Features

Features

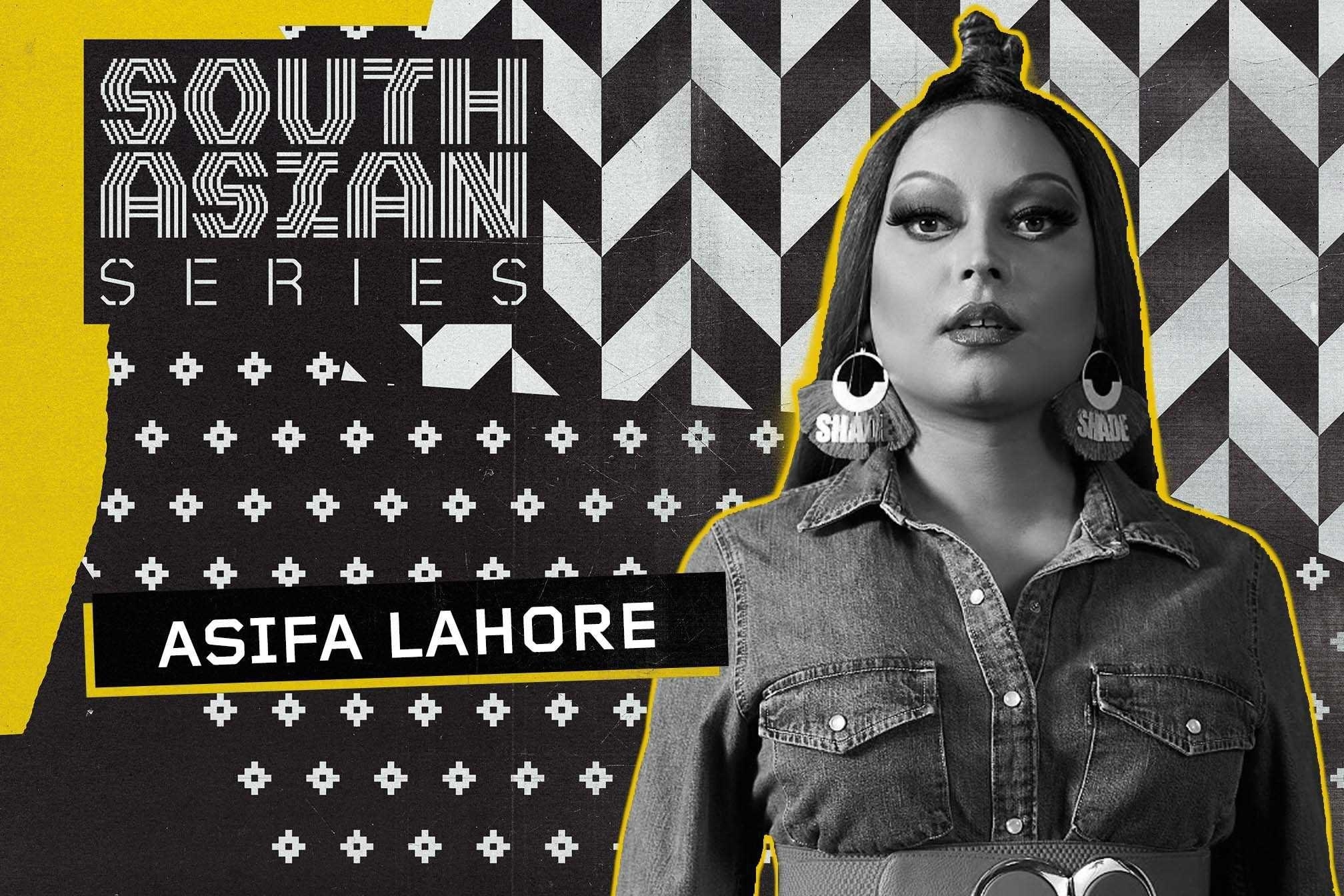

Britain's first out Muslim drag queen: Asifa Lahore is a proud clubland pioneer

Safi Bugel talks to Asifa Lahore about London's queer South Asian club history & navigating DJing and performing as a disabled, Muslim trans woman

Asifa Lahore was just 17 when she started clubbing, first frequenting the mainstream LGBTQ+ bars in Soho before finding a community of fellow queer South Asian partygoers elsewhere. Within the settings of Club Kali and Urban Desi, she was able to connect with people who looked like her and dance freely to the songs she grew up with. Here, Lahore also became acquainted with the Chutney Queen movement: a long lineage of South Asian drag artists who would traverse boundaries with their lip-synced performances to a mashup of Bollywood and UK pop hits.

After a decade on the scene, Lahore started her own career in drag, which became an avenue for her to explore her identity and channel her passion for performing. She’s since become a regular on the stages of the legendary events she came of age at, as well as at her own night Disco Rani. Adopting the title of ‘the first out Muslim drag queen’, Lahore’s stint on the circuit has allowed her to grow as both a person and an artist.

Still based in South London, Lahore speaks to Mixmag about the city’s queer South Asian club history and navigating drag as a disabled, Muslim trans woman.

When did you start going out clubbing?

I began clubbing when I was a teenager at Brit School. I would sneak out and tell my parents that I was going to extra, late-night college activities. For the first three years, I was heavily involved in central London and Soho which, in the early noughties and late 1990s, was definitely very much a white space. I'd very rarely see another South Asian person. There were a few Black people here and there, but hardly any South Asian or Middle Eastern people. It was only in the mid-noughties, around 2005 or 2006, that I discovered spaces like Club Kali in London.

I began going on my own, then I made friends and discovered support groups for South Asian LGBTQ+ people through the clubs and spaces that would just pop up. Here, I became aware of the Chutney Queen movement, which is South Asian drag that has been thriving for decades. The first time you go to a South Asian queer space as a South Asian person who identifies as queer, and you see so many Asian men, women, trans and non-binary people dancing around to all these songs that you've grown up with, in a camp manner, in a gay manner, in a safe space, and you see these drag queens also performing to the songs you've grown up with, it not only makes you feel safe but it blows your mind! It’s like, wow: here’s a community that I’m obviously part of that I never knew existed. I felt that I found my people.

I have very fond memories of dancing, watching the Chutney Queens perform, dancing along to Lata Mangeshkar and the hits of the ‘90s and noughties. It was an amazing space.

What other music was being played in these spaces?

Bollywood, bhangra, the chart toppers in the UK. It would go from a Mangeshkar song into an R&B song by Usher, into the latest Bollywood song, then a Pussycat Dolls song - it was all very intermixed. In the early noughties, when I began going to the clubs, Middle Eastern music and Asian music was really influencing the pop charts: you had Beyoncé, Truth Hurts, Aaliyah and all these sounds in R&B music that were so Bollywood. Panjabi MC, etcetera. So it was just a natural mix of music, both Eastern and Western, that blended really well.

You came of age watching the Chutney Queens on stage, but how did you get into drag?

I got into drag by total accident. I was out clubbing one day in Soho in 2011 and in one of the bars there was a poster for a completion called Drag Idol, a national cabaret competition that happens every year. My friends were like: you always wanted to perform and this is your chance. Whilst as a teenager I went to Brit School, I didn't pursue a career in the performing arts because I was always scared that I’d have to be open about my sexuality and who I was, but as a teenager I wasn't out. Fast forward to 27, I was out, I was already married to the love of my life— another Muslim guy— and it felt like the right time to pursue some performing again, for a little bit of fun. So I entered this competition wearing a rainbow burka, singing parody songs about being Asian and Muslim and queer. It started from there.

What did you think drag would bring to you?

I found it was a really accessible way to perform. Coming from a performing arts background, I was either too effeminate or too brown or too skinny for parts that I would audition for, so I think drag was a good way to perform in a style that I wanted. I essentially just wanted to sing, so for me it was an accessible way to do this without having a finger pointed: you need to do it this way or that way, you're not doing it right, etcetera. With drag, anything went. The accessibility I found to perform again is what drew me to it, as well as the glitz and glamour.

What was the response from your peers like?

It was very mixed. Like I said, I entered this competition and it was predominantly hosted at queer venues. The response was very mixed because half the audience was like “isn't this great, you've got a British Asian drag act being the stereotype and then breaking down the stereotype," and then you have the other half who either didn't get it or said a drag queen shouldn't be wearing a burka; it’s offensive to the queer community, to the Muslim community. I remember arguing with judging panels and saying: well, these are my experiences, I’m a queer Muslim. If I want to wear a rainbow burka, a black burka or a Union Jack burka, that's my prerogative. But what divided audiences and my peers actually got me to the grand final of that competition, and gave me the title of ‘Britain's first out muslim drag queen’. It also kickstarted my career, I began getting bookings. I owe a lot to that Drag Idol competition.

You took your drag act to queer South Asian clubs. What was that like?

After the competition was over, I began performing not only in mainstream queer spaces but also at LGBTQ+ Bollywood and bhangra club nights. I performed in spaces like Club Kali, Urban Desi and I also went on to open my own club night called Disco Rani in West London. As I said, I’d grown up watching the Chutney Queens perform to Bollywood, bhangra and pop songs of the time, so when I started DJing and performing in these spaces, I purposely mixed both my Western and Eastern influences. In the mainstream queer spaces, you had live singing and live drag acts, but in the Asian scene, everyone just lip-synced. What I did was sing and perform Bollywood songs live, bringing in a breath of fresh air; it went down a storm. The South Asian queer spaces gave me the chance to mash up different cultures and different things that really influenced me as a drag queen.

What was the environment like in these settings? Was there a strong sense of community?

Oh most definitely, there was a definite sense of community. It's a melting pot of different experiences around being queer and South Asian: you had people who were out, people who weren't out, people who were in marriages of conveniences, lavender marriages, people who were trying to find their way, people who were of an older generation, people of a younger generation. There were people from overseas, visiting, studying or asylum-seeking here in the UK so you wouldn't just get a British Asian experience, you'd get an experience from overseas, a sense of what was going on there too. I was part of this underground community for a number of years.

Have these spaces changed over the years?

It’s still a great space, it’s a space I’m still part of and it’s a huge part of my life. But it’s definitely changed over the last decade. More and more young people are coming out, not only to the scene but coming out as queer, as LGBTQ+, trans, non-binary. There's more of an emphasis on the fact that you can live your life how you want to live it. 10-15 years ago when I first started on the scene, the only thing you could hope for was to find a marriage of convenience, or coming out wasn't contemplated by a lot of young South Asian people from the queer background. But now, not only do these spaces have support systems and charities doing work within the community in regards to younger people coming out, you also see a lot of queer South Asian people out on the mainstream gay scene, much more than you did before.

A lot of it is also down to social media and the internet: 15 years ago, yes we had the internet, but social media was very much in its infancy. Now I think its much more easy to find people who look and sound like yourself, whether that's overseas or in the UK. Even within South Asian media in the last 10 years, there's been so many different flashes of queer beings in both films and dramas. Trans rights in Bangladesh and Pakistan are being explored in the media. There’s a lot that's been happening that has informed our psyche in the UK as well. That’s not to say that there isn't more work to be done, but it’s an exciting time to be South Asian and queer.

Did performing in these clubs help you take pride in your identity as a trans, Muslim woman?

Oh most definitely. Although I’d just go and dance the night away, I was dancing the night away to songs that I grew up to and watched on the screen. It's not like I could go to a straight Asian club and dance the way I want to dance to ‘Choli Ke Peeche’, for example. But in those spaces I could do. So when it came to doing drag, not only did it make me proud to be a trans person within the community, it also made me be proud of being a British South Asian queer person in the mainstream queer community. Wherever I go, I’m very proud of all my identities: it shows in my performances, it shows in the way I dress with my drag. I’m very inspired by Eastern fashions as well as Western fashions and mixing them together. So, yes, I think the scene has made me proud of myself and has allowed me to really harness the skills to be proud of myself outside of the scene as well.

You also identify as disabled, how do you navigate having a disability with performing?

I’m on the blind spectrum: I’m registered blind and I suffer from retinitis pigmentosa, which is a rare eye condition but oddly enough its quite common in South Asian countries. I have learned skills to cope over the years. The older I’ve got, the worse my eyesight has got; when I was younger, I navigated fine, but since I hit my 30s, when my drag career really took off, there are times when I’m out in the club or out in the venues performing and I can't see the audiences’ faces. All I can see is shadows and I can hear them, so in my mind I have to pretend a lot of the time that the people are smiling, that it’s going well. I learn how to react to an audience.

When I’m moving around in the club, the lack of lighting can be very frustrating to me as a blind person. It’s weird because I can tell who somebody is in front of me only by their body silhouette. If it’s dim lighting, I definitely don't see them. It got to a point where, because people didn't know that I was disabled, they would get really offended that I wasn't talking to them or making the effort. So a lot of the ownership and skills around me being disabled came when I began being honest about my disability. Realistically, I’ve only really been honest about my disability in the last three years or so.

As a disabled person coming from an Asian background, it’s very hard because I’ve grown up with issues of ‘black magic’, being cursed as an explanation of why I am how I am. Disability in the South Asian context isn't really discussed, so I learnt to keep my disability to myself and just wing it and fake it. But three years ago, it got to the point where I began being honest about it. I think because of all my other identities, my disability was put on the back burner: being queer, being trans, being South Asian. So once I had dealt with all of that, I finally dealt with being disabled.

Now I have a support worker who helps me a lot, audiences know I’m disabled and whenever I go into new venues I always do risk assessments so I know where the stage is. I work with my disability rather than working against it - that has really helped me more than anything ever. It’s another identity to hold and be proud of.

How has your drag act changed since you started?

I think it's become much more refined. What started off as a little bit of a joke and a little bit of fun is now a refined character. When I’m in drag, it’s very much an alter ego: I put on this British Asian stereotype who's very sexy and naughty, she pushes boundaries. She is the stereotype but she breaks down the stereotype on what it is to be a British Asian who is queer. She’s also much more refined in her looks, in the songs she does, in her vocals, the dancing. I think that’s also a part of the fact that over the last decade, not only has my drag act grown, I’ve also grown as a person. Living life as a gay man and then transitioning four years ago during the height of my drag career, going through those things personally and with my family, reconciling with my family in Pakistan, going back to Pakistan after a period where I wasn't going because I was scared: I think that's also influenced me as a person. I’m very confident of who I am, I'm in a happy space and I think my career, my drag act, who she is, is in a very happy space too. This month, for example, I’m hosting and performing at Reading Pride, Surrey Pride, Birmingham Pride; that's without platforms like Drag Race UK, for example. I’m in a really happy place.

You've enjoyed a long and rewarding stint in LGBTQ+ clubs as both a partygoer and a performer, but what has the queer scene got left to do?

I think South Asian queer spaces have been hit almost ten-fold across the pandemic. With venues being crumbled and everything, we're finding it hard to bounce back. The queer community has a history of racism, and in the last few years, I think racism has really been in the spotlight. Queer South Asian spaces need to be supported, now more than ever. Otherwise they will vanish. So, I think the queer community on the whole needs to do more.