Features

Features

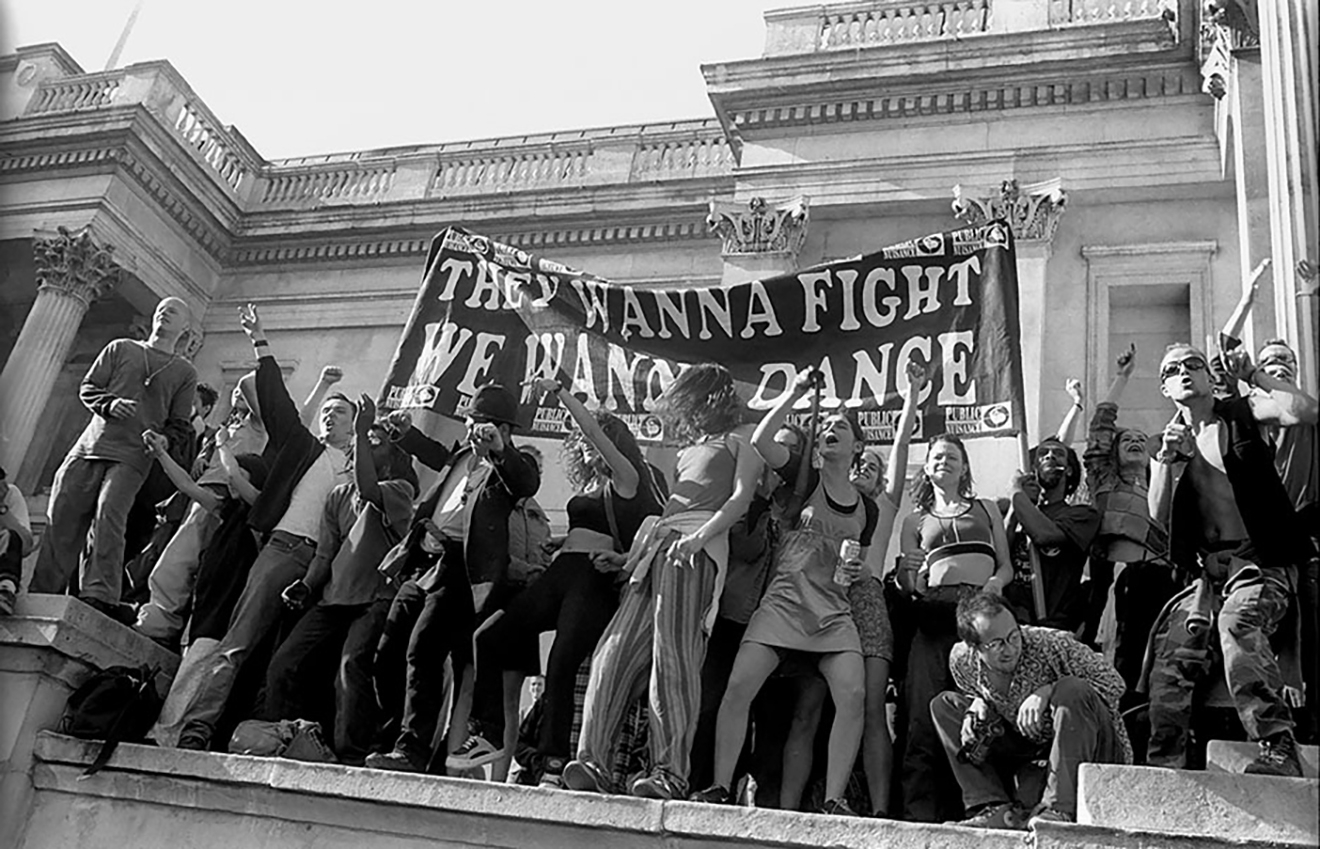

How partying became protest: Matthew Smith's rave photography documents the loss of freedom

With an update to his social history book Exist To Resist, Matthew Smith is shining a light on government oppression and the need for resistance

Free party culture started as a celebratory act of communion around rave music and soundsystems. When the British government and its police forces sought to crack down on this exercising of freedom, raves came to represent resistance.

That history is documented in the book Exist To Resist by photographer Matthew Smith, AKA mattko. He's been on the frontlines of DIY culture since the '80s, and from the Criminal Justice Act of the '90s through to the recent Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill, his work is a sharp and insightful documentation of partying, protest and lost freedom. “Photography has the power to show people the recent past in order to judge how the future is evolving,” says Smith.

Smith is currently crowdfunding a second edition of Exist To Resist, expanding on the social history book, initially released in 2017, with newly discovered images from his archive - thought lost for 20 years - and fresh research into public activism and the 'Kill the Bill' generation.

We spoke to Smith about the new book and his Kickstarter campaign. Pledge your support here and read his thoughts below.

Why do you think rave and protest culture go hand in hand?

It’s been like that since government in its lack of wisdom decided to make outlaws of us all in the 90s. Back then we were pioneers of the noisy protest which has been the subject of their more recent hate campaign against any kind of celebratory opposition to their failure.

Prior to the Criminal Justice Act protests in 1994 it was a fairly simple process for the state to co-opt demonstrations into violent confrontation. When we first allied dance music and protest during those events it became a lot harder to engineer conflict in such situations.

Since then rave has become the embedded soundtrack to effective public opposition to government and people have learned a more sophisticated approach to non-violent direct action. If they hadn’t legislated having a good time into a crime perhaps that might not have happened. But they did and it has. The police moaned about the presence of large mobile soundsystems on those demonstrations for very obvious reasons.

It doesn’t look good to be seen whacking a bunch of people hugging and throwing shapes to the music because that isn’t the confrontational violent behaviour they need as an excuse to wade in. Raving your protest just isn’t cricket for the powers that be. When you’re whooping and waiting for the bass to drop, you’re not the slightest bit interested in causing a breach of the peace, you just want to send it and make your voice heard in the dance.

Read this next: 37 photos from Tresor 31 Exhibition: Techno, Berlin und die große Freiheit

In your experiencing photographs raves in the '90s and today, what are the similarities and differences?

There’s a lot more hi-vis and heras fencing? There was a time back in the day when it estimated that roughly two million people were going out to free parties each and every weekend. Everything felt a lot more simple back then. You had to rely on your own ingenuity to find places, not your phone. People were not a product of their Instagram profiles. People with cameras like me were rare and not everywhere. The digital infrastructure of surveillance and oppression that we have now hadn’t yet been developed.

In many ways raving is just the same now as it always was. But everything evolves, nothing is static. Record boxes have been replaced by USB sticks. 1210’s gave ay to CDJs. Speakers, amp racks and generators once would have taken a couple of 7.5 tonne trucks to transport would probably fit into your average Sprinter. But saying that portable personal speakers are literally everywhere.

There are clearly massive differences. But for time immemorial it has been part of human condition to dance and celebrate together. That hasn’t changed.

Are there connecting aims and trends across the generations?

I have no idea. I’m just me and I can’t speak for everyone. For me it has always been about creating spaces where music, people, art and self-expression can intersect to create collective community, inclusive exhilaration and euphoria.

You've dedicated your work to covering British counterculture - why do you think it's important to document these movements?

Culture is culture. It only becomes counter when somebody wants to control it for their own nefarious purposes. Right now, I think government is the new counterculture because they clearly want to destroy the future security and quality of life that most people have come to take for granted. I started making images of my culture because it was being demonised by lies spread by the mainstream media and government of the time. So I worked to both perpetuate and celebrate everything that was good about it in as many ways as I could. The documentation is what’s left over from that process, which is why it is art.

I began making the digital archive of my film work over 10 years ago. When I first started publishing the images on my social media the biggest feedback from the public was “Look how much freedom we have lost in the space of a generation.” I have kept that idea in my mind ever since. Photography has the power to show people the recent past in order to judge how the future is evolving. Exist To Resist works on that very basic level. It is not about nostalgia. It’s about wake the fuck up and realise that you can do something about the toxic corruption that is masquerading right now as our so called leadership.

Back then we felt it was our civic duty to stand up for what we thought was right. Surely that is part of any real democracy? Recent legislation has been directly aimed at criminalising anyone who decides to do that. Law is not supposed to be a protectionist tool in the hands of those who manufacture it. But that is what it has become.

Listening to entitled uber wealthy corporate profiteers droning on about service to their country when the reality is that they serve only their own organisation at the expense of the country is just the height of hypocrisy. Part of the motivation to create a second edition of Exist To Resist is facilitate public debate about issues like that.

Read this next: Rave photographer Matt Smith: “It’s about documenting what people bring to the party”

Plus, right now in Bristol, there are a whole bunch of young people incarcerated on a three to five stretch as political prisoners of a sacked Home Secretary, who demanded their heads on spikes for daring to declare their displeasure at her fascist laws. That needs talking about. It’s not big. It’s not clever. But it’s definitely pretty ugly. And very, very annoying.

The Conservative party are not a political inevitability that we have to put up with forever. They’ve had their time. They’ve made their fortunes. Their greed and failure are self-evident. We need to evolve new methodologies in the administration of democracy that are actually fit for purpose outside of the tired, out-dated old right-wing left-wing paradigm.

What updates and changes does the second edition of the book include?

The new remix of Exist To Resist will have 20 extra pages, giving it a whopping 244 page count. The writing will be expanded to combine new knowledge about the times I lived through gleaned from research, folk history and information that has come to light via public enquiries such as the Mitting Enquiry.

Last year five rolls of film that had disappeared for 20 years turned up out of the blue. They will form the new image content for the second edition. All the way back then I gave them to a designer who was working on a music project for a chap called Guy Hatfield and Leeroy from The Prodigy called We Control. The designer finally found them only last year when we were both showing work in Bristol as part of the Vanguard show about graffiti in Bristol alongside some other contemporary street artists.

I have a fantastic new designer on board and I think one of perhaps the top three photobook printers in the world.

The Kickstarter has some fantastic new music rewards to go with the book. We have digital downloads donated by some music icons from the time. Deep house and disco diva Grace Sands has donated an hour-long mix of unreleased tunes. She was originally part of the legendary DiY Soundsystem. Desert Storm have donated a mix dedicated to the memory of their main man Keith DS23 who took their rig to Bosnia during the civil war there. The awesome Ixy from Spiral Tribe has donated a 30th Anniversary of Castlemorton mix to go with the book and Steve Littlemen from Smokescreen Soundsystem has given us his Forward Motion mix specially created for Exist To Resist.

Read this next: Nocturnal & neon: Photographer Greg Girard spent 30 years immortalizing Asia at night

To create some contextual history for the project we also have the original rewards for download once again that include the Operation Solstice documentary about the Battle of the Beanfield. Sunnyside soundsystem’s Jen Jen will be represented by Break It, a mix recorded live on DAT at a 1995 free party in a field. We also have the incredible and unique 10 track download made up of tunes from the Liberators, Laurie Immersion, Gizelle, DIY and other legends like Sunnyside’s Rowland The Bastard. DAVE The Drummer mastered it for us and Sunnyside’s Dj Needlefluff made the perfect mix.

We have been getting some incredible support in these hardest of times and are now nearing 50% funded but there is still a way to go. It’s a unique book that did incredible things last time around. Exist To Resist v2.0 can’t happen without you.

Back Exist To Resist v2.0 on Kickstarter here

Patrick Hinton is Mixmag's Editor & Digital Director, follow him on Twitter