nobody was interested at first.

It was only when acid house came along, with the Ibiza connection, that we were able to tap into it and promote the music we’d already been pushing for years. I see flyers from 1983 and ’84 with the same names that were huge in ’88, ’89, and later in the ’90s.

So The Haçienda was ahead of its time.

Would you say the music itself was the main reason The Haçienda became so influential, even if it wasn’t financially successful?

Yes. It was the belief in promoting different kinds of music, fashion, culture, and life—being inclusive. As punks in Manchester, we were not welcome anywhere. Literally nowhere. So that’s why we started the club.

Why did it grow to have such worldwide influence? Pure blind luck. It wasn’t planned. We were flying by the seat of our pants and caught onto important movements at the right time.

Once acid house hit, it caused a monumental cultural shift in England. The Haçienda, Shoom, Heaven in London—they’ve been written about endlessly. And yes, the drug side came with it, which I’m ashamed of. It was naïve and stupid, but what I’m happy about is that the music outlasted everything.

The Haçienda influenced artists like The Chemical Brothers, Underworld, and 808 State…

Yeah, The Chemical Brothers met at The Haçienda. It was very flattering. New Order and 808 State toured America together—we played to 30,000 people. We were far more successful there than in England. So it’s lovely to start that connection again. There is no greater feeling than unity.

The world is terrifying at the moment, and music is one of the few neutral places where people can come together, forget their problems, and celebrate life. That’s more important now than ever.

Do clubs still have the power to shape artists today?

Tony Wilson used to say that music and culture are like a wheel, you have to keep it turning, or it stagnates. Clubs are vital for giving new artists a chance. Social media is great, but you still need clubs. DJing is an art. Learning how to move people, excite them…that can only happen in real spaces, with real people.

What kind of feeling do you want to leave on the dancefloor?

I don’t pre-record sets. I make it up as I go along, make mistakes, but I’ve got a big smile on my face. If people leave smiling, what more can you ask for? DJing still terrifies me more than playing in a band. Some audiences can be antagonistic, but it’s all about learning. I still feel blessed to be doing this. Reading a crowd in a foreign country is a challenge, but we’re hoping to make old fans happy and create some new ones.

After all these years, what still excites you about bringing The Haçienda and your ethos somewhere new?

Every gig still excites me like it did in 1976. I’m very lucky to do a job I love. Without people, we’d be nothing. I was blagging it at the start, and I’m still blagging it now. And I love that idea—that someone can think, “If he can do it, I can do it.”

Without hope, what the hell have we got?

Amira Waworuntu is Mixmag Asia’s Managing Editor, follow her on Instagram.

Cut through the noise—sign up for our weekly Scene Report or follow us on Instagram to get the latest from Asia and the Asian diaspora!