Interviews

Interviews

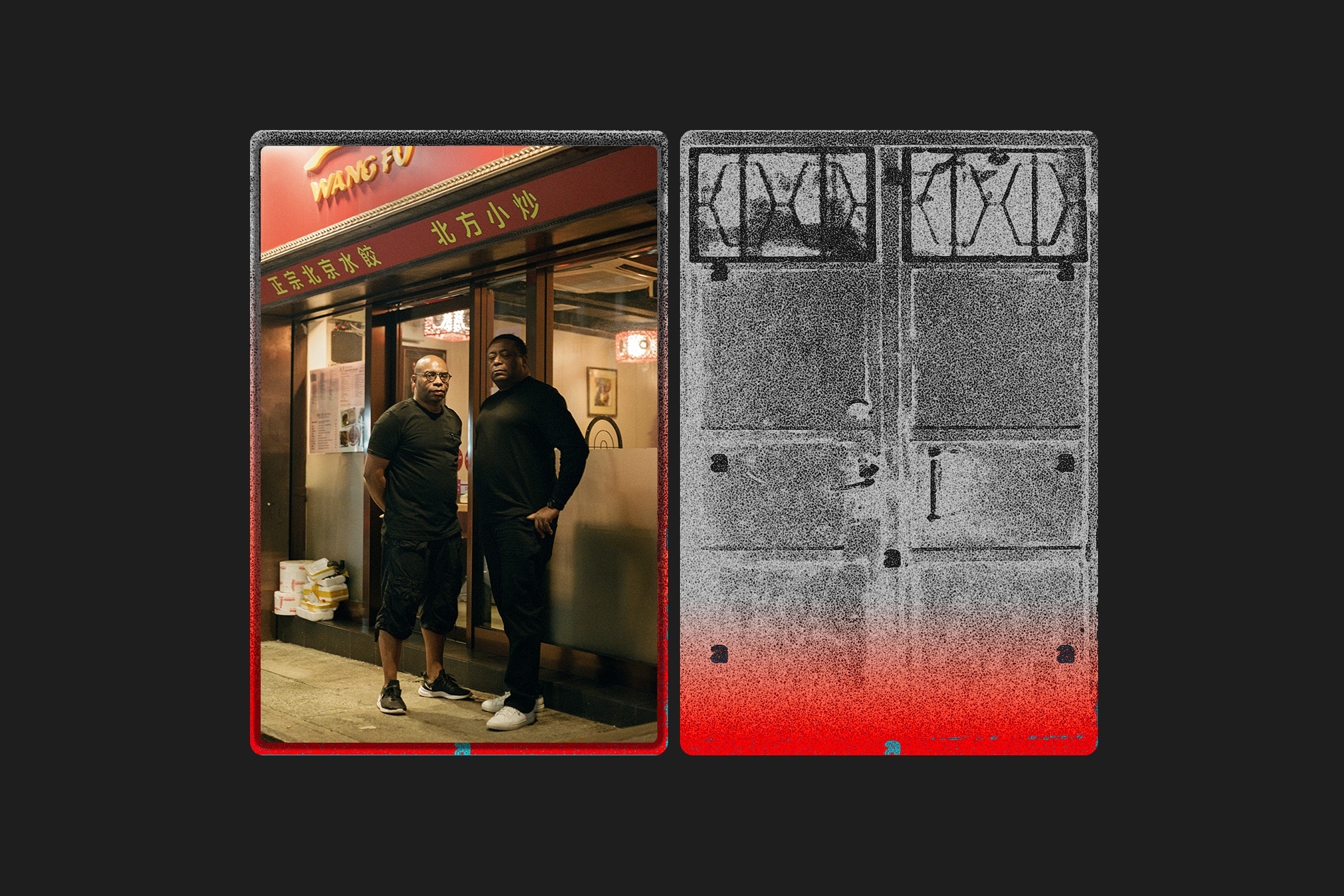

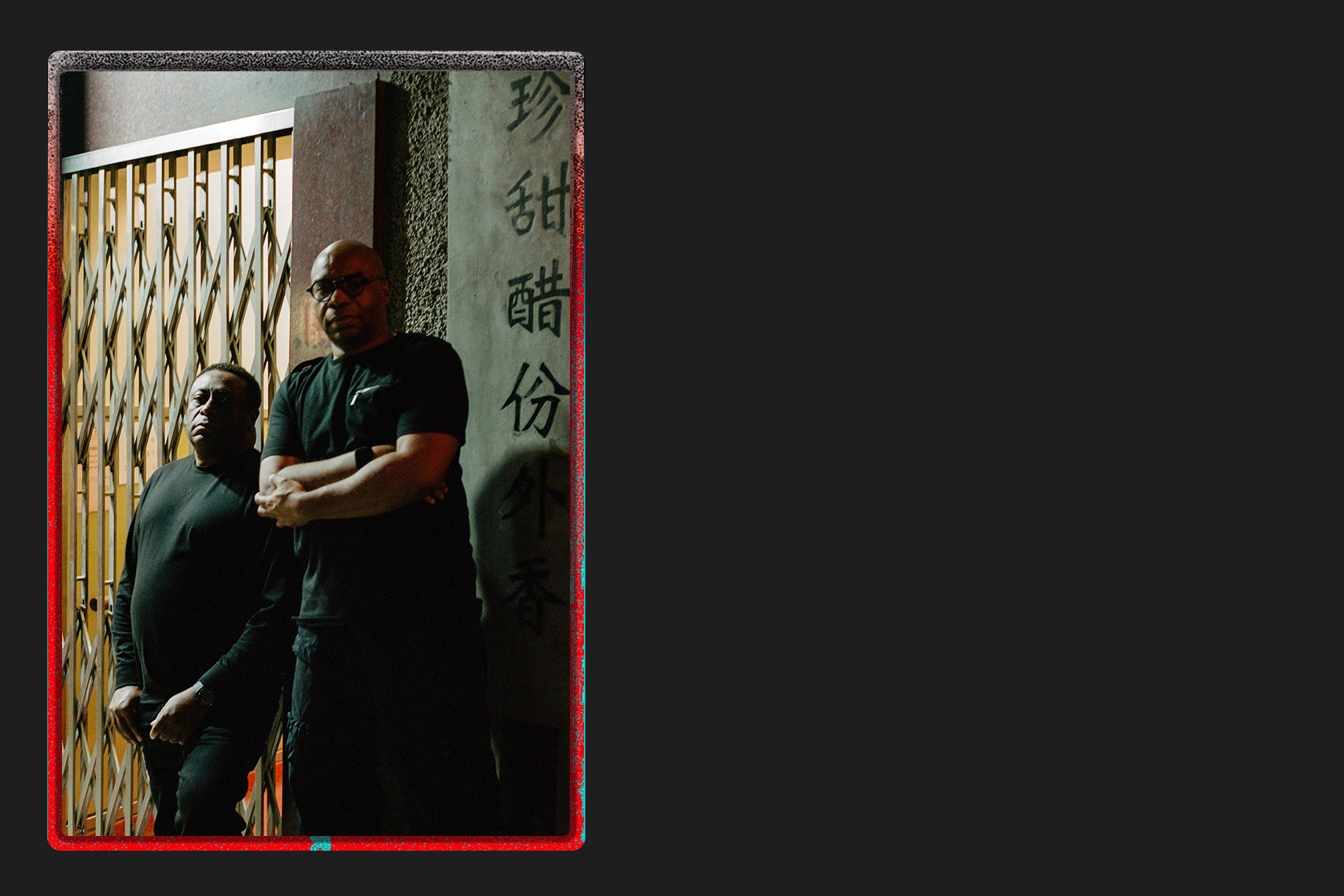

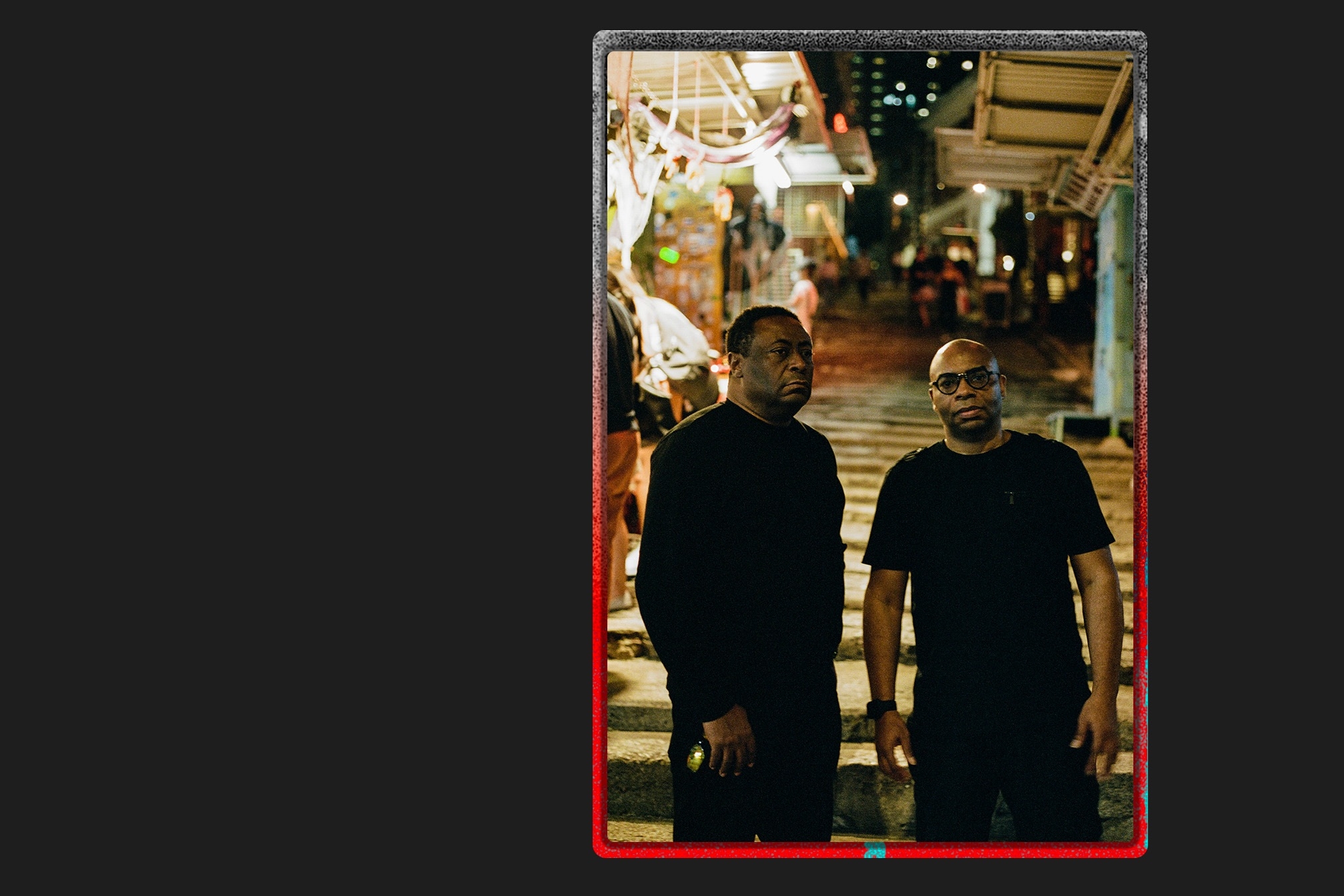

Brothers gonna work it out: the accidental genius of Octave One

Adam Wright chats with the Detroit techno duo about hardware, hard techno, and their connections to Berlin over beer and dumplings in Hong Kong

“Happy accidents” is a phrase that comes up a lot in conversation with Octave One. Of course it does: since they emerged as a part of the second wave of Detroit techno in the late 1980s, Lenny and Lawrence Burden have built up a reputation as a towering live act and released a revered back catalogue that all came about pretty much by accident. And in a scene where it’s easy for artists to take themselves a bit too seriously, the brothers stand out as genuinely happy guys.

Octave One arrived in 1989 with 'I Believe', their debut track released on Derrick May’s Transmat label and one that secured their place among other artists from the second wave including Carl Craig, Robert Hood and Jeff Mills. In the more than three decades since, Octave One have remained relevant simply by doing their own thing. They’ve ignored musical trends and defied categorisation as a purely techno act, often straying into house music territory via their aliases such as Random Noise Generation.

Lenny and Lawrence are the public face of Octave One, and the ones who take the music on the road for live shows powered by an impressive array of hardware. But the Octave One family brings together a large part of the broader Burden family itself, with musical input from the other Burden brothers Lorne, Lynell and Lance. But mainly it’s been Lenny and Lawrence who have spread the Octave One gospel over the world during the past few decades, and Hong Kong finally got to experience an Octave One live show when the brothers appeared at the Shi Fu Miz festival on Cheung Chau at the end of October.

Before their set at Shi Fu Miz, Mixmag Asia sat down for dumplings and Tsingtao beer with Lenny and Lawrence. And we enjoyed a wide-ranging conversation that took in everything from their roots as both music lovers and musicians, the current state of techno, the nitty-gritty of their all-hardware setup and why they aren’t big fans of doing remixes.

Welcome to Hong Kong! This is your first time here, right?

Lenny: Yeah, this is our first time here as Octave One. It’s my first time here ever. Lawrence has been here before, but I don't think he played here.

Lawrence: I was here back in the 1990s with Derrick May, Jeff Mills and Mike Banks. Jeff and Derek were doing a gig, and we all ended up here hanging out together.

What are some of the other places around Asia you’ve played before? Have you had any memorable experiences here over the years?

Lenny: We've been to places like Singapore, Beijing, Malaysia, Tokyo, Osaka, India...

Lawrence: And what’s memorable in places like Japan is that the crowds are always so polite. We’ve done a few in-store shows there and everyone wants to meet us, everyone queues up in one line… But the shows are crazy, just insane, all this yelling and guys with their shirts half off.

Lenny: But it's not all the same. We play so much in Tokyo and we’ve definitely got a much better feel for that. But in places like Singapore, where we have played two or three times, it’s always good but it's not the same energy. There's different types of energy. In certain places when you have a very structured life and when it's time to go to the club, you kind of let loose more.

Have you connected with any regional techno artists in Asia before?

Lenny: Back in the day, Ken Ishii contacted us about a mix he was doing for Sony. I think that’s the first time he was doing something big. But Ken's also been to Detroit and there’s a video of us playing with Ken sitting behind us. This was years ago. I think he's the first Asian artist that the guys in Detroit connected with. He's just a great guy.

Do you come from a musical family? Who were some of your musical influences in the family?

Lawrence: Our mother first pushed us into music and she made us all take piano lessons when we were like six and nine.

Lenny: After that, at school, I played drums, played a couple of horns, but I didn't play well. It wasn't until I discovered electronic music that I was able to find my footing. But the lessons allowed us to develop that love for music and build that base. My talent wasn't in playing those organic instruments; the electronic stuff is what allowed me to express myself. But Lawrence is an incredible sax player. I never had that kind of luck.

What was some of the music that really inspired you when you were kids?

Lawrence: At home, we were exposed to everything from Earth, Wind and Fire, Stevie Wonder, and Elton John. Our dad was into The Beatles pretty heavily, and then there were the local [Detroit] rock guys, like Iggy and The Stooges.

What was your introduction to electronic music and what are some of the earliest electronic music you remember hearing?

Lawrence: It would have to be Kraftwerk first. Because of the local DJ the Electrifying Mojo, we had really good radio. That’s where we first heard Cybertron… Yellow Magic Orchestra, too. Mojo would play this stuff on the radio every night.

Lenny: The reason that so many of us in Detroit make electronic music is because of the Electrifying Mojo. This was when we were real young, and we’d hear Yellow Magic on the radio, we’d hear Kraftwerk. And he’d play the full side of a record. He’d put the needle on and let the whole side play. So it wasn't just a song. It was like you owned that record.

Lawrence: He’d also play the B52s, Ted Nugent …

Lenny: And this is why everyone from our era is kind of open to combining electronic music with funk and soul. That’s how it was presented to us, that it was all the same. It wasn't like, “This is electronic, or this is this, and this is that”. It was all just music.

Read this next: Why electronic music lessons should be taught in secondary schools

How did you all get started making music of your own?

Lenny: We started DJing in ‘85, ‘86. We were actually very eclectic, and playing a lot of different styles, like pop music and electronic and house. And that was our gateway to buying a drum machine because we wanted to use one when we were DJing or even to start making our own music. We ended up buying a [Roland] 909 and once we heard that machine, we're like, “Oh, this is what we’ve been hearing in house and then in techno”. It was instantly recognisable. Then I bought a Yamaha DX100 synth, which makes really good basslines. And then from there, we started trying to emulate records, but we were never really good at emulating anything. We developed our own style, but it all came about accidentally.

Your first single 'I Believe' came out in 1990 on Derrick May's Transmat label. How did you meet Derrick and the other early techno producers?

Lawrence: We had been working on some tracks in Juan Atkins’ studio. We usually rented Juan’s studio when he went to Europe from his brother Aaron, but Juan had no idea. We’d go in there and start working on tracks, and Kevin Saunderson lent us his keyboard - he had a brand new [Roland] U-20 that had just come in. We started playing with the keyboard and that's how we came up with 'I Believe'.

Lenny: Then a friend introduced us to Anthony Shakir, who ended up engineering our session. As he was engineering, he was also making music with us. He was the only person who ever taught us anything about making music. Everything else we learned on our own. We never had a mentor. We were never a part of any of the cliques. When we finished, Anthony sent it to England where Derrick and Neil Rushton were putting together the second compilation ('Techno 2', the follow-up to the seminal 1988 compilation 'Techno! The New Dance Sound of Detroit'. Neil wanted it for the album, but Derrick was saying, “Hey man, this is a Transmat record!”. We had been sending demos before that to Transmat, but Derrick had this thing like a wicker basket where he would throw all the demos without listening to any of them. But 'I Believe' was released as a single on Transmat 12 months after the compilation.

After your debut on Transmat, you started 430 West Records. Apart from some releases on Tresor, this has been the main outlet for your music since 1991. Why have you stayed independent all these years?

Lenny: Derrick never released a lot of records, he was very slow, and at that time he really wanted us to do another I Believe. We're like, “We're not going to do another 'I Believe'”. We decided that if we wanted to put our music out, we wanted to do it on our own terms. We weren't going to wait for anybody. So we kind of figured it out. This is pre-internet and there was no one to give you the information. Even figuring out how to record a master, you got a little piece of information here, a little piece of information there. And we finally figured out how to put a record out.

Our first record [on 430 West] was 'Octivation' and it started blowing up. We were shipping thousands of them. But the second record? We couldn't give it away. So we got grounded on our second record and were like, “Okay, maybe we're not going to do this as fast”.

Your brother Lynell also helps run the label, right?

Lenny: Lynell has always been a partner in the label. Later on, our two younger brothers, Lance and Lorne, were introduced to the production side of things, so now when we play, we play music from all five of us. Right now they're probably making music. Maybe they'll send us something and we'll start working on it when we get home. It's kind of how the Beach Boys were: Brian Wilson was at home making music and the other boys went out on tour.

This is the reason we're able to do so many different styles. We're not necessarily “techno techno” and we're not necessarily “house house”, because we’re five different people with five different opinions. We’ve always been in the middle and that allows us to play with a large variety of DJs or producers. It could be Honey Dijon one night and Adam Beyer the next. We're all over the map.

Read this next: The 5 pieces of kit every hardware musician needs, according to an expert

Apart from your own label, you’ve also had a few releases on the Berlin-based label Tresor. Have you maintained a fairly close relationship with Berlin over the years?

Lenny: Our manager is based in Berlin and for the longest time our booking agent was based in Berlin. For the longest time, we were doing Berghain once a year. The vibe in Berlin is very important to Detroit techno. Most of us have a connection to Berlin somehow, whether it’s someone in our extended family, our musical family, our team. Somebody’s always in Berlin. I think that’s the first city in Europe we went to, either Berlin or London. It was the first place we wanted to see.

In around 2005, we wanted to do something that was going to bring us back to our techno roots, and that's how we ended up doing the Off The Grid album and DVD with Tresor. We had been touring a lot and decided that we wanted to do a live DVD because we had just finished a DVD project with Jeff Mills, The Exhibitionist, and decided to do one of our own too.

Detroit techno has sometimes been quite political - Underground Resistance are probably a good example - but Octave One seem to have always kept the focus purely on the music. Was this a conscious decision?

Lawrence: We wanted to escape that. That's why we made music. We wanted to escape the things that were with us every day. We wanted the freedom to just be artists. We had crummy jobs that we worked nine to five and we wanted to forget all of that. We wanted to create and things just flowed out of us this way.

Lenny: We never dreamed of doing this either and that's where the artistry comes from. A lot of our contemporaries dreamed of being DJs or whatever. We just wanted to make a record. Once we did that, that was a huge accomplishment.

Then we we wanted to make another record and another record, but we never sat down and said, “This is our what we believe in”, or whatever. We just made music. And then people started calling us legends, but we’d never thought about it that way. In my mind, I just started doing this yesterday, but other people tell me I've been doing it for 30 years.

Read this next: Movement Festival is a celebration of techno's past, present and future

Octave One’s techno has usually been quite uplifting and positive, but in recent years a lot of techno has been quite dark and there’s been a return to very hard techno this year - what’s your take on the current state of the scene?

Lenny: We've seen a lot of trends and this is just another trend. I think right now it's important for them to have that darkness. Coming out of the pandemic, everybody just wanted to bang hard. And you kind of understand it. It’s just like any other music at any other time, like when punk was big - it's something that's necessary for that time.

We've seen so many electronic music trends, too. Right now, these kids need to express themselves with that hard, fast music. But EDM was a gateway for people to find something different. Maybe this will be the same.

Your live show utilises a hardware-only setup — what are the challenges of touring the world as a live act with lots of hardware?

Lenny: We have evolved a lot over the years. Initially, we were bringing a lot of our classic gear on the road, but that was a horrible idea as we tore a lot of things up. Now we have multiple copies of everything we travel with. We always travel with an MPC [sampler and sequencer] so we have three of those, multiple versions.

We have a few Dave Smith Tetras. This stuff just gets broken, you know? So we just switch stuff out and when we get a chance to get it fixed, we get it fixed. Sometimes we don't. We have resigned ourselves to buying a lot of gear. And this is not our studio gear either. This is only our live gear.

Then there’s the weight issue: our cases have to be 23kg, depending on the airline, so there’s a bit of a science to that. We're always looking for gear that's going to add more functionality to the show — more freedom in the way we play.

Has any piece of hardware been with you from the beginning?

Lenny: Our 909. Once we foolishly let one artist borrow it, but that would never happen now. Then they started handing us records which had our sound on them. We realised that the machine itself was part of our sound. One individual 909. Because those circuits degrade over time and that degradation becomes a part of its personality. I can say it a thousand times, but this was completely accidental. Creating our own sound because our gift is not to be able to emulate someone else. And as we're trying to do it, we're coming up with something unique. Accidentally.

On our first five, six, seven records, we didn’t even know what a compressor was. People asked us how we got that raw sound and we tell them that complete ignorance is how you get that raw sound. Completely accidental. Happy accidents. Yeah. I mean, that's basically our whole career.

How did your approach — with Lenny on machines and Lawrence on the mixer — come about

Lenny: I never wanted to be a DJ. Lawrence was DJing all over the place. But there was one gig where the act pulled out and we had to figure something out. So I just kind of put [the hardware] together and I go overboard on a lot of things… So I'm hitting the stage and Lawrence was DJing right before I was going on, and I just couldn't do everything. Lawrence jumped behind the mixer, I moved over to where I had all the gear and that's been our setup ever since. He picked his spot and I picked my spot and that was it. Another happy accident, really.

Lawrence: I went over to the desk and I was like, “Oh, individual tracks? I can do this”. And literally that's our show — I'm playing with these tracks just the same way I was playing with the two tracks on the decks.

Read this next: Orbital: "It’s embarrassing to be called 'icons' but at least it's better than being called 'wankers'"

I’m guessing that no two sets are alike?

Lenny: You have no choice. Things sometimes go wrong. But our job is to make it seem like that's how it was supposed to be. Sometimes we're more successful than others, but we don't want to just stand there. We want to interact with these songs.

How do you communicate with each other?

Lawrence: We don’t talk. There's no need. The music is doing all the talking. We feel it as a kind of pulse, a pace, a vibe. It's a rhythm. We just go with it, we follow it and let it go. We try to give each other space too. And that's hard when you're so creative as individuals. If he starts going in a certain direction, I pull it back and I see where his vibe is going and I'll add to it.

You’ve done some remixes for other techno icons like Dave Clarke and Luke Slater, as well as artists outside the techno world like Massive Attack and Orbital. What does Octave One bring to the table when asked to do a remix?

Lenny: We're not all that fond of remixing. For a lot of different reasons. But if we like your record, we don't want to touch it. Usually, they have to convince us to do it. Like with Orbital and the 'Chime' remix. When Massive Attack sent us a track, we liked the record and didn't want to touch it. They’re like, “Just do something.” We hate it when people remix our records. We usually don't recognise any parts of it. It might be a brilliant track, but it has nothing to do with us.

Detroit has been through some tough times in recent years, but we’re hearing that the city has seen a revival lately. What’s life like in Detroit these days?

Lenny: Lawrence and I live in Atlanta now. But we go to Detroit a few times a year as we still have family there. But the renaissance of Detroit is definitely happening. You can't keep Detroit down.

[Images via Petra Greening and Adrianna Cheung]

Adam Wright from Omni Agency is a contributor to Mixmag Asia; follow Omni on Instagram here.