Inside Glastonbury’s South Asian-focused Azaadi Stage in full colour

Making its debut drenched in marigolds, we chat with curator Bobby Friction about the festival’s latest addition that delivered a vibrant, rhythmic celebration of culture & innovation

What’s left to say about Glastonbury that hasn’t already been said? Arguably the mecca of music worldwide, few festivals match its scale and ability to spotlight creatives from all walks of life.

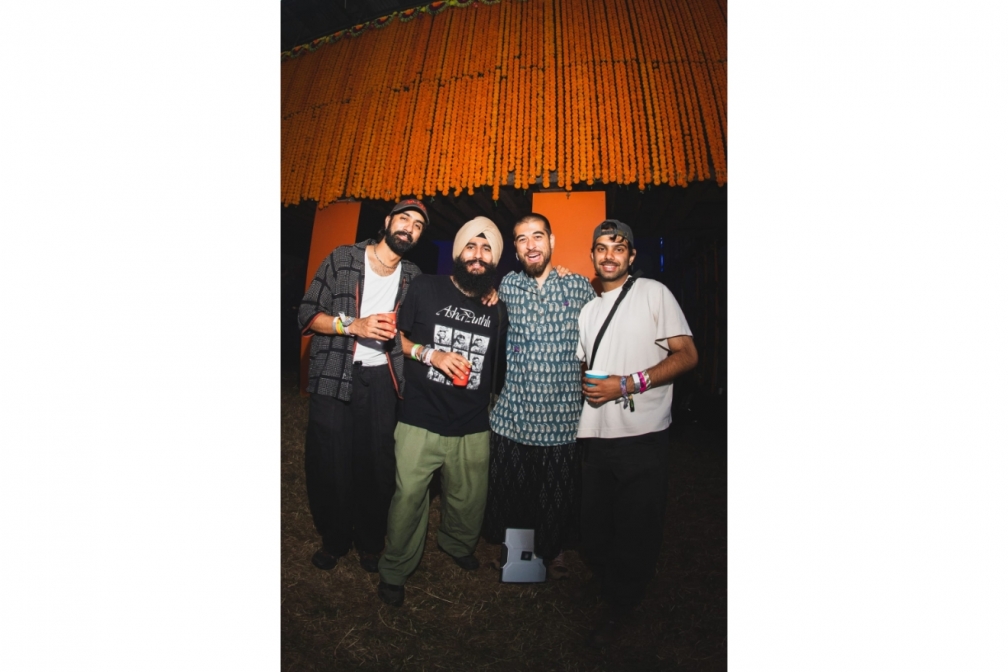

Tucked inside the infamous Shangri-La, one stage that turned heads this year, was the Azaadi Stage.

Curated by Bobby Friction—the influential British-Asian DJ, broadcaster, and cultural advocate who served as Azaadi’s Executive and Creative Director—the stage was a full-bodied celebration of South Asian sound. From line-up to crew, everything pulsed with the spirit, vibrancy, and innovation of the region. How many stages are laden head-to-toe with marigolds?

Before diving into the wildly exciting gallery capturing the chaos, joy, and love that radiated from this special space, read Henry’s chat with Bobby and what he had to say about Azaadi’s debut at Glasto, the importance of South Asian representation, and why the global rise of its sounds is only just beginning.

Firstly, tell us—how was your Glastonbury this year?

The hardest I’ve ever worked. The most ambitious in scope. The most hours put in, the most tears shed, and the most sweat...But ultimately, for you, glorious. Because we saw so many thousands of people not only have an amazing time with something weird we conceptualised, but actually realising they felt that Azaadi was their home at Glastonbury. How many hours were we whining? A bit too many...

It was the first Glasto since 1992 where I stayed in one spot for the entire, nearly two weeks I was there. And during the festival, I didn’t leave the Shangri-La area at all. Most of the time, I was stuck—almost chained—artistically and existentially, to the Azaadi stage.

How was the response to the stage and the artists?

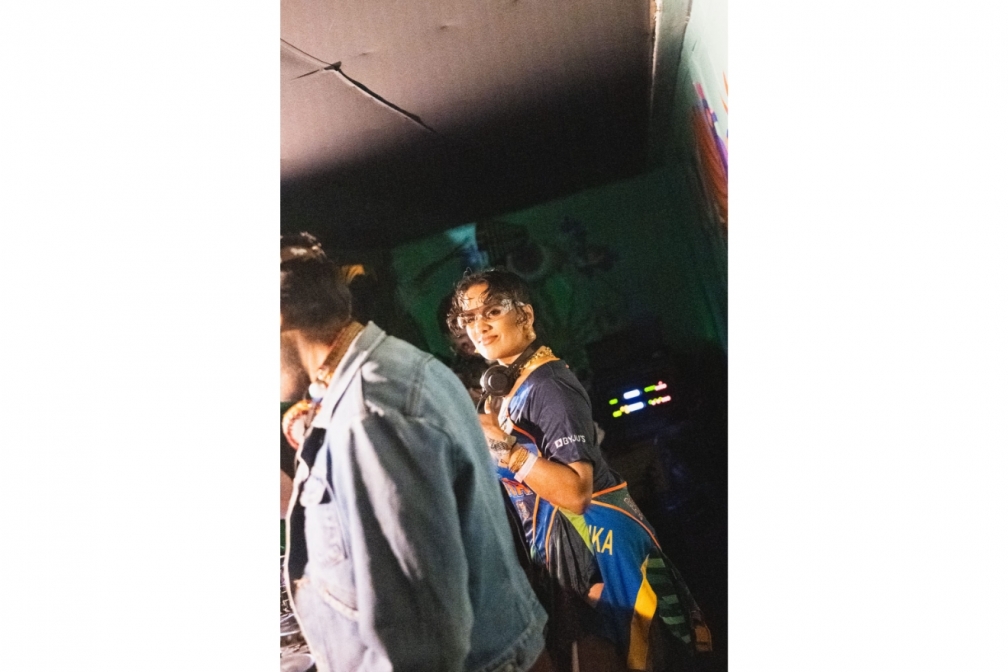

For us, the response to the stage and artists was everything we dreamt of and more. The whole point wasn’t to say, “Oh, there’s South Asian music and artists here”. The point was smashing ceilings, breaking down artificial divides, and letting everyone access so many South Asian artists; some of the best music being made in the world.

The response was amazing. Seeing so many people love it, not even knowing it’s a South Asian stage or South Asian sounds, and just loving it was amazing. The demographic cross-section of people there... it was a place to be enjoyed by everyone. And that’s exactly what we wanted.

We wanted to invade the current global music space with radical joy and happiness.

What kinds of conversations were happening during the line-up curation?

So I did the line-up curation by myself. The conversations during line-up curation... I curated it how I curate my radio shows, which is a different way.

When you think of live music and desi vibes, you think about the time (night or day) or what a Friday night means. Whereas I think, “Oh, I’ve got someone listening to my radio show; how can I keep them locked in for the full show?”

Everyone has their own way of doing it. I want to keep the texture multifaceted. If someone’s only there for 15 minutes, they hear three completely different-sounding tracks that meld into each other. That’s how I did the initial curation.

Then I looked at it and thought “this is real”. These are real days and real timings. People coming on at 10pm or 3am. I then did what most curators do and put in a bit of reality. But my foundation was a radio foundation.

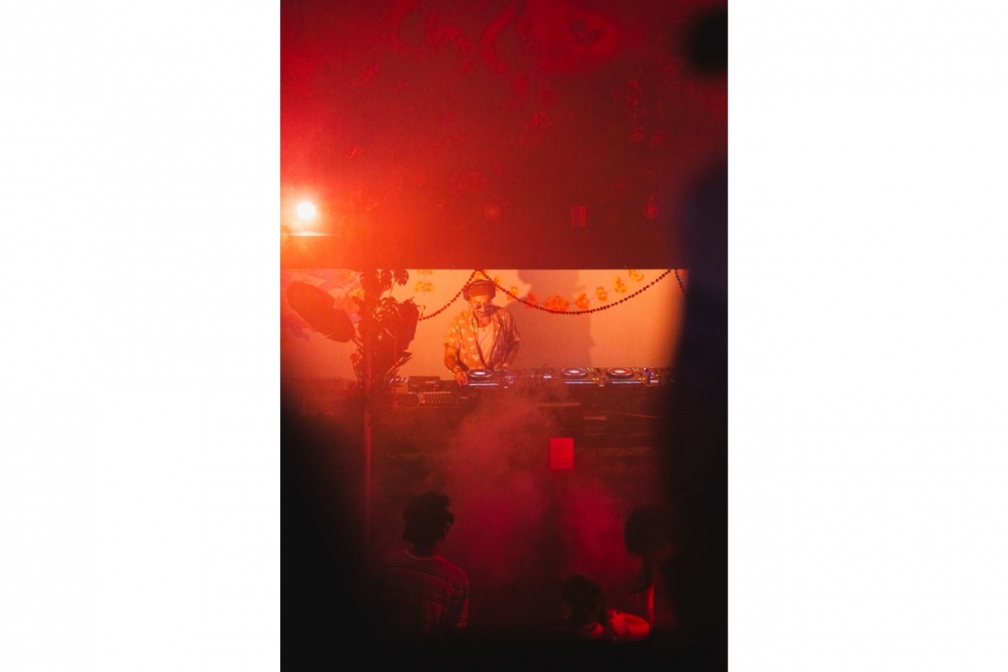

Did some night and day stuff. On top of that, I knew there are certain acts that only work on a Friday or a Thursday and that’s more tonal. For example, Sukh Knight could’ve worked anytime on a Thursday, or finishing the night on a Friday. But Glasto has a tradition of Sunday being very dub reggae. Him being the closest thing, with his unreal South Asian grimey dubstep sounds, worked perfectly.

Without wanting to be a box-ticker, I did want to have a good gender mix and region mix. I didn’t want it to be all Pakistani or all Indian. We wanted a diverse South Asian sonic imprint.

One convo I had with myself was, “What’s that big moment?” That ended up being us booking Bally Sagoo. He hasn’t played in the UK in decades. He’s seen as the godfather of South Asian remixes. He started with that old generation, but what he did was really unique. He was producing with Bollywood and beyond, remixing in a very early ‘90s way—not actually remixing on a laptop, but reproducing the track. He’s a pivotal figure in South Asian music.

We booked him, he played, and it was fucking incredible. Nearly every South Asian DJ was in Azaadi for his set. Him being in the industry for 40 years, you’d expect him to just play his classics, right? No. He had four decks and played like the best current DJ. A proper badman. He remixed and refixed every single tune just for Glastonbury. It was a special, special thing.

If someone wandered into Azaadi with no context, what do you hope they leave feeling or thinking?

On a surface level, I’d hope they’d leave with the visual iconography of the place. A lot of thought went into that from our great team. I’d hope it would hit someone, and they’d pick up on the beautiful, South Asian-centric and green, mother-earth-centric iconography. We wanted to do “The Wilding” (the Shangri-La theme) with a South Asian spin. Still in Shangri-La, but really take that South Asian flex up and away.

Sonically, one thing that’s powerful about South Asian electronic music is that it’s very big on the beats. Very percussive culture. We’re also a very melodic culture musically. There’s a whole layer of melodicness across various subcultures. I’d really hope that without any context, people would be moving to the beat…but their heads would be in sublime submission to the melody. Because that’s what happens to me!

How did this year's Glasto theme, “The Wilding”, shape Azaadi’s design, vibe, or message?

My entire team were chatting with Kaye Dunnings, who runs Shangri-La. It was clear; it’s not just “The Wilding” as in trees and stuff. It was about a return to analogue life. A rejection of digital life. We built Azaadi around that. One of the reasons we named the stage Azaadi is because it means “freedom”, and essentially, The Wilding was about freedom. Freedom from the digital world. Freedom that mother earth represents. That was all wound into Azaadi’s design and message, lovingly produced by Going South and Lila Music.

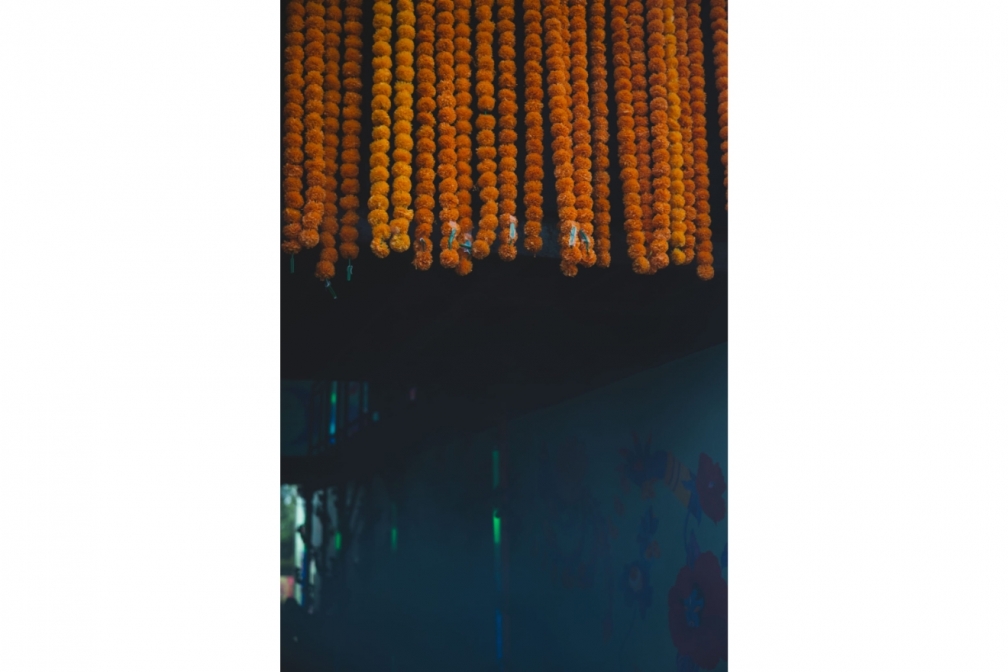

Credit to Kushiana, the visual artist who designed the poster—all the inside décor was derived from that poster. It became a forest. Then a jungle. We also had Sophie Anwar, one of the stage designers alongside Junsei Daniel. Someone mentioned the word “flowers”, and I just went “marigolds”. I love them. They’re symbolic in South Asian culture. We pictured a venue covered in them.

As we picked up amazing people to work with along the way, everything changed. But when the gates opened, the initial conversation of a stage covered in marigolds still happened.

Azaadi is described as a training ground for South Asian creatives. Can you tell us more about the behind-the-scenes infrastructure you built?

The infrastructure; a training ground for South Asian individuals. We feel this is especially important. You know, when I was coming through, say 20, 25 years ago, there weren’t many South Asian creatives behind the scenes. Yes, there were when we did our own gigs, but in big, established places, there was a glass ceiling. And it wasn’t even like, “Oh, it’s so racist…Sometimes it was our own culture, our own parents holding us back a bit.

What we tried this year, following on from last year’s collab with Dialled In and Daytimers, was to have as many people working on it being South Asian. Not as a rule, but just taking each role individually and asking: who can we give a leg up to? We wanted people to mentor, and people to mentor us. Lots of young people wanted to break into the industry, and we were so happy to help support these amazing people.

Without the family we built (we had people who had never been to a festival, and people that had been to festivals non-stop!), everyone had to get involved and teach each other. There was a lot of exchange of skill sets. But the whole point was to make sure it was positive. Something where we’re “watering the seeds of the plants” (Not to sound cheesy!). We just kept watering each and every seed to ensure the beauty of South Asian culture could bloom.

In your own words, how would you describe the “South Asian sound”?

There’s no such thing as the South Asian sound. But there is a South Asian vibration.

The sound changes—from classic to now, from electronic to Bhangra. The way I describe it is: there’s something about all South Asian music that is bass-heavy and percussive-heavy, all representing different areas of sonic space.

But we’re so heavy on the other end too; the melodic end of music, just as much as we are on the percussive side. If we whittle it down, it’s a meld of the two worlds. The percussion is dominant and complex…and the same happens with the melody.

The South Asian sound is about dominant and complex beats and melodies on top. It’s easy to say, “Oh that sounds Bollywood,” but overall, it’s the whole package: complexity mixed in with simplicity, and vibrations all at the same time.

What does it mean to reframe South Asian culture not through nostalgia, but through futurism and radical imagination?

Oh, I love this question. It’s so important.

This is just me, but when I’m not thinking about music, I’m thinking about space and planets and telescopes and bio-organisms. I’m always going to be involved in stuff that feels futuristic.

That’s always been there. But it’s working so well now because we’re living in hyper-technological times. Most of us understand the current situation with AI and tech.

People used to say, “It’s the second industrial revolution.” Now, people understand it’s more than that. It’s like the invention of fire, the printing press, and the industrial revolution all at once.

I think it’s important to look forward, not back. We look back to stay grounded—to know where we came from so we can know where we’re going. But artists who are ahead of the rest of us need to explain this technological creation — this mad cauldron of fire and genetics we’re living through now—through art. Most creatives are thinking around futurism.

Secondly, we do run away from our past. I know a lot of North Indian, Bengali, and Pakistani people—we still carry memories of the genocides of 1947 and 1971, and even more. I’m only one generation removed. My fucking dad went through that.

So when I look forward and see love, I don’t want to look back. I want to see a future where all this South Asian connection is built through love, not through trauma. That’s why futurism works so well.

Why do you think the global appetite for South Asian sound is growing now?

One is fortuitous timing. The other is people needing something new.

The global appetite is growing because there’s now so much more diversity. People in the UK used to not even know about Sikhs, Pakistanis, Indians, etc. Whereas now, there’s such a diverse diaspora around the world. We want to understand ourselves. We want to take some of the magic and light from our culture and mix it up around the place. That’s being British to me. I’m so proud of this country and my part in this country.

The diaspora growing is definitely a big thing.

There’s also people in the West looking for what’s next. Innovation is necessary now. So many guitar riffs have happened. Rock, hip hop…every style of rap has been done. It’s hitting the same brick wall rock hit. That opens up space for radical reinterpretation. Even if you knew every 808 and snare in electronic music, you’ve heard it all. But now it all mashes and clashes with South Asian sounds, and it’s like a huge new radical path to go down. Another rabbit hole to get sucked into.

Our Western brothers and sisters don’t even need to think, “Oh, I want to hear South Asia.” It’s just about mixing in with the diasporas and creating new stuff for everyone to enjoy. That’s why I think its time is now.

Finally; if Azaadi could leave behind a single ripple effect in the UK music landscape, what would you want that to be?

If Azaadi could leave behind one single ripple in the UK landscape... I’d want it to be that everyone who knows about it, understands that it’s a joyous, colourful, fun, innovative space that represents the future. I want it to feel like black-and-white turned into colour TV. I want our stage to do that to everyone who walks through it.

I want people to think, “Remember when I went to Azaadi that one time? Look at it now.” And then have it evolve and grow and move into new spaces and subcultures. That’s the main ripple I want it to have.

[Images via Yushy]

Henry Cooper is a Writer at Mixmag Asia. Follow him on Instagram.

Cut through the noise—sign up for our weekly Scene Report or follow us on Instagram to get the latest from Asia and the Asian diaspora!