Features

Features

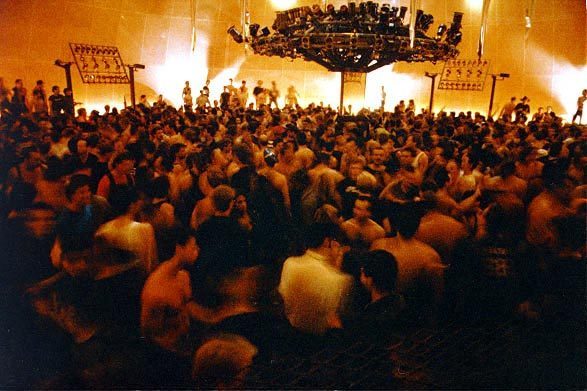

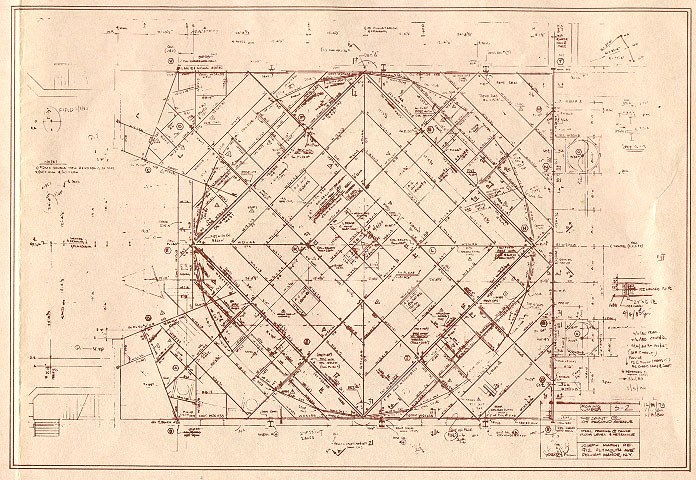

An exploration of the evolution of nightclub architecture since the 1960s

John Leo Gillen’s new book, Temporary Pleasure, looks at some of dance music’s most important scenes and their various design codes

During the ‘90s, as John Leo Gillen was growing up as a child in the West of Ireland, he would visit his family’s business while they worked. It was a nightclub, and on weekends before the dancers filled its floors, drinks flowed from the bar and music pumped from its soundsystem, he and his siblings would run around the empty space and explore its various nooks and crannies.

“We used to sleep in the cloakroom while they were working,” Gillen says. “A nightclub in the day, it’s a strange place. I have such strong memories of that smell – you could smoke inside at the time and there was also carpets everywhere so your feet would get stuck to the ground as you were walking around – it was kind of like a weird dirty playground.”

But it was being around their parents working, and eventually getting his hands dirty, that Gillen started to gain a real appreciation of the unique space his family had, and what it took to keep it going. “I worked in the club from when I was like 14 or 15, and we were always doing small alterations or big renovations,” he says. “So I was always really interested, but didn’t know it was architecture, we just had to figure out what we had to do with it next.”

Read this next: Intimate, nostalgic ‘90s party shots from the infant days of techno

Ever since, he’s been working in the nightlife industry across Europe. From his time in the family club, contributing to festival builds, to organising and constructing underground parties, Gillen has been immersing himself deep in the world of dance music design and production. His love for it would eventually lead to him studying for a master’s degree in Ephemeral Architecture and Temporary Spaces at Elisava, School of Design and Engineering in Barcelona.

It was during this period of studying, which he did much of in 2020 amid the pandemic shutdown of clubs, that he began formulating his project Temporary Pleasure. Exploring the fleeting nature of nightlife spaces, the in-the-moment temporality of the dancefloor, it is now a fully-fledged debut monograph that was published on April 25 via Prestel Publishing. “I was thinking about how all the clubs had disappeared,” Gillen explains of how the project started and came to grow. “And how there was going to have to be another reimagining of them afterwards – [so I thought about] how we can learn from what’s come before, what’s gone wrong and what’s been done right.”

The book explores the history of these ephemeral spaces in club culture. Told through key venues in important cities and moments across dance music history, it examines the rise of localised scenes and clubs, their distinct designs and architecture – as well as their shifts and demises as tastes, clientele and cities evolve. “Club movements are born as causes, in DIY spaces, created out of necessity by marginalised peoples,” Gillen writes in its introduction. “This often involves some form of ‘hack’ or new model, quickly inspiring copycats and triggering the process of commercialisation.”

Read this next: 50+ hours of dance music films to binge-watch

Moving through radical, student-led nightlife spaces in ‘60s Italy; New York’s heyday of disco at the Paradise Garage, Studio 54 and more; Chicago and Detroit at the genesis of house and techno; the rise of Ibiza's superclubs from the ‘70s to the ’90s; acid house and the UK’s free party scene, and much more – Temporary Pleasure covers a diverse array of dancefloors, and their distinct design languages, where thousands have shared special moment down the decades. Spaces lost to the annals of time, such as Manchester’s The Haçienda, Berlin’s ex-electrical substation e-werk and Chicago’s The Warehouse are represented, as well as those that have stood its test including London’s fabric and Ibiza’s Amnesia.

While covering a broad scope, Gillen by no means intends it to be a definitive history of club spaces. “There’s definitely a Western bias – there’s a lot of US scenes and a lot of European scenes and not a lot outside that,” he explains. “It was dependent on stuff that I was familiar with and already interested in or knew the music that was associated with it – and it was also really dependent on someone having documented it, and a lot of the clubs just aren’t documented.”

Part of his research process included conducting interviews with key people from those eras, such as Ben Kelly of The Haçienda and Dimitri Hegemann of Tresor Berlin. “They were all really interesting,” Gillen says. “It’s one thing to research through the Internet, or through books or photos, but it’s another thing to actually speak to somebody who was actually there – so much has become mythologised over time, so one insignificant detail can become the whole identity of this club or place.”

Perhaps most importantly though, as Gillen set out to understand when he first began the project, is that the book also helps to frame the present and future of dance music spaces. One chapter looks at ‘Post-Club’ in the 21st Century, which looks at new, temporary spaces dance music has come to occupy as the superclub’s relevance began to wane, festivals exploded and city development projects began to pick up speed at a lightning fast rate. Manchester’s The Warehouse Project – a constantly moving mini-festival; Glastonbury’s five-nights-a-year queer club The NYC Downlow; Amsterdam’s legendary Trouw; and Brussels’s music festival slash art and architecture celebration Horst are all contextualised – presenting the ever-evolving landscape of nightlife design, architecture and temporary spaces.

Read this next: Tresor 31 explores techno as an artistic and social movement since the fall of the Berlin Wall

But following a global, near-complete shutdown of clubs, festivals raves across the world as the COVID-19 pandemic hit, and now within a shaky economic climate and the cost of living crisis – even the Post-Club chapter feels as if its age has passed its apex, like the other scenes featured in the book. So what comes next? “I just see it moving away from these bricks and mortar, purpose built spaces,” Gillen says. “And just bring in something a bit more fluid like temporary and transient spaces, hybrid spaces.”

One interview with Karim Khelil of architecture collective Assemble Studio presents an optimistic picture, despite the industry’s current struggles. “Nothing lasts forever, even the death of club spaces,” he tells Gillen. “As long as memories are preserved and the passion continues, I feel that the clubbing experience will exist in one form or another.”

Temporary Pleasure by John Leo Gillen is published by Prestel

Isaac Muk is Mixmag's Digital Intern, follow him on Twitter