Interviews

Interviews

Dear mum, I’m going to write my PhD on Hong Kong’s rave culture

Hong Kong-based artist Mengzy is documenting the 90s rave scene in the city in a forthcoming research paper

Without diving into the political history behind Hong Kong’s colonial era, although a chunk of it is certainly relevant for today’s topic, we’re going to saw straight to the bones of how and why a mixed-Asian, third-culture kid, student-turned-DJ decided to develop a thesis on rave culture from Hong Kong’s past and present.

Her name is Li Meng de Bakker, but you’re more likely to recognise her as Mengzy from her gig flyers, her local radio show RTHK Radio 3 or her most recent set for Mixmag Asia Radio. The half-Dutch, half-Singaporean-Chinese DJ is a no-nonsense music aficionado, more specifically, a bass hunter and is an unassuming DJ talent with a serious thirst for dance floor obscurities. For her Bachelor's degree, she majored in Comparative Literature with a double minor in music and journalism. She also bagged a Masters in Music under her belt from the Chinese University of Hong Kong. DJing only came to her through her time as a student, and of course, through her curiosity. "Hong Kong is so exciting to experience as a city, especially coming from a suburban upbringing," she said to Mixmag Asia. "And I’m fascinated by dance music history which obviously quickly led to me being infatuated by rave culture. So, here we are.”

But when I ask her to put personal musical ambitions aside, we’re left with nothing but her curiosity and I quickly learn that this vast space filled with knowledge-seeking cerebral nodes lights up whenever the word rave is thrown around.

Why rave? What about rave history and culture, and more so, the rave culture and history of an ex-colonial dot on the map called Hong Kong? We hardly experience it like we used to, but maybe that’s why her curiosity was so aroused. But, really, it doesn’t actually matter why she’s interested in it, the bottom line is that she is, and profoundly so, and I found it rather fascinating that a person is willing to shelf four years of their primal youth to research and write a thesis on Hong Kong’s rave culture. It’s refreshing, and rather needed, particularly for a city that prefers to sweep culture under the rug (unless it turns dollar signs), and that’s why we sat down to talk about it.

“Firstly, what does rave mean to you?”, I ask right off the bat. Slightly stumped, as she’s literally in the middle of her research trying to understand Hong Kong’s rave journey from its Atlantic roots, she answers, “Temporary autonomous zones”. I knew our conversation was off to a deep start from here on, but I also knew that I had to tread carefully with my questions as her answers would mostly stem from the research that is bound by her commitment to the University of Hong Kong.

She started out with pure fascination with the concept of rave, its culture, its rise and demise, its evolution and I guess in terms of our focus in conversation, the globalisation of it. It just so happens that Mengzy was in Hong Kong already to do her Bachelor's and Master's degrees and she didn’t want to leave, and the University of Hong Kong has a reputable Music Department. By this point of realisation, it didn’t take long for her to scout a potential professor to agree to supervise her research topic. But the primary reason for choosing to research about rave in Hong Kong was practical she says, “because I’ve made Hong Kong my home. I first moved here in 2009 to do my Bachelor’s at HKU and have been here ever since. But there’s also the research reasons — there’s a gap in the literature that my research hopes to fill. There’s been lots written about rave in the UK and US, but not Hong Kong."

Although that particular professor had previous interests in Japan’s underground alternative scene, Mengzy saw that as a convenient parallel to approach him with her ideas. And her ideas were confidently substantiated — not only does there exist a vast range of rave-related literature, but Hong Kong itself has a unique history with the importation and its own adaptation of British big-room-dance-floor antics for the rebellious at heart.

So, Mengzy secured the meeting with the professor she hoped to be supervised by, and then she had to convince the University with a solid proposal that explained the research, why her topic was interesting and how it would contribute to the University's archive of literature. Upon saying yes, she would then have to go through 18 months of candidature, which was "more or less like a probation period, by the end of which I then have to submit a real and formal proposal after narrowing down the research topic. After which, if you are officially confirmed, you are then allowed to continue to finish the PhD and write the thesis”.

“Kudos to my supervisor, he and the faculty were very really receptive and supportive from the beginning. The early application went in well, and they said two PhD students are accepted per year in the Music Department. I was the musicology submission, the other guy was composition.”

The deadline for her thesis is April 2022, and despite me thinking that she’s got plenty of time on her hands, she’s actually wildly nervous and stressed out, but she was comfortable enough to let me probe into at least the surface of her research as I was now curious about what tools she would use to develop her paper. “In-depth interviews with DJs, promoters, rave literature and autoethnography. It’s certainly a challenge, especially the latter part, as it's biased observations that I have to declare as bias in my research.” Although her research is sacred at this point, she was kind enough to let me indulge in a few of the key works that opened her mind and directed her thesis quite profoundly, at least up until now.

She starts out with Hakim Bey’s Temporary Autonomous Zone, the same phrase she used to describe what rave meant to her. “Hakim explores the more radical side of rave culture”, she says. “Then there’s Sarah Thornton’s ‘Subcultural Capital’ which builds on Bourdieu’s cultural capital and was developed in her seminal book ‘Club Cultures’. Then there are foundational works like Dick Hebdige’s ‘Subculture: The Meaning of Style', which albeit outdated, has some fundamental theories. And then there’s one of the first collections on rave culture, specifically from Manchester and around Britain, ‘Rave Off: Politics and Deviance in Contemporary Youth Culture (edited by Steve Redhead)'.”

Reading aside, to understand Hong Kong’s rich late-night history, Mengzy reached out to some of the key players of the early and pioneering rave days. “My supervisor pointed out to me that the testimonies and oral histories I’m collecting are parts of Hong Kong’s cultural memory that could be lost with time, so that’s incredibly humbling.” It must certainly also be inspiring, and Mengzy was nothing but grateful, while still cautious when she started to reveal a few names and moments that have been part of her research journey, and it includes DJs like Blackjack aka Simon Birch, Lee Burridge, Joel Lai and Frankie Lam, amongst many others she didn’t name yet or hasn’t spoken to, who were the foundation of Hong Kong’s electronic music scene. Lee, the founder of today’s popular playa house imprint All Day I Dream, was known as a true champion of breakbeat — he was accompanied throughout the 90s by Hong Kong-raised DJ Christian Berentson, during when they both helmed the booth of Neptunes in Wan Chai. Neptune was the after-hours spot of Hong Kong, and Wan Chai was the red light hub of Hong Kong Island.

The things that happened at Neptune were seeded from the disco scene that was birthed by Canton Disco on the other side of the harbour in Tsim Sha Tsui — Canton Disco was the Orientalist answer to New York’s Studio 54. But the real essence of how we got to the rave stems from the story of dance music. She says: "Rave was what took it out of a subcultural context and made it mainstream… The UK rave scene was the first time where it was huge, with massive crowds. That wasn’t necessarily happening in the US which was adamantly underground and mostly populated by black and gay communities. But in the UK it blew up and became where football hooligans were out and taking pills and then hanging out with black people for the first time. That legacy is so massive, it really popularised dance music worldwide.”

Listen to Andrew Bull’s live recording from Disco Disco, one of Lan Kwai Fong’s first dance floors, and the predecessor of the current manifestation of the space, Volar.

And in the meantime, Hong Kong was through the prime of it’s colonial era. “The guys in the rave scene over there in the UK brought that over here as expatriates, and then eventually continued as students would return from University back to Hong Kong filled with all this knowledge and experience.”

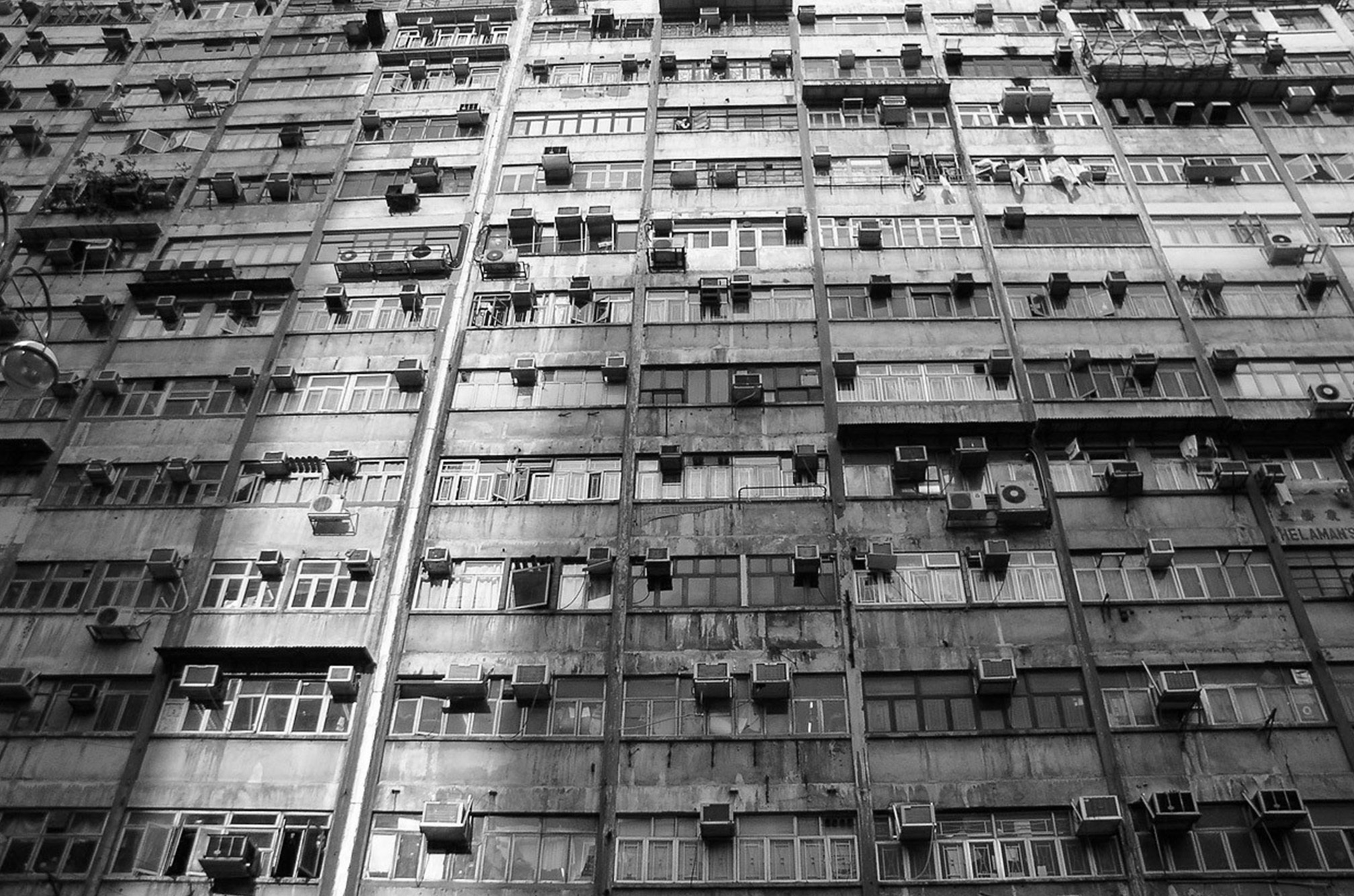

Hong Kong’s colonial history has a deep foot in the story of rave, “and so does Canada”, according to Mengzy. The scene in Hong Kong grew quickly, quality house music was being played at the more popular bars and clubs and DJs were hauling records back and forth. It was an exciting time that paved the way for really large events (large by Hong Kong standards).

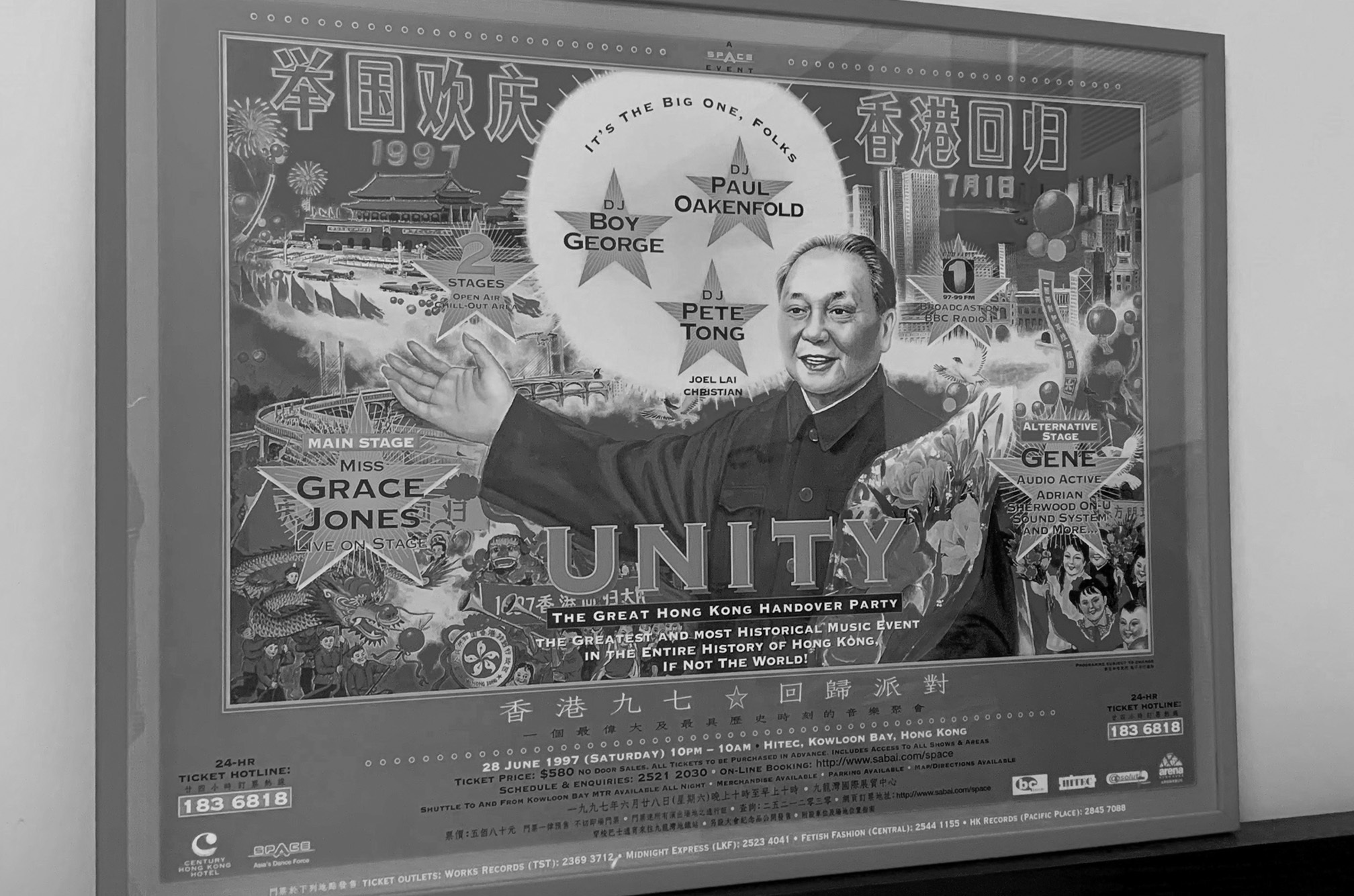

One of the most prolific and memorable raves that Mengzy cites from her research is Unity - The Great Hong Kong Handover Party in 1997 put together by the legendary promoter, and now Shanghai-based DJ (DJ El Toro), Andrew Bull, who was also responsible for the programming at the aforementioned Canton Disco. It was a 12-hour romper that featured Boy George, Grace Jones, Pete Tong and Paul Oakenfold for 12,000 Hong Kong ravers. It was a historic rave, not just for the city, but even for the artists, who were all British, while Grace Jones shared her colonial roots via Jamaica with fellow Hong Kongers. And on an absolutely irrelevant but gossip-worthy side note, Grace and George got into what was close to a punch-up on stage, as they were both fighting for more limelight. Their party didn’t stop that night though, as Andrew Bull, Grace Jones and company headed over to Bali to continue the celebration for the next ten days.

Avex Trax even released a mix CD under the Unity brand that featured classic hits from the likes of Armand van Helden, DJ Quicksilver and Ultra Nate. It shouldn’t surprise you that Mengzy managed to source a second-hand off the Caroussell app from a seller in Singapore, which her brother had to arrange for her.

But you don’t have to order the CD, Pete Tong broadcasted the live recordings on his Essential Mix just a few days after the party.

Andrew Bull also takes claim for throwing the first rave in Hong Kong. I reached out to the man who celebrates his 50th year since spinning his first record in Hong Kong, and his story says it all. “It was the first rave in Hong Kong put together by me and Liam Fitzpatrick, held in a now-demolished huge shop house/warehouse in the Westen District," he told us. "It was a trendy clothing store during the day called Man & Earth run by one of the founders of Esprit, Sandy Hui. He lived on the roof but let me and Liam run the rave every Saturday on an otherwise unused floor. It was unlicensed and vaguely illegal and on top of that, we had no relationship with the police or local 'mafiosi'. Miraculously we lasted for ten Saturdays with hundreds through the door every time. On the 10th week, the police arrived to shut us down via the front door whilst simultaneously the local triads broke in through the backdoor to muscle in on the action. Needless to say, we told both invaders to f*** off and disappeared into the night”.

Mengzy elaborates on her surprise about Hong Kong’s prolific dance during its rave heyday. "Multiple A-list DJs would frequent Hong Kong every month, playing to anywhere from 5,000 to 10,000 people.” This city saw most major entities in dance music come through to play records — Basement Jaxx, Timo Maas, Seb Fontaine, Max Graham, Carl Cox, John Digweed, Sasha, Gatecrasher, Global Underground… to name but a few.

Our conversation eventually touches on some of her content pillars of research, and we explore the reasons and facets of how Hong Kong’s rave scene shaped itself — apart from the cultural trade benefits of the city’s colonial period, Hong Kong had a few other difficulties when it came to sustaining its underground dance movement.

This is how Mengzy and I rapidly broke down Hong Kong’s 90’s rave scene:

Foremost, there’s the triad (the Chinese equivalent to the Italian mafia) connection and the battle they fought against promoters over the control of narcotics. Pills were the choice of poison for most ravers, but the gangs were trying to push their own supply of k through. The two chemical compounds were the preferred choice, but with two very different effects on Hong Kong’s rave society. E kept the kids up all night, full of floating energy. K, on the other hand, created an atmosphere of zombies, with kids slouching against the sidewalls of the rave hall, totally ungrounded. It wasn’t long before the authorities were cracking down on the parties, increasing their presence through sniffer dogs, mobile temporary jails, infiltrating with undercovers and conducting lengthy security checks.

The local media and authorities made it a point to highlight the drug culture associated with raves, citing health warnings and statistics of substance abuse. But they mostly left out the roots of it — the causality of the rave scene stems from a combination of expressionism and escapism, the latter of which was only ever negatively highlighted. There was one media outlet, however, that embraced and glorified the culture and the creative souls that basked in it, and it was a staple read for Hong Kong’s nocturnal youth — Absolute Magazine.

I used to have a stack of issues that I collected in my mid-to-late teens, but 20 years of hoarding was all I could get out of my patient mother. However, Mengzy managed to hunt down a substantial collection through Simon Birch (DJ Blackjack) and it took her straight to the core of the real substance of Hong Kong’s dance, rave and club scenes — the counter-culture idea of a media platform supporting an underground movement made it both intrinsic to the city, but it was certainly not an easy business to sustain. The magazine’s demise was pretty much parallel to the source of its content, so as the parties slowed down, so did Absolute’s effort at chronicling Hong Kong’s nightlife.

Too many raves were being shut down and the kids were growing up. It’s important to note that Hong Kong’s party population is rather minuscule compared to other international cities. In fact, it declined heavily after 1997. The basic economics of HK’s rave culture and business was at peril, and then came SARS, which put a stop to most things for most people for just under a year. “Another claim made by one of my subjects, which I’m still researching, is that Hong Kong’s economy was in bad shape around and after SARS, which pushed owners of alternative venues to open up their spaces to promoters as they needed the business.” When this happened, the party scene was quickly diluted, the scene evolved from big room antics to intimate hole-in-the-wall spaces. The few and far larger events still happened with less frequency, but they shifted to more privately run spaces like hotel ballrooms, where police had less control on authoritative presence. One of the more amusing discoveries that Mengzy came through her conversations with research subjects were stories of parties being held in local Chinese restaurants.

That period of Hong Kong’s rave evolution set the way for the new era of partying we see today. However, the idea of rave is still an immortal subject to today’s youth, and it’s the parallel of how rave culture still exists that excites Mengzy even more. There’s the resurgence of old school production aesthetics in new music, there’s the growing demand of DJs who dig for music retrospectively and promoters still scout for random locations, such as Yeti Out’s adventurous takeover of the infamous ChungKing Mansions on Nathan Road. The essence is still there, it’s almost genetic.

My conversation with Mengzy slowly winds down as we circle back to why we’re sitting down over this topic. I then explain to her about my brief involvement in Hong Kong’s club history — as a person who grew up to only be able to properly enjoy the latter part of Hong Kong’s primal 90s, my infatuation with dance music didn’t start with international DJs or clubs or festivals. It started with my local scene, and till today, some of those DJs are still my personal heroes. To know that an intelligent soul has taken on the cumbersome task of studying and documenting a very rich reminiscence gives me some assurance that the legacies I grew up with will remain intact and for future generations to take heed from.

Just as I put my pen down, Mengzy humbly adds, “I’ve been so floored by how generous people have been with their time to help me by giving interviews, connecting me with further people in the scene, or in one case, giving me a stack of zines in mint condition that are more than 20 years old without blinking an eye. What’s not surprised me? Hmm… it’s hard to think of something, the research keeps surprising you and the best advice my supervisor’s given is to always, follow the research and let it lead you where it wants to take you — it’s almost like you don’t have control over it sometimes.”

Mengzy and Mixmag Asia would like to thank the following people for their contribution through words, images and their fact-checking skills (despite the memory loss): Jon Nepomuceno, Simon Birch, Andrew Bull & Nick Willsher.