Features

Features

Come on, feel the Japanoise

As Halloween approaches, Adam Wright looks back at the terrifying sound and history of one of the most extreme genres to ever exist

What comes to mind when you think of Japan? Chances are it’s something elegant and refined, perhaps a beautifully embroidered kimono or cherry blossoms falling gently from a tree with Mount Fuji in the background. Whatever it is, chances are it’s not the most brutal, violent and completely batshit crazy genre of music to ever have existed.

But Japan is, of course, the birthplace of Japanoise. An obvious portmanteau of “Japan” and “noise”, the key to understanding the genre is right there in the title: noise - sheer, bloody, gruesome, insane noise - strangled out of mangled electronics, screaming feedback, power tools and extreme amplification. And it’s all served up by a cast of freaks and lunatics who look like they stepped out of a Junji Ito manga or a horror movie directed by Takashi Miike.

In the realm of extreme music, not much comes close to Japanoise in terms of pure extremity, perhaps apart from some fringe areas of metal (such as grindcore) or the intense electronic sounds of extratone, which pushes BPMs up to 15,000 and as high as 1.2 million (yes you read that right: 1.2 million beats per minute).

Noise music existed before Japanoise became a thing, but just as it has done countless times before - with everything from automobiles to animation - Japan took a foreign idea, pushed it to the limit and perfected it. As music writer Paul Hegarty put it: “It only makes sense to talk of noise music since the advent of various types of noise produced in Japanese music … With the vast growth of Japanese noise, finally, noise music becomes a genre."

Usually completely free of melody or even structure, Japanoise has been described as a movement that was completely opposed to music, or even as the end of music itself. Your mum probably wouldn’t even recognise it as music - and the listening experience is as physical as it is aural.

David Novak, Associate Professor of Music at the University of California and author of Japanoise: Music at the Edge of Circulation, says: “Talking with noise listeners, I heard that feeling described a lot. When asked ‘How does this recording sound?’, people would relate their physical response when listening. ‘I felt my teeth were crunching’; they tell us something about their body reacting to sound. It was more as if they were describing being electrocuted than being in a dialogue with an artwork.”

The sound emerged from Japan’s punk scene and enjoyed its peak from the early 1980s to mid-1990s with artists such as Incapacitants, C.C.C.C. and Hijōkaidan. Its best-known exponents are without doubt Merzbow and Hanatarash - but more on them later.

Read this next: Curious Gorge: Japan's idiosyncratic musical movement celebrating 10 years of existence

The roots of noise music can be traced back more than 100 years, essentially making it a byproduct of the industrial revolution. Its basic ideas first took shape in the Art of Noises manifesto written in 1913 by Italian Futurist artist Luigi Russolo, who observed: “Ancient life was all silence. In the 19th century, with the invention of the machine, noise was born. Today, noise triumphs and reigns supreme over the sensibility of men.”

Along the way, experiments with noise were conducted by the Surrealist precursors the Dadaists (most notably their Anti-Symphony concert in Berlin in 1919), the musique concrete movement using found sounds that started in France in the 1940s, the Japanese sound art collective Group Ongaku in the late 1950s, and the revolutionary Fluxus artists in the US in the ‘60s, whose notable members included Yoko Ono.

But noise music’s breakout moment came in 1975 when ex-Velvet Underground frontman Lou Reed released ‘Metal Machine Music’. The double album is more than 100 minutes of modulated feedback and guitar effects, contains no songs, melody or traditional structure, and was pulled from stores by a seriously pissed-off RCA Records three weeks after it was released.

It’s still not known whether Reed was playing an elaborate joke on the music industry, whether he was trying to get out of making more albums for RCA, or whether he was actually serious, but whatever it was, ‘Metal Machine Music’ would soon come to influence the Japanoise movement.

In Japan, the punk scene was starting to disintegrate in the late 1970s and moving in a more anarchic, noisy direction mainly thanks to Hijōkaidan — widely credited as the first true Japanoise band.

Originally a fairly traditional punk outfit, Hijōkaidan brought in influences from the industrial and avant-garde scenes of the 70s, injected harsh noise into their music and developed a violent, confrontational stage show that would soon become a hallmark of the genre.

Read this next: 8 up-and-coming Japanese DJs that you need to know

In the early 80s, Hijokaidan’s first recordings found their way into the hands of a Tokyo man named Masami Akita, who had already fallen under the spell of Reed’s ‘Metal Machine Music’. These combined influences inspired him to start making music, and his first recordings were released in 1981 under the title 'Metal Acoustic Music'.

The album has gone down in history as the first of a now staggering 400 albums released by the artist known as Merzbow.

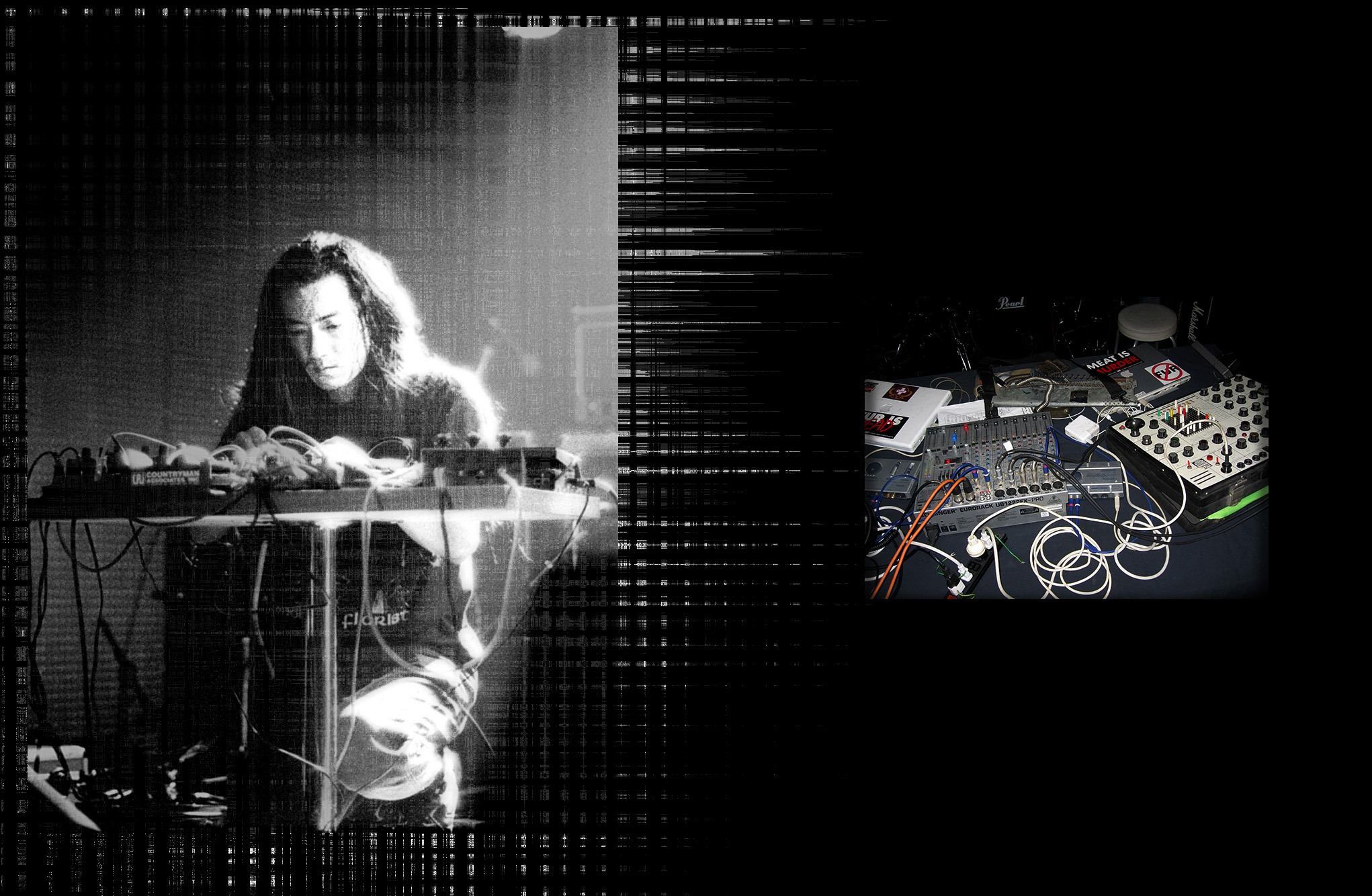

With an intense persona, an overt interest in Japanese bondage and a firm belief in animal liberation “by any means necessary”, Merzbow is regarded as the godfather of Japanoise, and also one of the most prolific artists of all time.

Here’s how the art magazine Lightworks described his sound in 1985: “Imagine being surrounded in hot, molten electronic/industrial noise…harsh edges giving way to a deep bass deluge of sound. It pours out and into you...this music could be how you feel three seconds into a Space Shuttle lift-off. Surging intense, at the outer limits of control and lack thereof.”

Over his 400-odd albums, Merzbow’s brand of harsh, confrontational noise has explored various nuances, including relatively accessible drone-based ambient works (‘Vibractance’) through to albums that could soundtrack the apocalypse (‘Venerology’). But arguably his best-known album is the extreme 1996 release ‘Pulse Demon’ — 76 minutes of pure, unfettered white noise mastered at maximum levels which one listener described as “like being set on fire”.

In 1984, Merzbow released a split cassette with some noisy newcomers named Yamantaka Eye and Tabata Mitsuru, who would eventually come to eclipse him in terms of pure extremity.

Initially recording under the band name The Hanatarashi (meaning “snot-nosed” or “sniveller” in Japanese), they soon changed their name to Hanatarash — a name that is now etched in music history as the most dangerous band to have ever existed.

Hanatarash was formed in Osaka in 1982 after Eye and Tabata met while working as stage hands at a Japanese concert by German industrial music pioneers Einstürzende Neubauten. Like Merzbow, the Hanatarash guys had been on the fringe of Japan’s punk movement in the late 1970s but felt that the scene had lost its edge.

They decided the way forward involved combining the energy and intensity of punk with the destructiveness and industrial performance art of Neubauten, and turning everything up to 11 and beyond.

Read this next: Selective Sounds: our picks for the most high-energy mixes of 2023 so far

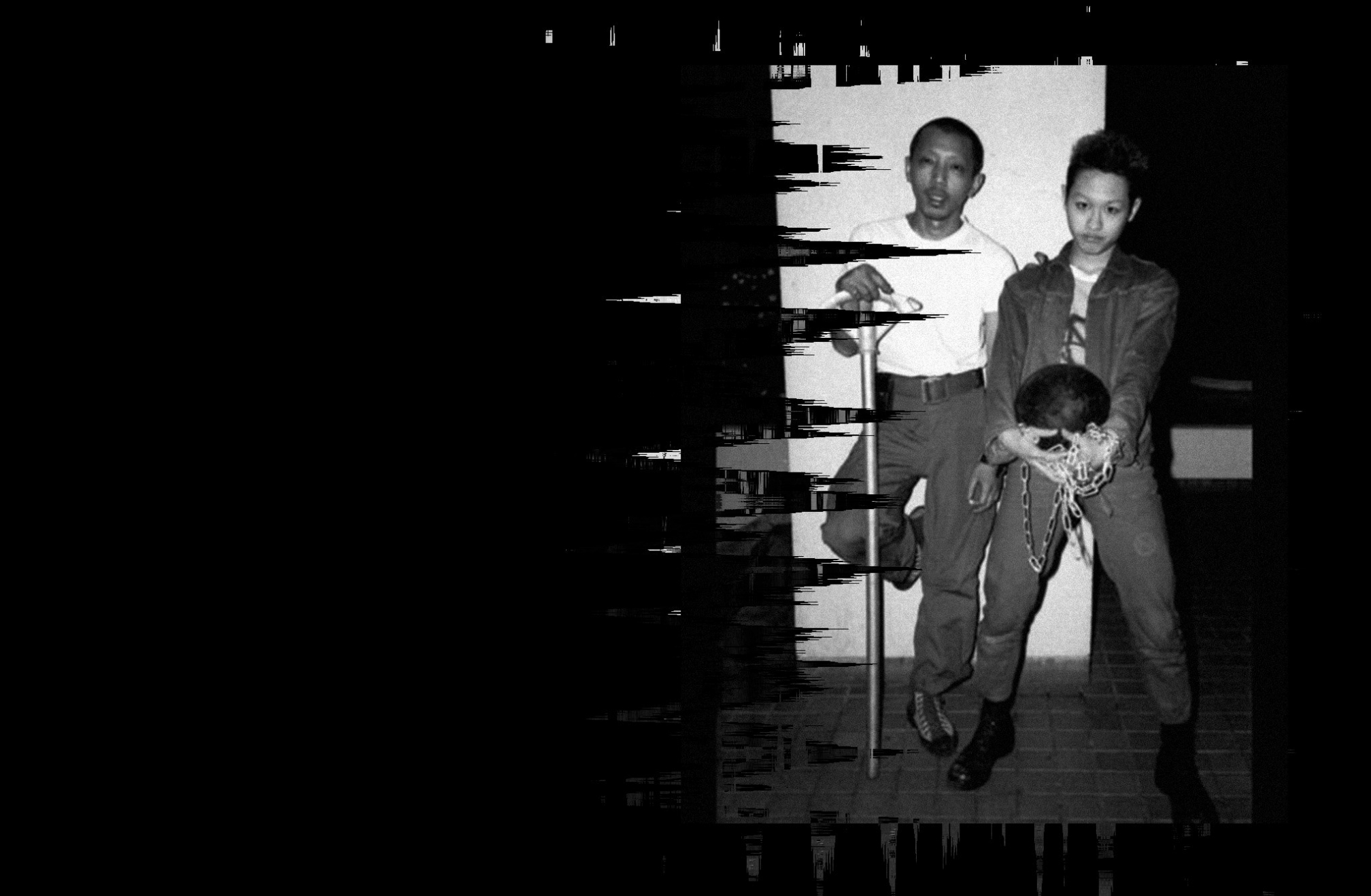

Their recordings from the early 80s — imagine screaming feedback, pulsating, atonal electronics and heavily processed vocals — are bombastically mental, but still don’t capture the pure, violent insanity of their live shows.

Huge sheets of glass were often thrown into the crowd and smashed over the heads of audience members. Eye once brought a dead cat on stage and cut it in half with a machete. During one gig, he came out with an amplified power saw strapped to his back, and almost severed his leg when it came loose and cut through his flesh.

By 1985, audience members were required to sign waivers before entering Hanatarash’s live shows, and fans expected a certain amount of mayhem - but a gig that year at Tokyo’s Super Loft venue went further than anyone could have expected.

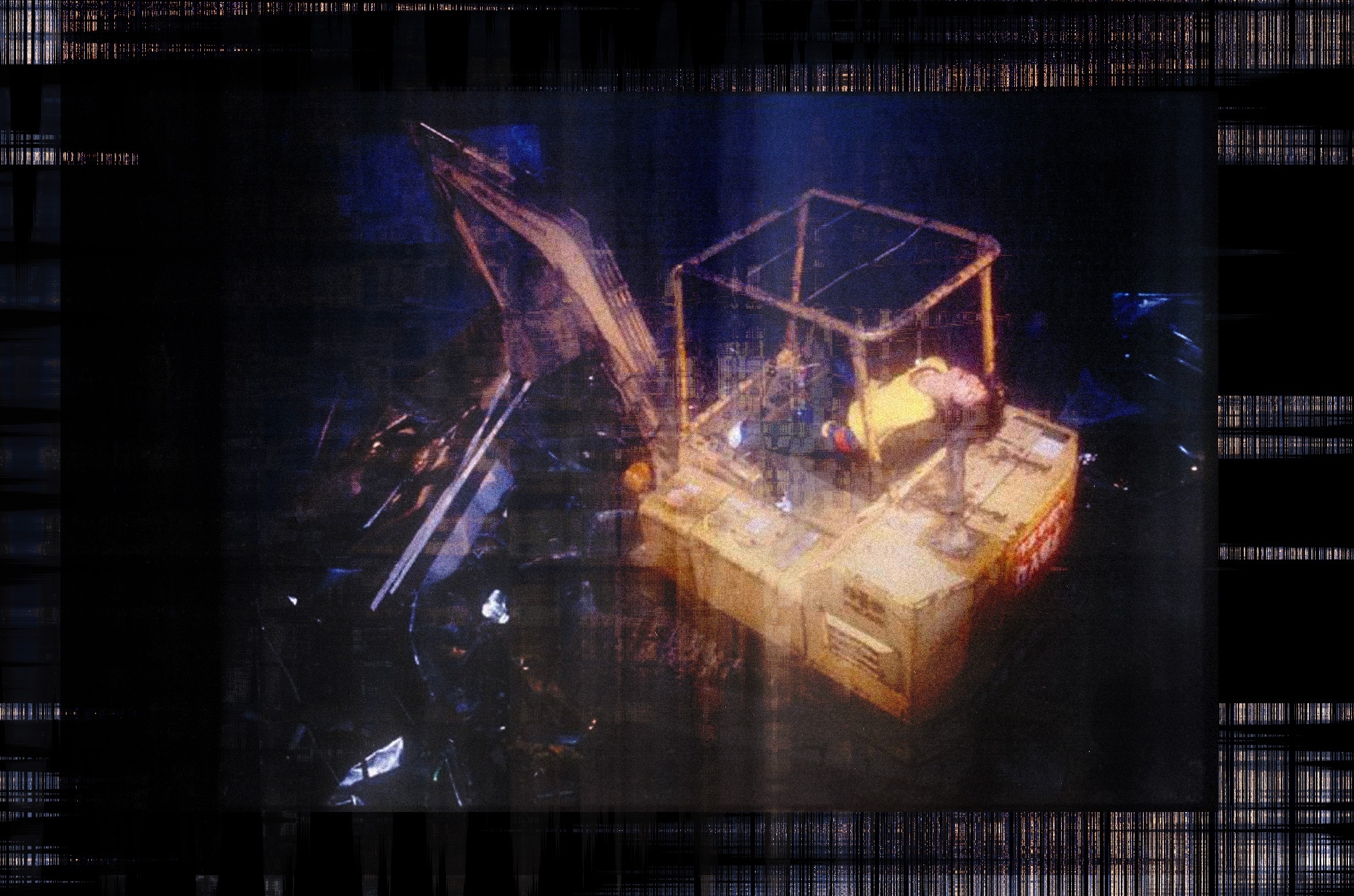

Mid-show, Eye left the stage and went outside to start up a Komatsu excavator, drove it through the back wall of the venue and onto the stage, trashed as much of the venue as he could with the huge piece of heavy machinery, and finally pulled out a Molotov cocktail, intending to burn the club to the ground.

Even their fans had had enough at this point. Eye was physically restrained by the audience, the show was brought to a halt and Hanatarash was banned from performing live in Japan. It’s a miracle that no one was killed.

Hanatarash was only allowed to return to live performances in Japan in the mid-1990s after Eye promised to behave himself. But by that stage performance the Hanatarash project — and Japanoise as a scene in general — was on the wane, and Eye and Tabata were more focused on their next band.

Read this next: Harder, better, faster, stronger: has dance music got harder and faster?

Boredoms started out as a harsh, dissonant noise-rock band, and even toured with alt-rock giants Sonic Youth and Nirvana, but over the years they mellowed out with excursions into sweeping electronica, psychedelic space rock, and hypnotic tribal percussion performances. They are still considered to be active but have not performed live since 2015.

Apart from the alt-rock scene, Japanoise also had a significant impact on electronic music even though many of the acts rejected the idea that they were electronic musicians.

Novak pointed out that despite using electronic equipment in their recordings and live shows, many Japanoise artists intentionally only gained a rudimentary understanding of the tech and weren’t really interested in knowing how it worked; “Technology was generally perceived as a source of dehumanising violence that art must resist, even as people inevitably absorbed its effects.”

Today, of all the classic Japanoise artists, only Merzbow and Hijōkaidan continue to release music, but the movement’s influences live on, particularly in electronic genres such as industrial techno, dark ambient and power electronics.

None of those artists are likely to destroy the venues they are playing at with an excavator, but the impact of Japanoise will continue to reverberate loudly in the eardrums of generations to come.

Adam Wright is a freelance music and entertainment writer. Follow him on Instagram here.