Features

Features

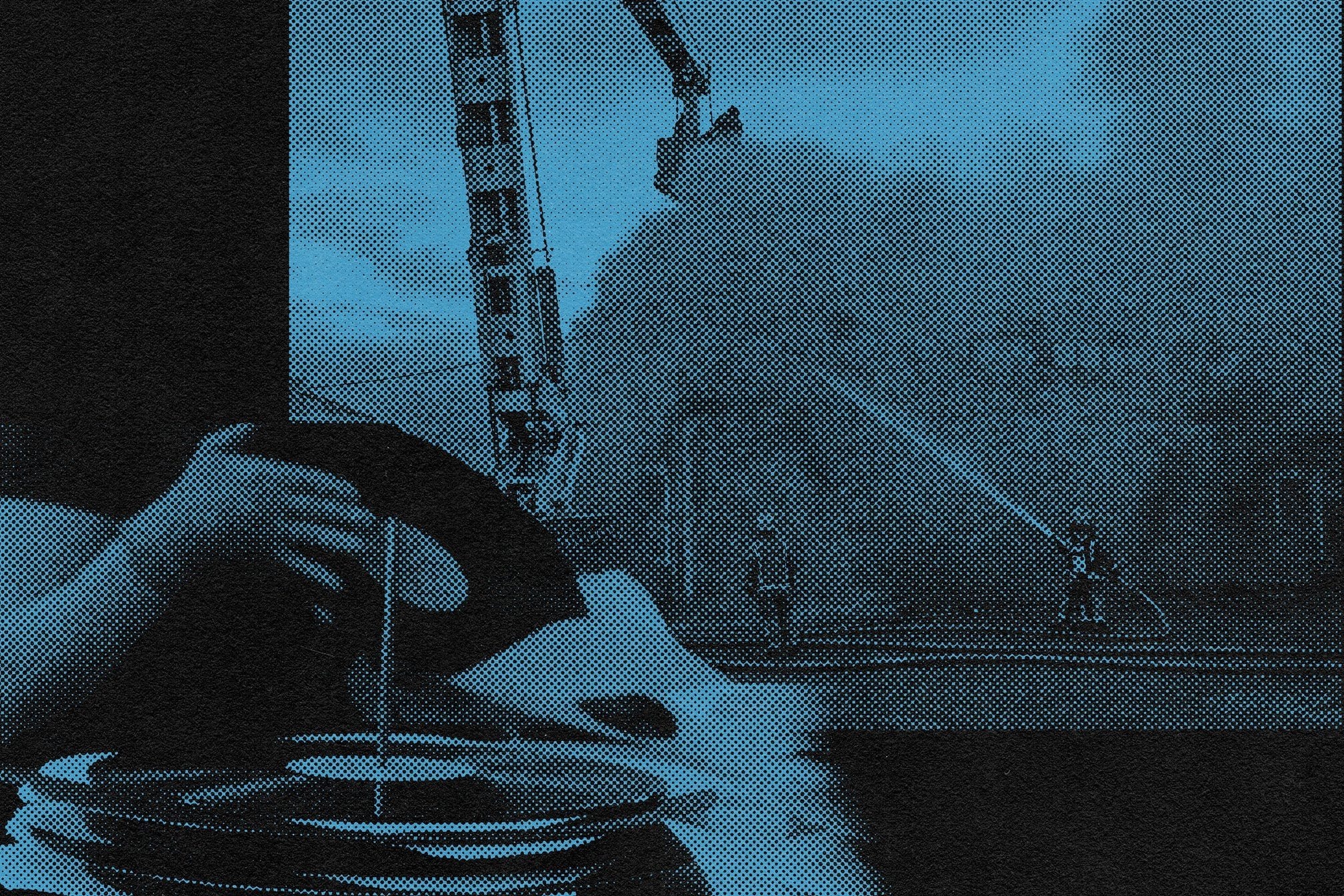

The vinyl straw: Why the vinyl industry is at breaking point

The industry is at its strongest since the advent of the CD disk, so why has it become near-impossible to get music pressed onto wax?

It’s been difficult to avoid the colossal success of vinyl over the past two years. Sure, sales have been steadily rising since its initial resurgence in the early ‘10s, but after another record breaking year in 2020, our consumption of vinyl has more than doubled in the first half of 2021 alone. Despite this, reports of huge increases in wait times to get records pressed, errors in manufacturing and labels abandoning the format altogether are rife. So why is the vinyl industry in such a state of chaos?

Overwhelming demand at pressing plants, rising shipping costs, a worrying lack of materials, and a renewed interest from major labels have pushed a manufacturing process that was already in decline to breaking point. Despite its historic significance within dance music, the current impediment in producing vinyl records has put a spotlight on its role within the scene. Does music really have to be pressed onto wax to be legitimate? Is vinyl the only way you can physically release? Is it time to look at more sustainable avenues?

“I love vinyl, that’s what's so crushing about all of this,” says Tomas Fraser, who runs Independent label Coyote Records. Fraser, like many small label owners, has been forced to stop pressing onto vinyl, having done his last run on wax in 2019. “ I don't know how it's gonna fix itself. I just find it really irritating, to be honest. No one seems to care either.”

So, how long is it taking to get a record pressed currently? In an email to customers, Lobster Theremin’s distribution service is currently giving estimates of 20 weeks, though, from labels and artists that we spoke to, estimates from manufacturers varied from just 10 weeks to an entire year. None of this accounts for delays, mistakes or shipping problems.

Lizzie Ellis, a Bristol-based freelance label manager working across a number of labels, has experienced firsthand the havoc caused by current wait times paired with unforeseen impediments: “We sent off a record in February, and we’re basically now at the back of the queue again — we got the test pressings back and they were messed up.

“In all my years working with labels and manufacturers, I've rarely had to send test pressings back, especially for plants with a reputation for creating good quality records. All I can think is it must be that the plants are super overwhelmed and they are making mistakes, but for us, that means that we’re in limbo with [the release].

“We’ve had similar problems with waiting too, I was sorting a release for another artist and the same plant had said the earliest would be late February next year, for a small record label that basically means it isn’t happening.”

For those wanting to press smaller runs of records, an extended wait time can mean the difference between being able to release physically or not — consumers are less likely to buy a record if it means having to wait in excess of five months to get their product, and to press without pre-orders is risky if the record ends up not selling, particularly with the notoriously tiny margins on vinyl production.

Despite these wait times, vinyl hasn’t seen this much of a boom since before the advent of the CD disk. In 2020, vinyl outsold CDs for the first time ever, and 2021's sales figures have already shot well beyond last year's.

It isn’t showing much sign of slowing down, the Global Record Sales Market report 2021-2026 has predicted that the vinyl industry is expected to be worth $481.5 million by 2026, as opposed to its valuation of $179 million in 2019. In a recent study, 15% in the 16-25 age bracket (or Gen Z) said they have bought a vinyl record in the past 12 months, higher than the 11% of millennials who’ve done the same thing. Amazon even announced their foray into the vinyl market with the Vinyl of the Month Club back in June, which will deliver represses of famous records to buyers' doors every month.

So why the sudden increase in popularity? The pandemic and various worldwide lockdown measures have been a key driving force, cutting off our access to live music and clubs, and driving up digital and physical music sales. For fans wanting to support their favourite artists and labels through financial difficulty, Bandcamp Fridays helped drive up the sale of vinyl, with all proceeds going directly to the seller. Rolling Stone reported that in 2020, the initiative brought in $40 million for sellers during the pandemic. Bandcamp told Mixmag that around half their sales consist of physical merchandise, led predominantly by vinyl, and during Bandcamp Fridays in 2020 physcial sales increased by 107%.

Pressing plant capacity can't keep up with the demand. An anonymous source told Billboard that worldwide there was the capacity to manufacture just 160 million records a year, but to meet current demand that capacity would need to rise to between 300-400 million. It’s thought that there are only 100 pressing plants worldwide currently, with just 10 that have the capacity to produce large amounts of records. The majority of which are either owned by labels themselves, have specific links to industry leaders or cannot take on smaller orders.

For independent labels, the only option is to hunt down lesser-known UK-based or EU-based plants, but with larger plants unable to cope with the massive influx of orders, even smaller outfits are having to take on orders from major labels, pushing others to the back of the queue.

“I've spent most of this year, talking to loads of people researching, trying to find places that have a shorter turnaround, which is basically nowhere other than a few really tiny independent manufacturers,” says Lizzie Ellis. “Then everyone is trying to keep details of plants they've found on the down-low, they don't want to tell everyone or that plant will get overwhelmed as well.”

For many, the increase in interest from major labels is seen as the main cause of pressing plant delays — larger plants are thought to prioritise big orders and anything that overspills is mopped up by the small, independent plants that once prioritised independent labels but are now being apparently swayed by the big orders, and big influence.

“Most of the vinyl you’ll buy from stores like Juno comes from [a few big plants],” Tomas Fraser agrees “the whole industry is vying for a few small slots, so labels like mine are gonna get squeezed out."

For pressing plants, it makes economic sense to make larger runs of records. Producing in bulk is cheaper and simpler in the manufacturing process — the “plates” used to press a record involve creating a sample record using lacquer and unique metalwork that can be used to press over 20,000 records, but this tends to be one of the most expensive and time-consuming parts of the record-making process.

“In the early '90s, most titles, even totally unknown white labels, would press tens of thousands of copies,” I Love Acid honcho Posthuman tells us. “Today, it's usually just a few hundred. So while the overall number of vinyl being made may be similar, there is an insane increase in the number of titles. This is putting a huge demand on metalwork and as a result, there are long waiting times for lacquers to be processed, on average three or four months. That's before you even get a single record pressed.”

However, major labels “clogging up” pressing capacity is certainly not a new thing, in fact, it’s been a major gripe of independent labels since the original resurgence of vinyl in the early 2010s, and was reported on as far back as the advent of record store day in 2007.

Tom Lea, founder of Local Action Records, believes that blaming majors could be a red herring, “Majors clogging up pressing plants has been happening for a while - I don’t think we can fully pin these recent delays on vinyl reissues of ‘Three Lions’ or whatever,” he says.

“It’s been the case since I’ve been running this label - majors are forever pumping out reissues. People don’t seem to remember that vinyl has always been unreliable. It’s tripled recently in how long it takes, sure, but it’s always been inconvenient.”

It seems major labels are also feeling the pinch from the current state of the industry. The forthcoming release of ABBA’s ‘Voyage’ In November is reportedly holding back the pressing of music from Ed Sheeran, Adele and Coldplay, with doubts they will manage to get physical copies in store for Christmas.

A source from Warner Records, who wishes to remain anonymous, told us that there is “infighting even within major labels — Parlophone, for example, will be clogging up manufacturing plants with a Fleetwood Mac or a David Bowie repress, which then means the [rest of the label] have to shelve any vinyl projects from newer or developing artists.”

“It prices out the artists who aren’t that top 1%,” they add. “The best-case scenario for our newer names is that we can get vinyl out several months after the digital release — at which point it’s so difficult to drive up demand for them because the campaign is essentially over, meaning we would not even cover the costs of doing it. It’s why the vinyl market is so saturated with reissues/repacks or limited edition box sets right now, even for us, it’s the only way of selling vinyl that isn’t loaded with risk.”

What buyers are wanting from their vinyl has also changed, with an ICM poll in 2016 revealing that 48% of buyers don’t play their records. The British Phonographic Industry (BPI) revealed in their All About Music 2020 edition, that one in five vinyl owners don’t even own a record player. The same report reflected that many of those purchasing vinyl records have usually listened to the track/EP/album on Spotify beforehand.

“It’s a collector’s item now, it’s not something to consume or play,” comments Tomas Fraser. “Sure, there’s a demand for vinyl but not in a functional sense. The demand is shifting and people are wanting digipaks, full-colour sleeves. Small labels can’t make that, that’s two grand a time. Now we’re just pressing vinyl because it’s validating and it makes you feel like a real label, but people are rarely taking those records home to play them.”

Posthuman agrees: “People want artwork they can hold and sleeve notes they can read while listening. Fans who are buying records are way more interested in its physical form, rather than in the past when it was the only way you could get music. There is such high demand right now for unique looking records — coloured vinyl, splatters and marbling, picture discs, shaped records, etc.

“These require a huge amount more time and labour to create, again heaping up demand on pressing plants time. Some plants have said they will not do any coloured vinyl at all until they have cleared their current backlogs.”

The backlogs have been caused by multiple factors. The queue itself, the increased demand in vinyl — but also that most unprecedented of unexpected occurrences: the COVID-19 pandemic. Just like most of our global manufacturing, the vinyl industry has been hit hard: plants have been forced to lay off staff; social distancing measures in various countries have meant that fewer bodies are on the floor to churn out the suddenly skyrocketing demand for records; and the spread within plants of the virus, as well as track and trace measures, has seen the closure of entire factories overnight.

A report from Pitchfork during the first few months of the pandemic last year reported that many large manufacturing plants in the US had been made to close for up to seven weeks with some being forced to lay off hundreds of staff to make ends meet.

“It's not like everything went back to normal once things started opening up again, staff in the plants were still ill from COVID or having to isolate,” say NAINA and SHERELLE, who started Hooversound Recordings in lockdown and are having to deal with the pandemic’s effect on manufacturing while still growing their label. “There was no way to avoid it unfortunately and everyone’s in the same position. Starting a label in a pandemic is grey hairs central. You just have to learn on the go, adapt and make it work. We’ve been seriously delayed but it simply means we have to plan ahead and be more strategic.”

For plants in the UK, or labels importing records from EU-based manufacturers, Britain's exit from the European Union on December 31 exacerbated the already severe COVID-19 backlog, seeing increased waiting times for shipping, products being held at customs, and the introduction of new VAT tariffs. This means records are taking longer to get to labels, communications between label-owners and plants are delayed, plus there's an inflated shipping costs to sell products to European buyers. While there are pressing plants in the UK, the process of pressing a record means there are always resources or materials that need to be imported via the EU.

“Everything is being held at customs at the moment,” says Tom Lea. “A big reason this has turned into such a nightmare is the cost of shipping and the added delays and issues we’re experiencing just trying to send records to people. Sending a record to the United States is £10 minimum now. That’s a big ask for a customer, and I don’t know how sustainable that is for either small labels or record buyers.”

On December 31, the EU introduced a policy of requiring Important One Stop Shop (IOSS) numbers from digital businesses sending products to the EU. The IOSS is a portal that allows online businesses to pay the correct VAT on products they are shipping into the EU before the product arrives at the border, preventing hold-ups at customs. However these numbers can’t just be held by the labels themselves, every partner involved in the process of selling a product must also have their own IOSS number — and Bandcamp, with whom a majority of UK-based indie labels rely on to connect with customers, didn’t get an IOSS number until August 26 of this year.

“No IOSS number means that the buyer can end up getting charged 20 Euros worth of customs fees,” says Tom Lea, “For UK labels the choice has been to basically charge £30 worth of shipping fees or just don’t ship to the EU. At Local Action we’ve been telling anyone buying from the EU, look if you want this you can either let us ship it now but you might end up with a hefty tax — or wait for Bandcamp to get this sorted.

“My instinct is that delays in pressing vinyl will always be there, you can navigate that. But if shipping costs continue to rise it will be a problem.”

Butterz label boss Elijah agrees, recently tweeting: "Shipping and taxes will be the death of vinyl for small labels, not long production times."

Shortages of materials at every stage of vinyl production has also created an inability for pressing plants to give any real estimate to distributors on how long it will take for their release to be pressed.

Vinyl records are made of polyvinyl chloride (or PVC), a material that is mostly produced in the US state of Texas and due to unseasonal cold snaps in both 2020 and 2021, there has been a worldwide PVC shortage.

Even more disastrous was the February 2020 Apollo Masters fire, a factory that produced 70-85% of the world’s lacquer supply, used to make the acetate plates to press vinyl. The factory was completely destroyed in the fire and meant all production of lacquer disks was left to the only other lacquer producing plant in the world, a tiny Japanese producer called MDC.

Though pressing plants and vinyl producers have found ways to use alternative metals to produce records, such as copper, the results can be imperfect, and considering the high costs of producing plates in the first place, are high-risk if the pressings are faulty and lead to even more severe delays.

Difficulty in importing materials to produce vinyl and exporting finished records due to Brexit, shortages of staff/extended closures of plants and lack of raw materials has created a perfect storm — that doesn’t appear to have any real end in sight anytime soon.

Many in the industry believe the solution lies with upping pressing capacity, opening new plants and training a new generation of manufacturers in vinyl production. Despite the steady rise in popularity for vinyl, pressing capacity has gone down, with experts estimating that there needs to be capacity for 200 million more records to fulfil current demand.

“We need a younger generation of engineers, there’s an acute lack of available staff,” says Posthuman, “Most plants are still running on presses that are either refurbished or adapted from old 20th-century machinery. We also need pressing plants that stick by and prioritise their long term customers rather than capitulating to the majors. It’s a kick in the teeth for independent labels who have kept the plants in business over the last 20 years, who now find themselves at the back of the queue.”

Tomas Fraser agrees: “I’m hopeful we can get a new wave of pressing plants and micro plants to help. I think vinyl will always be there. It’s going to be the case where the records you do buy, they’ll be the ones that really mean something to you.”

Some good news comes from business partners Daniel Lowe and David Todd from Middlesbrough, who noticed the severe lack of pressing capacity while trying to put together a charity compilation in early 2020 and decided to do something about it. They opened their new Teeside-based pressing plant Press On Vinyl just a few weeks ago.

“We saw things get from bad to worse around this time last year,” David Todd tells us, talking in his car outside the plant, away from the hustle and bustle of final preparations. “For us, we were just like a lot of these label owners, completely frustrated by wait times, so we decided to get serious and build a plant right in our hometown.”

“We're not ignorant to the history of Middlesbrough, we've got a long history of manufacturing great things, steel, shipbuilding. But there's a wealth of knowledge from other manufacturers and buildings from other sectors that have helped us build a good team.”

Press On Vinyl, Todd assures us, will not be allowing anyone to skip the queue, promising that all labels - big or small, large run or small run - will get the exact same treatment. “We want everyone to have the same access, no matter if you’re having runs of 300 or 3000, everyone gets a good lead time. We’ll be doing short-runs starting at 100.

“We’re passionate about that — grassroots and emerging artists and labels are just as important to the industry as everyone else. Relieving capacity issues is a major thing and a major change and we can enact that straight away.

“The UK is crying out for more plants, it's not only a problem for costs and keeping small labels afloat when we don’t have any but for the environment. Shipping large quantities of bulky records takes its toll.”

The real, and urgent concern for vinyl’s detrimental effects on the environment is a key reason for many artists and labels switching away from the format. Nearly every stage of the vinyl production process has negative ecological consequences from its use of plastic, to emissions from plants, to the shipping of both raw materials and records themselves. A report from The Guardian in 2020 revealed that many US pressing plants have turned to shipping over PVC from plastic and petrochemical producers in Thailand with “historic environmental abuses.” Vinyl chloride, the main ingredient of PVC, is notoriously carcinogenic and is responsible for producing toxic wastewater and harmful air pollutants.

The lack of producers for specific materials also means that they need to be shipped all over the world, to scattered plants who then need to ship large batches of records further afield. It’s estimated the vinyl industry uses upwards of 60 million kilos of plastic every year — which equates to 140 million kilos of greenhouse gasses.

Environmentally sustainable vinyl is being explored, record label Needs-Not For Profit founder Bobby Connolly has teamed up with Dutch pressing plant Green Vinyl Records to create the world’s first “100% recyclable vinyl,” with a planned compilation featuring Saoirse, Reptant, Sansibar, Luxe, Pugilist and Hassan Abou Alam.

Their production process uses injection methodology, which injects plastic straight onto grooves of a record rather than heating PVC up and moulding it — meaning it uses 65% less energy and there’s less chance for harmful pollutants to escape during manufacturing. On top of using recycled PVC, Needs-Not For Profit hopes this could be a sustainable way of producing physical records.

“It's essential that vinyl becomes more environmentally friendly, everything needs to become environmentally friendly,” says Bobby Connolly, “We only have to look at what’s going with the climate crisis to understand that.

“I think injection moulding technology like the one we are using on our latest record will become more commonplace and hopefully soon we will see the introduction of vinyl which is made from recycled plastic. This is the target for us and we will be pushing this innovation as soon as it is available.”

Egyptian producer Hassan Abou Alam who is releasing on the imprint says that, despite loving the tangibility of physical media, he had become apprehensive about releasing on vinyl due to its unsustainability.

“I’m way more confident when it comes to this new technology that’s being pioneered by Needs and Green Vinyl. I’m really hoping this is a big step forward for our industry.”

Another way artists and labels are trying to overcome the issue with vinyl is by looking at alternative ways to physically release their music. For aya, her upcoming Hyperdub release will have an accompanying book that fans can purchase, Murlo’s ‘Unearth’ EP will be released on cassette and in the form of a “fungi identification kit”. Jasmine Kent-Smith even looked into the weird and wonderful world of alternative physical releases for Mixmag in 2019, with producers releasing on everything from USBs, QR codes, T-shirts and zines.

“There’s still an appetite to support artists by buying merchandise and other physical products,” says Tom Lea, “I just don’t know if vinyl is the practical way to do that. What’s happening now - which wasn’t before, and I think is a really healthy development - is that artists aren’t necessarily even wanting to release on vinyl. With E.M.M.A.’s ‘Indigo Dream’ she specifically wanted to explore other options that suited the album better, and with DJ Jayhood it just wasn’t a format he had any investment in.

“Unless you do 300 copies of vinyl you're not going to make much money. But if you're a label that's just starting out and you're dropping a grand on tonnes of records and if you only sell 50, you're screwed and you're sitting on hundreds of records. Whereas with things like tapes and prints you can just put pre-order up and if you only sell 50 then you make 50. “

Majors are among those looking for alternative methods, an anonymous source for Warner Records told us: “We’re really in talks right now about how we can reshape our physical offerings.”

“For our up-and-coming artists we’re really exploring things like merch/CD bundles instead, collaborating with brands to make things like clothing, accessories, and it ends up being a massive sales driver, it can get the artist in the charts! I think this issue with vinyl is driving labels to get creative and come up with ideas to get around it.”

Dubplates are even having a resurgence. Though expensive, acetate disks can be made to order without the risk of not being able to sell sizable quantities.

“For me cutting 20-30 dubplates has been so much easier than bothering with vinyl,” says Tomas Fraser. “Fans who want the physical release can buy then but we’re not sat on 200 records and losing money. They are a bit rough and ready, but people really like that.”

Lewis Joyce from South London dubplate specialists 1-800-DUBPLATE originally had to crowdfund his record store and cutting shop in 2019, but since its opening has seen such a massive increase in demand that he’s now looking to double the production capacity of his shop and buy another acetate cutting machine.

“I’m fully booked until October/November,” he says, speaking on the first day of September. “I’m doing runs for labels and stuff and single-orders are coming in every single day.

“There’s been a huge knock-on effect on us from what’s happening in pressing plants right now. More people are coming and even we’re starting to get backed up and then I can’t turn around things as quickly as people want. I had a guy two weeks ago come in and he asked me to do 250 10” records by the end of September, and I was like ‘no’ [laughs]. It was because he couldn’t get it done at a pressing plant.”

So where does this all end? What will be the final outcome of the flux and havoc that is the industry in its current state? Is vinyl, currently in all its metamorphic boom, destined for an earth-shattering bust?

“The majors and Record Store Day will burn out soon,” Posthuman believes. “They are already scraping the barrel. As soon as it isn’t profitable they will jump ship just like they did before. There has to be a saturation of Led Zeppelin and Elton John B-sides where the public will just say ‘enough is enough, we’re not buying any more’. I don’t think this crisis will last for much longer.”

Can the industry go back to how it was? With label-owners and artists considering now, more than ever, if vinyl is a sustainable way to release music — will it be as simple as vinyl returning to its more underground origins that it was existing comfortably within before the vinyl upsurge?

“Honestly, if vinyl didn’t exist tomorrow it wouldn’t affect me one bit,” Tom Lea laughs, “I think other people feel the same, that actually it would be a huge relief. Everyone knows it’s more trouble than it’s worth, it’s these values that are attached to it.”

aya tweeted her thoughts when asked if she would release her new album on vinyl: “The release format value hierarchy the music industry works on is fucking clapped given some of the best music is coming out only on Bandcamp, meanwhile pressing plants are being held up by Madness reissues that will sit unplayed on the shelf of a 55-year-old graphic designer called Stuart.

“I’m in no way sending for anyone that manufactures and distributes vinyl. I just want to take the opportunity to call some of these issues into question and try something different."

It’s clear the vinyl industry in its current state has become completely unsustainable. Despite massive interest from buyers, it’s been impossible for those on every level of the music industry to put out functional releases on wax. But without a “next generation” of vinyl manufacturers in sight, a scarcity of materials and a slew of labels being forced to abandon wax as a form of physical release — the question is: will the industry even exist for much longer? And are attempts to maintain it simply prolonging its inevitable decline?