Interviews

Interviews

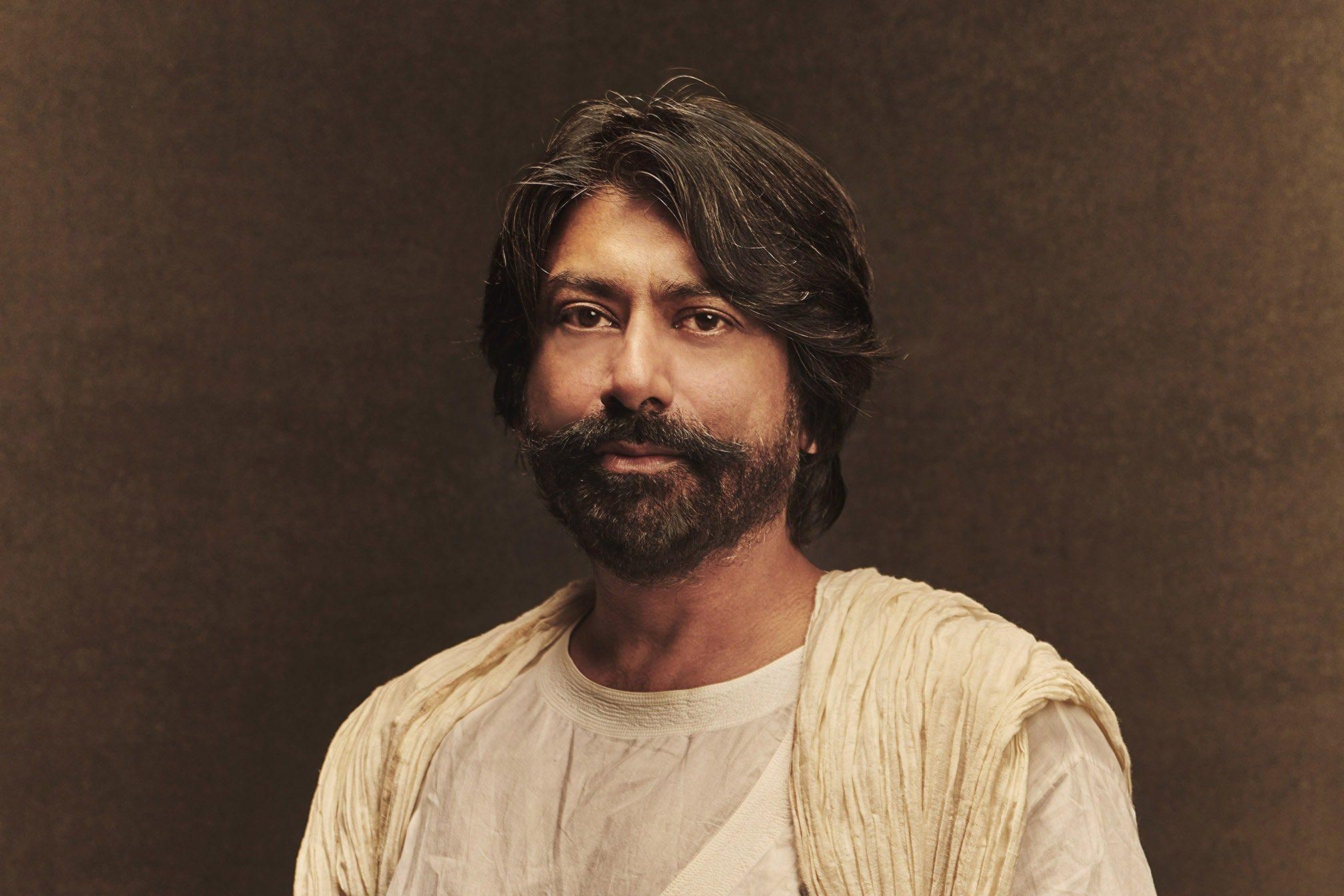

Talvin Singh: “I wanted to break rules. It was a beautiful experience”

Safi Bugel speaks to Talvin Singh about his revolutionary career in music, the new Asian Underground, and why he's "very, very surprised" about his first solo record in 15 years

Since the recent drive for representation of British Asian DJs, and the inception of events like Hungama and Dialled In, it’s no longer rare to hear a South Asian vocal, instrument or melody blasted on a sweaty dancefloor at 3:AM. But when Talvin Singh co-founded Anokha in London two decades earlier, it was a revolutionary thing to find these sounds in a club setting. With its exciting open music policy, which spanned ambient and Indian classical to hard-hitting jungle, the night helped to push the boundaries of dance music and going out in the UK. The success of Anokha led to the release of a compilation of the same name and subsequently ushered in the birth of the Asian Underground, a generation of British Asians who championed a blend of electronic music with different genres from the Indian subcontinent on a major scale.

But Singh has also celebrated many milestones as a musician in his own right. After training in tabla as a child, he went on to collaborate with industry stars including Björk, Madonna and Sun Ra on stage and in the studio; in 1998, he released a Mercury-winning debut album which connected different styles, scenes and subcultures with its pairing of traditional Indian forms with razor-sharp drum 'n' bass. His wide-reaching catalogue of musical achievements — from producing film scores and remixes to training young artists and playing shows across the world — landed him an OBE in 2015.

Read this next: Exploring identity: What does it mean to be a South Asian in the UK in 2021?

When I speak to him one day in August, he’s in the middle of a studio session in Mumbai. Now in his fifties, the composer, producer and percussionist is tying up the final threads of his first major release in over 20 years, which harks back to his ‘90s drum ‘n bass roots.

He’s also looking forward to his fully improvisational Southbank Centre performance in collaboration with Coby Sey and Lucinda Chua as part of Nicholas Daley’s Woven Rhythms series. In the lead up to the show, we talk about the foundations of his experimental approach, collaborating with some of the best in the industry and the evergreen appeal of British Asian music.

You came of age in Leytonstone across the '80s and '90s, what kind of music were you listening to at the time?

From the very beginning, there was a constant closeness to Indian classical music, whether it was learning, playing, listening or watching. But I was also very close to jazz and electronic music – early electro and then house. When jungle first happened, I was like: wow, we’ve arrived. I kind of felt so many things had just landed together, that melting pot of sounds. It was like a cohesive playground of all these different musical styles: I could even feel elements of Indian classical music in it because of the importance of drones. That wasn’t necessarily in there, but I could imagine it.

When did you start connecting the dots between these different styles in your own music?

My early recording experiments at home, around 11 or 12 years old, were playing tabla to electro beats and then re-recording them from tape to tape. I had been playing tabla since the age of five and I knew I needed to practise with a metronome, but I found a metronome really boring. I started practising with electro beats as a metronome instead, and it just kind of went from there.

Read this next: Yung Singh announces debut Asia Tour

What about beyond the home? Can you describe the music and clubs scene in London?

I was too young to go out clubbing but, you know, we had access to the street. The breakdancing thing was happening and it allowed a whole diversity of people – no matter where you're from, where you live, how old you are – to get together to play music and dance. I think that was a very special time: the clubs were on the streets then.

As soon as we did start clubbing, there were a lot of raves happening around East London, especially around the Stratford area. There were all these squatting parties and there was just amazing music that was free access. There was no element of segregation, especially in dance music. Venues and clubs were the only place that there was no racism. I think there was probably more racism in offices, in professional sectors and other industries. When it came to music, everyone was just together.

Were there any stand out nights?

Definitely. In Covent Garden, there was a small club that played really good house music on Wednesdays - it was called Gardening Club, and it had great, great sound in there, a really good system and very intimate. Everyone who played there was on it: Darren Emerson, early Chemical Brothers, Andy Weatherall. And then the bigger spaces happened. Places like Heaven were amazing. There were three rooms there: a really large room which was quite ravey, a smaller room which was more intimate house, and then there was always this ambient room, where you just listened to so many amazing soundscapes. They were really good times there.

In 1995 you set up Anokha with Sweety Kapoor, can you give me a sense of the club night?

Every Monday night, downstairs was just full on pressure, pretty much 160-170 BPM, and then upstairs was a very exciting space that was more ambient soundscapes, trip hop beats, glitchy vibes, Indian classical. A lot of people stayed upstairs because they just wanted to listen. They wanted their spirit to dance, but not necessarily to physically dance. Once a month we would have a live feature; Squarepusher came and played a few times, as well as Black Star Liner who were also making great records at that time.

The club was happening before the record ['Anokha – Soundz of the Asian Underground', 1977] came out but when the record came out, it just went nuts.

How did it compare to other nights at the time? Did it change the clubbing landscape?

Definitely. It just brought a lot of colour, it was just very, very colourful. It wasn't just this segregated bunch of Asians listening to their own music of heritage, it was about South Asians being in a playground and expressing what they're doing, but yet it wasn't just them. It was just music lovers. There weren't that many Asians, it was definitely below 30%. It wasn't about being Asian, it was just a sound. It was a very exciting time.

Your debut solo album 'OK' (1998) built on your early pairing of Indian classical forms with electronic music, how did it feel to work on those ideas on a bigger scale?

I had collected so many musical ideas for so many years to make my own solo record as a composer and producer, so when I was given that opportunity with 'OK', it was just amazing. I wanted to create a travelogue where music starts sitting in a very universal way. I love the idea of connectivity between cultural genres, like why does this African beat sound so similar to this Indian beat? And then those ideas come together. That was the driving force. Also, my sonic perception of things which I'd learnt from Indian film music: how you can make big drums sound really small, and small drums sound massive. Even if you take tabla as an instrument, it's actually quite a soft, light instrument. It’s got a lot of dynamics, depth and melodic gestures but it doesn't have huge amounts of volume. When you're in the studio, you can really play with the perception, the volume is in your hand. So for me, when I did 'OK', I really worked with that, and how I can break the rules of these ethnographical ideas people – including the BBC! – have. I wanted to break those rules. It was a beautiful experience. The process of making the record was for me as exciting as the actual product itself.

Read this next: DJ Nobu, Acid Pauli, Nicola Cruz & new Wonderfruit 'residents' added to 2023 line-up

The record was extremely well received, winning the 1999 Mercury Prize – did you ever expect those sounds, or that breaking down of rules, to reach the mainstream?

As tabla players, there's been a few of us on a slight mission to bring the instrument further to the forefront. I think tabla, even in the Indian context, was more of an accompanying instrument, to accompany vocals or instrumentalists rather than solo (even though there is a traditional solo repertoire). But I think bringing it forward on the stage, and a central stage, has been a mission accomplished by some key tabla players. I suppose I've had a small role in that in my own way too.

With the album, I think I was quite lucky. Lucky to have not had people sitting on my head, like record companies looking for a record that they're expecting. I was given a complete open playground to make the record I wanted. I suppose a lot of people were quite surprised, but I just made what I needed to make, I didn't make it for any other reason.

Throughout your career as a producer, composer and percussionist, you've also collaborated with musicians like David Sylvian, Ryuichi Sakamoto and Siouxsie Sioux. Next month you’ll perform live with Cobey Sey and Lucinda Chua. What is it about collaboration you like or value?

As a percussionist, collaborating and providing rhythm to a melodic gesture is something which is part of what I do. I learn so much from these collaborations and I enjoy any opportunity to make music with someone who's sonic vision and sound I respect, like Coby and Lucinda – brilliant, brilliant musicians. We're so excited to come together. We're not going to rehearse, it's going to be completely improvised, so that way it's something which can never ever be repeated, and that's something that makes it even more valuable.

Is there anyone you particularly enjoyed working with?

I learnt so much from Ryuichi Sakamoto. He was always a guide and a mentor for me. The first time I was doing a full-on film score, I called him for advice and he gave me brilliant advice. He was always there. I feel very lucky and blessed, we do deeply miss him.

Despite working on projects that span everything from Indian classical to drum 'n' bass, pop and new wave, you've said in interviews that you don't like – and resist – the concept of 'fusion music'. Why is that?

It's over simplistic. It’s also disrespectful to call anything other than jazz fusion “fusion”. That's how I see “fusion music”, I never ever see what I'm doing as fusion. Because I mean, everything's fusion and nothing's fusion, right? Tabla in itself is a fusion of one drum and another drum, and a fusion of many Indian percussion instruments.

I like shades, I like bringing the darkness and light together. You sometimes hear a lot of darkness and pain in my music. I think that also comes from partition, it comes from our ancestral pain, about things that are whitewashed and Brown-washed history that we never get to know. There's always sections of pain, even if it's a dance track. You're always going to hear some discordance.

So you see your music as less of a ‘fusion of East and West’, but something more nuanced?

Oh yeah. My focus is definitely how tabla can be explored into new territories, without too much of a compromise on the architecture and the language of the instrument. How can you bring it up to a contemporary space? People like Nils Frahm do that really well: they're classically trained but their outlook is contemporary.

There seems to be much more genre-bending in music now. What do you think of the contemporary club scene, and the direction that dance music has taken since the 90s?

Genre was more apparent in the filing of records, CDs, in stores. Digital distribution has its pros and cons but one thing it has helped in is breaking done the rigid genre boxes. Sometimes the best music is made by breaking down the borders in genre.

Regarding the current club scene, it’s always interesting how things get revisited. At the moment, my nephew is going out raving and listening to really traditional drum 'n' bass! I didn't experience that in the '90s because everything was fresh and new to me, but now I've realised: oh ok, there's a comeback of that, of this. It's always very exciting how it just goes full circle.

Read this next: Artist Spotlight: Audio-visual artist Sijya draws introspection from candidly living in the present

Is it strange to see the renewed attention to the sounds of the Asian Underground 30 odd years later, through events like Dialled In and groups like Daytimers?

I think it's great. I always knew it was gonna happen, that it would always reignite itself, because there's history there. What I love is there's so many South Asian, Sri Lankan, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Indian origin DJs. There’s also more female DJs making brilliant music than there are men, I think it's great. That feels so good. Daytimers and Dialled In have done so much brilliant work. We have a lot of love and respect amongst us: they give me a lot of love and respect and I return that to them. I'm really happy to bring out my record at a time like this.

It’s been 15 years since your last solo record. How does your upcoming one compare to your previous ones?

There's some beautiful songs, with some really good vocalists. I pretty much play most of the instruments myself; there's a couple of classical flute and sarangi which I've recorded on a few tracks, a few instrumentals. I'm very, very surprised because I've also gone back to drum ‘n bass. I didn’t want to be boxed into that, so I didn't want to make that kind of sound any more, but I’ve gone back there. There's some tech-house tracks as well, on that kind of vibe. I'm quite surprised with this record. It is a journey: it's a kind of cohesive journey of music which I hear in my head and ideas which just touch my heart. I kind of only make records for myself to be honest, for me to listen to and enjoy!

Get tickets for Talvin Singh x Lucinda Chua x Coby Sey at the Southbank Centre here

Safi Bugel is a freelance writer, follow her on Twitter