Features

Features

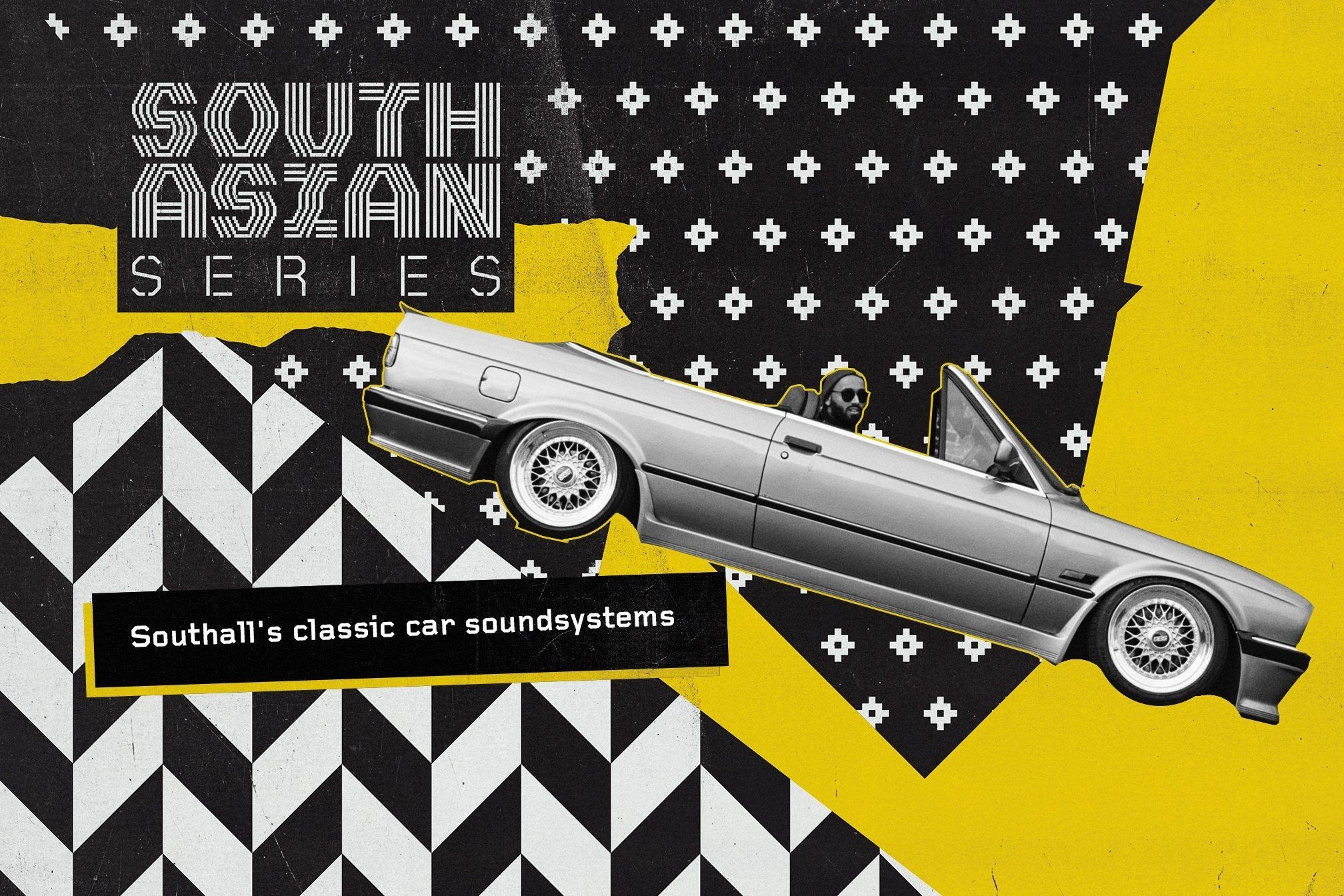

How classic cars and soundsystems connect Southall residents to their Indian roots

Ciaran Thapar spends an evening in London's 'Little India', where modified cars and dub reggae soundsystems carry messages of protest and connection to home across generations

The West London town of Southall has long been nicknamed ‘Little India’ on account of the many South Asian immigrants who settled there following the partition of the subcontinent in 1947. The town is a stronghold of diaspora; a mashup of business opportunity, community pride and lagging poverty; good food and bad driving; wedding outfits, industrial warehouses and A-roads. Being British-Punjabi is synonymous with having familial connections in Southall.

Throughout the 1990s, my paternal family would gather at my grandparents’ old home off Southall Broadway, whose terracotta wall my dad painted in his late-teens, 150 metres from the Hambrough Tavern, a pub which burned down in 1981 after being attacked by locals for hosting a punk gig attended by National Front skinheads. The fire is regarded as a symbolic victory of anti-racism; of Black Caribbean and South Asian unity, a pushback against the hostility and state violence of the Thatcherite era.

The terracotta wall of my old family home is the guardian to some of my fondest, most sensual childhood memories: my grandma shoving roti or mango pulp into my mouth, the bright firework lights and hybrid smells of gunpowder smoke mixed with cooking spices drifting by, like clouds, on Diwali.

Another memory is the shudder of subwoofers blaring bassy music out of the tinted windows of cars whizzing by. I’ve noticed it again on my recent visits. The archetype of the ‘boy racer’ kitting out and parading his car comes in many forms across the United Kingdom. It is easy to dismiss as adrenaline-charged, materialistic indulgence. But it is not quite that simple. In Southall, cars and the sounds playing from their speakers plug into a rich social history.

“The best way to soundcheck your car is by playing dub,” says Ranvir Singh Jagdev, or Rana, grinning and stroking his long beard. He adds that his two go-to dub songs for testing a soundsystem are ‘Seventh Seal’ by Sound Iration and ‘Rumours’ by Gregory Isaacs. We’re meeting on a late-summer’s evening in a back garden garage, which contains a soundsystem built from cut wood and makeshift speakers piled high towards the ceiling. The bass of dub reggae shakes the room via 7-inch vinyls spinning on a turntable, playing the music of legends like Tony Tuff and Sound Dimension, while we enjoy a game of pool and drink cold beers.

Rana, who is in his early-thirties, owns a grey E21, the coveted first generation of BMW 3 Series compact executive cars, produced between 1975-1983. Like many others in his community, alongside a lifelong fascination with classic BMWs he has also grown up listening to dub. One of his earliest memories is hearing ‘Report To Me’ by Gregory Isaacs on cassette. His intertwined passions for cars and music—which, for others in Southall and across the UK, branch out to brands like Mercedes-Benz and Volkswagen Golf, and genres like Bhangra, hip hop and UK garage—are inherited from previous generations of Sikh Punjabis. “I spent my summer holidays building boxes for my friends’ soundsystems. Southall is known for it. Bass culture is big for classic cars,” he continues.

Dub reggae is the main soundtrack to Southall’s iteration of the collectible car craze because of 20th-century British multiculturalism. Aside from practicality—its uniqueness as a low, bass-heavy genre that demonstrates the quality of a soundsystem—dub’s popularity arose out of the town’s racial politics throughout the 1970s and 1980s. The same can be said for places like Handsworth, in Birmingham, another shared hub of the Black Caribbean and South Asian life, and the geographical focus of John Akomfrah’s acclaimed 1986 documentary Handsworth Songs, filmed during the previous year's riots sparked by police mistreatment of Black communities.

“It started way before we were born,” Rana continues. “When the riots were happening, Indians and Black people were getting targeted. So they united.”

In June 1976 a Sikh teenager called Gurdip Singh Chaggar was the victim of an unprovoked murder by a group of white racists in Southall. Groups like the Southall Youth Movement organised to defend the local Black and Asian populations from employment discrimination, racist attacks and presumptive ‘sus laws’ upheld by police, in which anyone could be arrested on mere suspicion of committing a crime. Three years later, in 1979, a local campaigner called Blair Peach was killed, allegedly by police, while protesting a National Front election meeting at Southall town hall. A riot erupted—two years before British Caribbeans in Brixton, South London, would riot against yet more police violence—thus marking a historic moment for British race relations.

Out of the mobilisation, protests and social intermixing came a cross-pollination of music culture. Fundraising concerts with titles like ‘Southall Kids Are Innocent’ were organised. Reggae dances, held together by homemade soundsystems and an emerging generation of DJs and singers, became popular among communities of colour across the United Kingdom as a safe space of expression, peace and rebellion.

Misty in Roots, one of the most influential UK reggae bands ever, we’re birthed by this period of Southall’s history. They would perform at the Tudor Rose, one of the only Black-owned businesses in the area, a former cinema that used to show Bollywood films before it was turned into a thriving music venue. Its near closure in the summer of 2020 prompted a peaceful Black Lives Matter protest on the road outside.

“My uncles were running soundsystems from when I was a little boy. And I remember running into this exact garage and they were playing music on turntables,” remembers Taranvir, explaining how he first came across dub. Him and Rana note that it is the legendary Jah Shaka, one of the most influential soundsystem DJs in the world, who has sustained their love for the genre. They have, like many die-hard fans, seen him perform hundreds of times; a framed poster from a Shaka dance in Bristol in 1999 hangs proudly on the wall next to the pool table. “It was my first Shaka dance when I was 13 or 14-years-old that my uncles dragged me to. That was the turning point. I was there in the dance like: this is it, Shaka is king. We used to walk down to the Tudor Rose, because there were loads of reggae events there,” Taranvir continues.

Across the 1980s and 1990s, UK reggae music evolved with the success of artists like Aswad, Matumbi, UB40 and Maxi Priest, who popularised the sound in new stylistic directions. Meanwhile, the Bhangra scene grew across the UK, fusing traditional Punjabi folk music with thumping electronic hip hop production. Southall as an area was, of course, one of the genre’s incubators. Soon, artists began to combine it with the existing dub influence; Bhangra and dub were mixed into one another at Punjabi weddings, a fusion of tradition which continues to this day.

“You had some of the old school Bhangra music created with live instruments, and they don’t really have a bass guitar, just the kick of the drums to keep it flowing. But when you take a reggae bassline and mix it for a live audience you create something special,” says Taranvir. The sounds of two ethnic minority communities found a synergy. The earliest and most successful of these hybrid endeavours was producer Bally Sagoo’s 1992 album ‘Essential Ragga’, which boasted the combination of artists from the Caribbean and India singing authentically together, a sonic representation of a multicultural consciousness. Asian Dub Foundation rose to prominence over the same decade, initially by playing at anti-racism gigs.

Also playing pool with us is Inderdeep Ghatora, or Indy, who is 26. He owns a cirrusblau metallic BMW E30 from 1987, which makes it 34-years-old. It still has the heated seats from its original design.

“These cars are like time portals,” Indy chuckles, receiving nods of agreement from Taranvir and Rana. “They take you back to what it was like. The feel of the seats, the smell of the fabric, it’s still the same as it was back then.”

There are now hundreds, if not thousands, of classic BMWs stored in private garages and tucked under tarpaulin sheets in converted driveways on residential streets across Southall. In some families, multiple generations own them. For the mostly British-Punjabi collectors, many of whom know one another, having frequented the same handful of schools, gurdwaras and desi pubs, the old school BMW is a lifestyle; a glitzy, shrewd financial investment. But when dub music is playing, too, the classic car is also a nod to the struggles, resilience and lessons of the past.

“A lot of the conscious lyrics in dub speak about where we’ve come from, where we are now, how we want freedom,” says Taranvir passionately. He now runs an independent record label with Rana and Indy called Vedic Roots. They support dub artists from across the world to record, press and distribute their music. “From Punjab, from India, our colonial hurt from when we were ruled by the British. That has been handed down to us. The driving force of the music is an educational message that you can pass on from generation to generation. ”

Ciaran Thapar is a freelance writer and author of Cut Short: Youth Violence, Loss and Hope in the City, follow him on Twitter

Hark1karan is a community photographer capturing Punjabis, Sikhs and various aspects of London culture, check out his website and Instagram