Features

Features

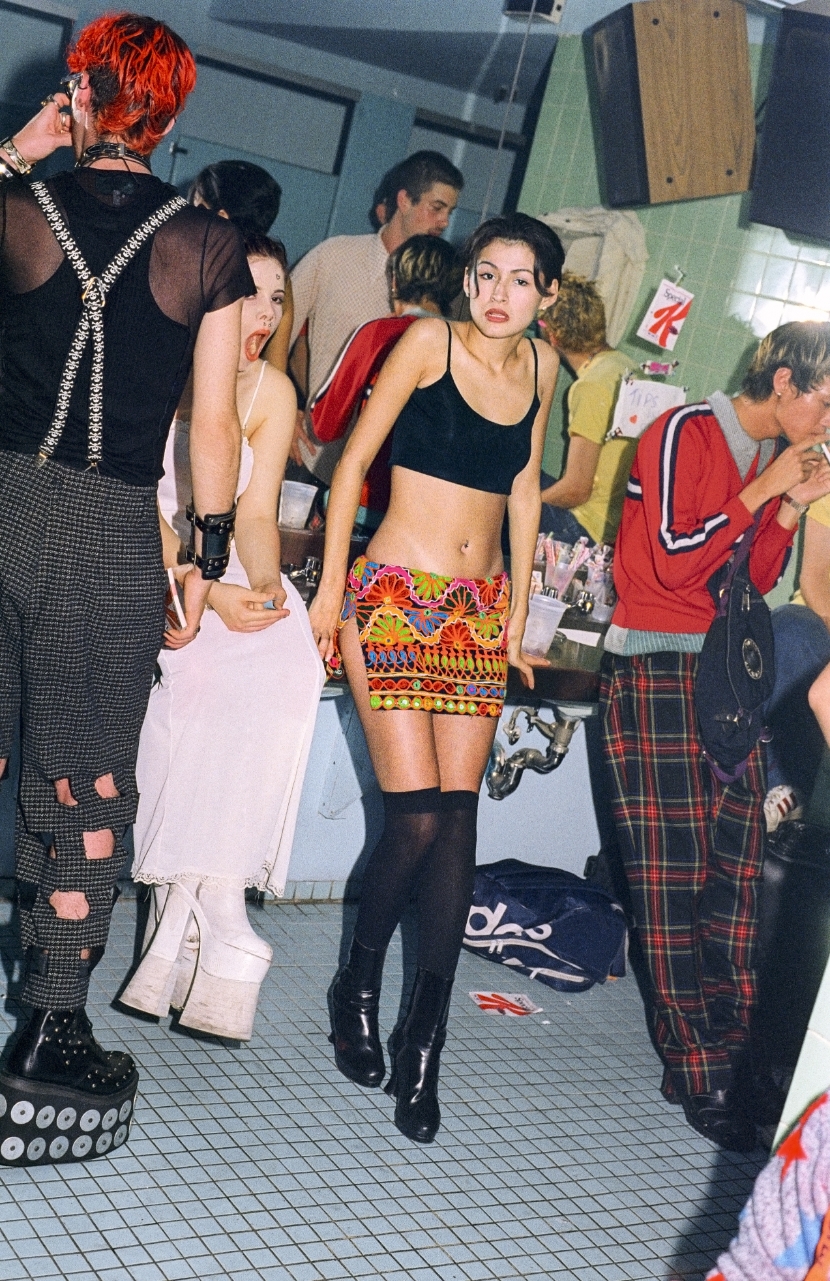

Intimate, nostalgic ‘90s party shots from the infant days of techno

From Berlin to New York, photographer Werner Amann spent much of his weekends in the ‘90s travelling from party to party capturing the euphoric highs and tired lows of a night out

In 1988, when a young Werner Amann was fresh out of school in small town Bavaria in Southern Germany, he took a low-key city break to the UK’s capital city of London. He had been to some small-scale “dance parties” in his hometown, but among the city’s ex-industrial estates he found a new sound that was burgeoning among the warehouses and fields around the M25.

“I brought my camera [to the UK], but didn’t photograph at warehouse parties,” he says. “But that was maybe my first real encounter with acid house.”

Attracted to the energy, he would soon find himself regularly at parties during his weekends. But having started photography studies after moving to Berlin, he would bring along his camera, where he would take portraits of clubbers in all states from dancing, smoking cigarettes, weary ravers asleep in a dark corner, to even a fresh faced Richie Hawtin spinning vinyl in 1994.

Attending parties predominantly in Berlin, frequenting now-legendary techno spots like E-Werk, Tresor and the annual Love Parade, Amann would also travel out of town to other parts of Germany and beyond – partying at the likes of Mayday in Dortmund, Omen in Frankfurt, underground parties in North-Rhine Westphalia, Limelight and Sound Factory in New York, to parades in Zürich and Paris.

Read this next: Rave the Planet brought back the original Love Parade spirit back to Berlin

Now, digging out images from an extensive archive of thousands and thousands of shots, a number of his pictures are collated in his new photobook Kein Morgen. The book’s name translates roughly to English as “without tomorrow” – a nod to the in-the-moment, forget-all-else state of mind of a night out partying. “Just being in the here and now and experiencing that with other people,” Amann explains, of what was so enticing about the scene. “There was a certain freshness – techno and other dance music was still relatively new and provocative, and the photographic possibility to document it attracted me.”

Nowadays in many spots in Berlin, but also a growing number of underground venues across the world, photography is banned inside the club. But in the early ‘90s, it was common to have people wandering the dancefloors taking pictures. “I was seldom alone with a camera,” Amann says. “In many instances, there were several photographers – looking back now you could say that it was a fresh and innocent time in [the early ‘90s], but techno and rave was already pretty big and also a bit of a media event.

Following the fall of the Berlin wall in 1989, and the reunification of East and West Berlin, techno exploded in the city’s underground nightlife culture, as an expression of freedom and unity, following years of a giant physical divider running through the heart of the city. “I had the feeling that I could document something very special and also something meaningful and historic,” Amann says. “Especially with how the techno scene developed in Berlin – it was this parallel with the post-Wall period.”

Read this next: Tresor 31 explores techno as an artistic and social movement since the fall of the Berlin Wall

Through capturing the early doors, anticipatory stages of a party, to the smoking areas and the afterparties – Amann’s pictures explore in up-close-and-personal detail the euphoric highs and tired lows of a night out. Exploring these heightened emotions that a long, sleep-deprived evening particularly appealed to Amann. “You see people in various states of ecstasy, loneliness to connectedness, boredom,” he explains. “A club or a rave is a very concentrated, condensed space where you can live out all these purely human emotions.”

The book also shows off the distinctive, yet interconnected aesthetics and styles of techno culture across the world, from the kink-influenced leather of Berlin, to the more colourful fashion of New York. In the end, the parties were places where people could simply express themselves. “I think there’s more places these days where you can express yourself with any kind of clothes you’re wearing,” Amann says. “But at that time a club was one of the few places where you could just wear anything.

“A club or a rave, it was like a positive utopia, where all kinds of people could come together,” he continues. “And it was a very special place, where you could find all kinds of different people coming together and escaping the greyness of life around it.”

Kein Morgen by Werner Amann is published by Spector Books

Isaac Muk is Mixmag's Digital Intern, follow him on Twitter