Features

Features

Inside The Movement of Artists and Fans Boycotting Spotify

The meagre financial returns of streaming for artists has been a point of controversy since its inception. Now substantial investments in AI weaponry are causing musicians, labels, and consumers to further question their relationship with streaming giant Spotify

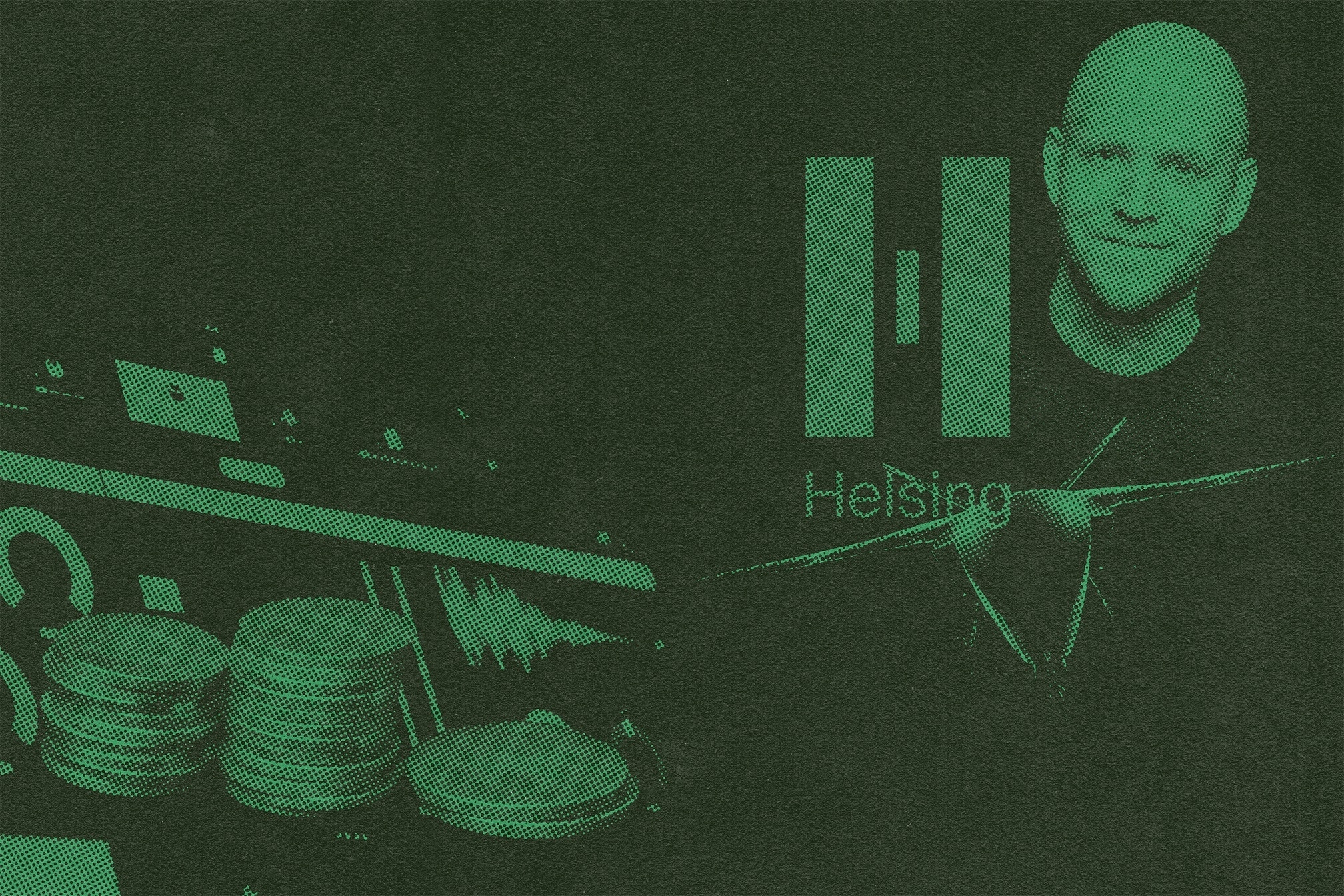

When Michail Stangl learned about Spotify CEO Daniel Ek's initial €100m investment in Helsing — a German company specialising in AI military software — he cancelled his subscription to the streaming giant immediately. The Berlin DJ and curator (also known as Opium Hum) didn't bother saving any playlists or data; he just knew he couldn't be complicit. "Here we have a billionaire who has amassed tremendous personal wealth from the social and financial decline of the masses, then he takes that money and puts it into a weapons company to enrich himself even further," Stangl explains. "I found that so morally repulsive that I quit on the spot."

This was back in 2021; since then, Ek has ploughed a further €600m into the controversial weapons company, justifying his decision by declaring "I am 100 per cent convinced that this is the right thing for Europe." While the initial cash injection didn't receive widespread coverage, this follow-up investment has caused many musicians, labels, and listeners to properly interrogate their relationship with Spotify.

Read this next: Spotify CEO Daniel Ek becomes chairman of AI military start-up following €600 million investment

The platform has been plagued with ethical issues for years. It pays measly royalties to artists (roughly $0.003-0.005 per stream), has promoted the troubling rise of AI-generated music in recent years (although did announce an overdue crackdown recently), and these days prioritises so-called 'lean-back consumers' who supposedly use the app primarily for background music. It seems that for Ek, music is just a vessel through which to extract wealth from others. His entanglement with Helsing has caused a number of people to say, 'Enough is enough.'

"I'm really concerned about the use of AI-driven warfare, so learning about that was definitely a turning point for me," says Martha McCurdy, a former Spotify user who cancelled her subscription this summer. "I believe in people power; making everyday choices on what platforms you engage with is important, whether it's divesting from companies like Spotify or using the No Thanks app to scan for products listed by BDS [the Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions movement, a Palestinian-led campaign using non-violent resistant to pressure Israel to comply with international law]."

Joey DeFrancesco, founder and organiser at artist advocacy group UMAW (United Musicians and Allied Workers), insists that a global mass movement is required if campaigners are to put real pressure on the corporations that control music streaming. "We need to collectively build power, so that we can have thousands of artists leaving Spotify at the same time," he says. "Think about it like a factory: if one worker quits the factory over some bad working conditions, it sends some message to management, but if all of the workers in the factory are prepared to leave and organise at the same time, that's how you really make change. We need to get people organised enough so we can have real power against these streaming giants, and also use public policy to put pressure on them."

UMAW and other groups have been pursuing this two-pronged approach for some time. Alongside advocating for practical steps like higher artist royalties (a minimum of one cent per stream), a more user-centric payment model, and the publishing of contracts between streaming services and major labels, campaigners have also focused on getting boots on the ground.

Protests have taken place outside Spotify offices in the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, Brazil, Spain, and several other nations as part of the Justice at Spotify Day of Action, while targeted campaigns such as Boycott Barclays and the SXSW Festival boycott have had a significant impact.

Read this next: Inside The Gathering 2025: exploring access, collaboration & sustainable music futures

Boycott Barclays, launched by the Palestinian Solidarity Campaign, saw over 120 artists pull out of Brighton's The Great Escape lineup, ultimately causing the UK bank to suspend its sponsorship of Live Nation, which previously operated several UK festivals including TGE. The latter movement resulted in the Texas festival cutting ties with the US Army and defence contractor RTX Corporation, which according to the PSC "has supplied Israel with a range of weapons and military technology used in its militarised attacks on Palestinians."

These are hard-fought victories that give hope to those divesting from Spotify and trying to separate the music industry from warmongers. But it's worth noting that consumer shifts away from the world's foremost streaming service aren't just about genocide. Bluesky user @z-axis.gay, who recently switched to YouTube Music "for a few different reasons," tells me "the platform is just not good anymore. The prevalence of AI artists is awful: my partner will be listening to this supposedly curated Fallout (the game) playlist, and then a band with AI-generated cover music will start getting mixed into it? The yearly recap used to be cool but when they tied in AI with that, it became not fun."

Also on Bluesky, Ian Harvey tells me, "I avoided [Spotify] because they don't pay artists properly. This [Helsing investment] is a whole extra level of shitness," while another user, April, adds, "after migrating to Deezer I'm enjoying my music experience much more.”

Meanwhile, a growing number of artists — mobilised by a mixture of concerns including royalties, AI, and the funding of warfare — are refusing to channel funds into Ek's company. Dutch label Kalahari Oyster Cult recently pulled their entire catalogue from Spotify, with artists like Spray, Maara, and Flora FM removed from the platform and the label stating "we don't want our music contributing to or benefiting a platform led by someone backing tools of war, surveillance, and violence." DJs like Skee Mask and Darren Sangita pulled their catalogues a while back, and over the summer, a range of artists, including King Gizzard & The Lizard Wizard, WU LYF, Deerhoof, and Laura Burhenn followed suit.

Like Stangl, Dario Zenker, the co-founder of Munich label Ilian Tape, was ahead of the curve in boycotting Spotify. "It was surprising to me that nobody seemed to care when the CEO of Spotify first invested in Helsing," Zenker tells Mixmag. "But in the last few years, more people are moving to Tidal and Apple Music. A shift has happened because of what's going on in the world." According to Zenker, when Ilian Tape removed their catalogue from Spotify, roughly 80% of artists backed the decision, and "understood the decision was based on a moral standpoint". The question is, how much more ethical are the alternative platforms users are switching to?

According to Stangl, when it comes to financials for artists, "the alternatives are equally fucked. The majority of my Tidal fees go to the artists I listen to most, so it's not Drake that gets my money, but some obscure Japanese metal band, which is an improvement in theory." Reports suggest that Tidal, Apple Music, and Deezer all pay artists a higher average per-stream royalty rate than Spotify. But Stangl adds that switching streaming services "does not address the fundamental systemic issues we're facing. The media ecosystem, recorded music, tourism… they are equally broken and catering to the interests of shareholders, big corporations, and a few management and booking agencies that have a foot in the door with these companies. The challenge is to build alternative economies and ecologies that allow some sort of gradual change."

For many artists and fans, the most obvious alternative to streaming is paying for MP3 downloads or buying music from artists directly via platforms like Bandcamp or Subvert, a newly launched, collectively owned 'Bandcamp successor' kickstarted after the prior platform's Songtradr takeover (and subsequent mass staff layoff). While other streaming services like Deezer have been positioned as a more ethical, artist-friendly alternative to the giants, many people continue to argue that the streaming model as a whole is fundamentally flawed.

"Streaming devalues music; it was never an option for me to consume music like that. I buy vinyl, or if not, I download,” explains Zenker. “I think it's really important to give back to the music community. But it's a tricky issue because some people can't afford to buy music, and you don't want to exclude people in parts of the world where salaries are much lower and streaming is the only way they can consume music."

Read this next: Six books on how streaming has forever changed our relationship with music

Ultimately, when it comes to the broader public, there isn't as much appetite for supporting artists and shifting away from streaming giants as there is amongst more avid music lovers. But that doesn't mean change isn't possible. The success of campaigns like the SXSW boycott and Boycott Barclays, coupled with the press attention given to protesting artists like Skee Mask, Zenker, and Stangl ("I know that for one brief moment I was in the minds of Spotify executives," the latter reflects), shows that musicians and fans have the power to impact the way global corporations operate.

Wholly ethical consumption under capitalism is nigh on impossible, and Spotify is so entrenched in modern ways of engaging with music that many people struggle with the idea of boycotting it. But ultimately, the point of a boycott is that it's not supposed to be convenient. And as the leadership of streaming giants like Spotify funnel our monthly subscriptions into warfaring technology while paying paltry fees to artists, the onus is on the consumer to find out where their money is going and try to prevent it from being used violently.

"It's unlikely that Spotify will be broken up soon by any regulator, so we need to build alternatives," argues Stangl. "There's a huge amount of people who participate in music culture not because it's convenient but because it resonates so deeply with their way of living and how they want to express themselves. While we unlearn and deprogramme from Spotify, we need to understand that alternatives are possible."

Fred Garratt-Stanley is a freelance writer, follow him on Instagram