Features

Features

Voguing: A brief history of the ballroom

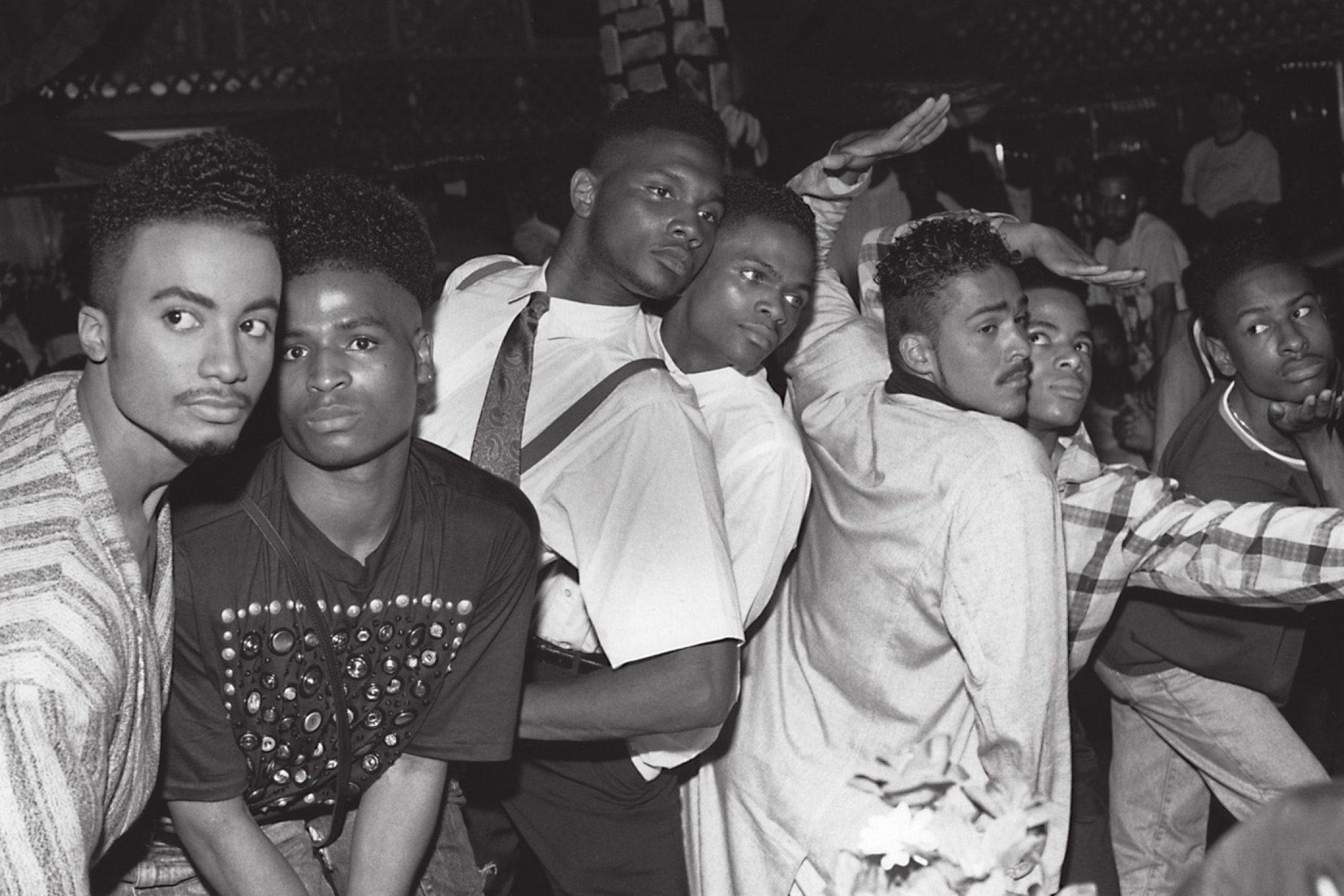

Life’s a ball — here's Mixmag's potted history of voguing

Almost three decades after it strutted, high-kicking, out of the Harlem drag balls into mainstream culture in the summer of 1990 – thanks mainly to Madonna’s ‘Vogue’ and the documentary Paris Is Burning – vogue, the dance and the culture, continues to be as culturally relevant as ever.

As well as continuing to provide a platform for MCs, DJs, dancers and designers, the ballroom scene still infiltrates mainstream culture in typically fabulous fashion. It’s in the meticulously choreographed synchronicity of Christine And The Queens and FKA Twigs; Kanye protégé Teyana Taylor’s ‘Work That Pussy’ track and video are both serving 1990 realness; and international brands such as Nike and directors like Gaspar Noé are still drawing inspiration from the scene in 2018.

Though it rose to prominence in the mid-1980s, New York’s drag ball culture can be traced right back to the first Annual Odd Fellows Ball (later known as the Faggots Ball or Fairies Ball), held at Harlem’s Hamilton Lodge No.710 in 1867, where men and women gathered to dress in drag to compete as the most convincing impersonator of the opposite sex. The balls steadily gathered momentum throughout the jazz age and early 20th century, before rising racial tensions, both in ball culture and America as a whole, erupted in the 1960s when Crystal LaBeija accused organisers of racism and rigging the vote, costing her the first prize in the All-American Camp Beauty Contest. It prompted her to begin holding her own black ballroom events, where attendees were later welcomed into ‘houses’ and asked to compete in a variety of categories, including Butch Queen Realness, European Runway, Town & Country, Face and Executive.

Offering “a home to those that don’t have one”, each ‘house’ had a ‘Mother’ or a ‘Father’ who took on a mentoring role and looked after young, mostly black or Latino gay men, known as ‘children’, who had found themselves the victims of rejection by their biological families, as well as often suffering abuse, homelessness and addiction. The Mothers and Fathers of the houses became surrogates, often providing people with a home and a place where they belonged while they competed against the other houses, a host of which followed in quick succession – including the House of Xtravaganza, the House of Omni and the House of Ninja, among many others.

As many of the children’s lives had been marred by violence, rejection and hostility, the battle element was introduced as a non-violent way to achieve supremacy. As the sentiment and loyalty of the houses echoed gang culture of the 1940s and 1950s, the battles were part dance-off, part fashion face-off. Though the winner only received a trophy, the real prize was the sense of achievement and acceptance that came from it. As Dorian Corey, Mother of the House Of Corey, says in Paris Is Burning, “In Ballroom we can be whatever we want. It is our Oscars – our chance to be a superstar.”

As competition between the houses intensified, voguing emerged as the trademark dance style of the drag balls. “It all started at an after-hours club called Footsteps on 2nd Avenue and 14th Street,” says DJ David DePino, a legend of the scene thanks to his sets at clubs such as Paradise Garage and Tracks. “Paris Dupree was there, and a bunch of black queens were throwing shade at each other. Paris had a Vogue magazine in her bag, and while she was dancing she took it out, opened it up to a page where a model was posing and then stopped in that pose on the beat. Then she turned to the next page and stopped in the new pose, again on the beat. Then another queen came up and did another pose in front of Paris, and then Paris went in front of her and did another pose. This was all shade – they were all trying to make a prettier pose than each other – and it soon caught on at the balls. At first they called it posing and then, because it started from Vogue magazine, they called it voguing.”

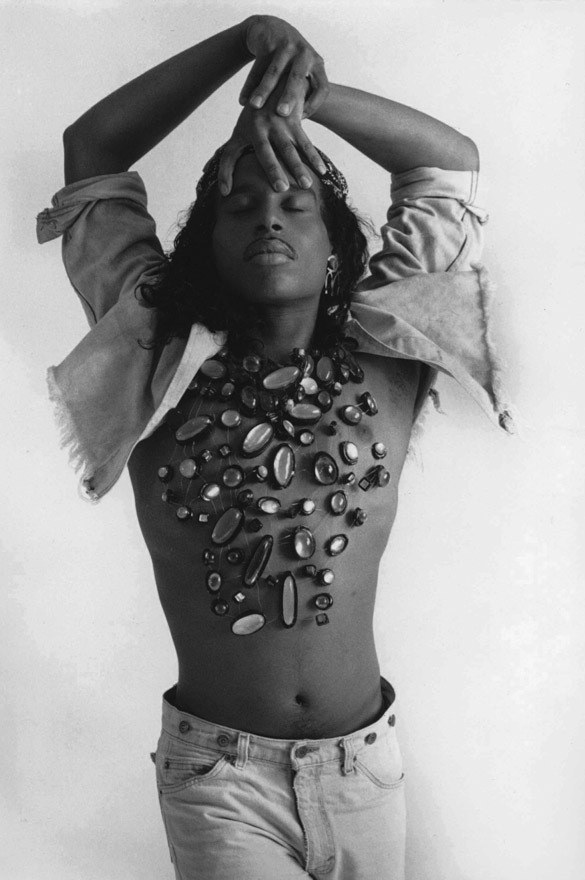

As new dancers brought their own ideas and identities into the scene, the dance evolved from Old Way (almost static, balletic poses transitioning from one to another) to New Way (based on the traditional voguing but incorporating more athleticism and martial arts-inspired moves, and best exemplified by Willi Ninja, pictured right) and, later Vogue Fem (ultra-feminine choreography with intricate posturing, hair whips and deathdrops), so too did the music. With attitude and arrogance key characteristics of voguing, the music evolved from classic disco and Philly soul to pounding house beats, sliced up with snatches of dialogue and film monologues.

Ball favourites included MFSB’s disco classic ‘Love Is The Message’, Shep Pettibone’s remix of Salsoul Orchestra’s ‘Ooh I Love It (Love Break)’, Junior Vasquez’ ‘X' (a homage to the House of Xtravaganza) and ‘Get Your Hands Off My Man’, as well as 1989’s ‘Just Like A Queen’, which Vasquez recorded under the pseudonym of Ellis D. The importance of the music was best outlined by online voguing source, the House of Diabolique: “These are more than just bitchy songs; they form a soundtrack of power, control, manipulation, escape and fantasy. They glorify gayness and femininity.”

As the voguing scene grew (in 1987 Time magazine proclaimed it ‘the new breakdancing’ after the Brooklyn piers were littered with pre-ball voguers rehearsing their moves), it spilled out from downtown discos and glammed-up function halls to major clubs, as the dancefloors of Tracks and Paradise Garage (Larry Levan was a member of the House of Wong) were transformed into honorary runways for the voguers to catwalk their way to receiving “10’s across the board” from the event’s judging panels and trophies designed by luminaries of the downtown art scene such as Kenny Scharf and Keith Haring.

Naturally, as the scene began to attract a starry following, voguing and ball culture began to receive attention from the mainstream media. Renowned face-about-town Chi Chi Valenti’s husband, Johnny Dynell, a DJ at Tunnel and member of House of Xtravaganza, sent Malcolm McLaren some early rushes of Jennie Livingstone’s Paris Is Burning documentary, hoping to secure financial backing to get the film released. McLaren gave the tape to Mark Moore, who he’d asked to work on some remixes; Mark – with permission – sampled snatches of dialogue for his and William Orbit’s version of McLaren’s ‘Deep In Vogue’ album track, which also featured raps from Willi Ninja and David Xtravaganza. McLaren re-released the track as a single and it became a big club hit, reaching No 1 on the US Billboard dance chart in July 1989. Valenti went on to successfully sue McLaren for plagiarising her on the track. It quoted some lines from her seminal voguing essay ‘Nations’, published in Details magazine in 1988.

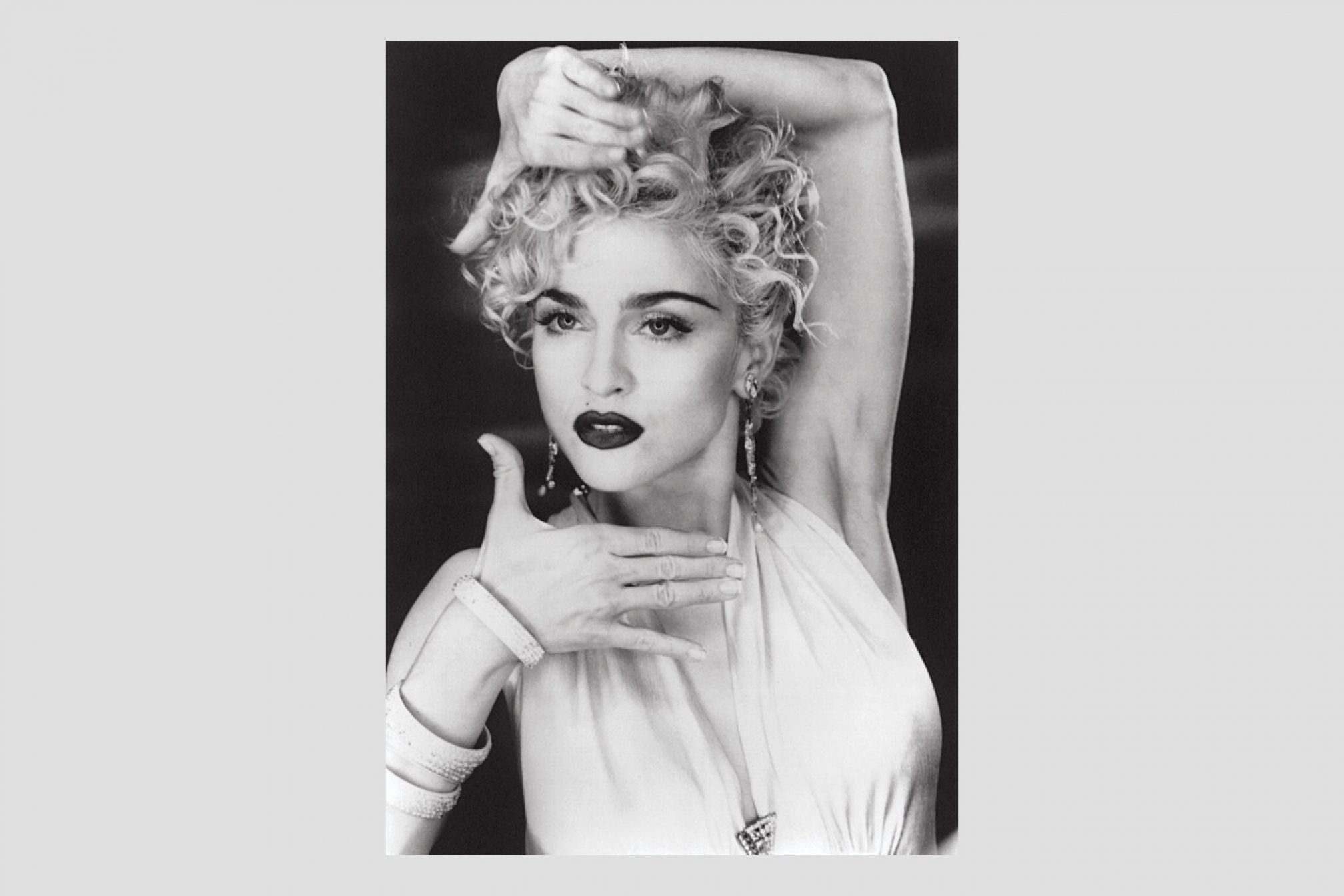

McLaren’s track – and its iconic video showcasing the talents of Willi Ninja – was key to voguing’s infiltration of mainstream culture. The fashion scene which had inspired the dance was first to adopt it, designers such as Thierry Mugler and Jean Paul Gaultier featuring voguers in their catwalk shows. But ball culture’s true coming out moment arrived on May 10, 1989 with The Love Ball, a glitterati-filled fundraising event which exposed ball culture to New York’s elite and powerful – including Madonna.

It was just weeks later, while voguing at the recently opened Sound Factory nightclub in New York alongside fellow House of Xtravaganza member Luis Camacho, that Jose Gutierez Xtravaganza met Madonna. “I was introduced to her by a mutual friend, Debi Mazar, at the Sound Factory,”

Jose recalls. “She was sitting on top of a speaker in a cap and trenchcoat, looking nothing like you’d expect Madonna to look, and Debi took me over to meet her. We talked for a while and then she asked me and Luis [Camacho] to vogue for her on the spot, so we did. She loved it and asked us to sit with her to advise her who else in the club was good. She said she was doing this video that she wanted us to be in and maybe a tour as well, so invited us to the auditions, where seven of us were chosen from five thousand. Then she asked us to choreograph the video and to teach her how to vogue…”

Released in March 1990, ‘Vogue’, Madonna’s ode to the scene she had fallen in love with, went on to top the charts in 30 countries and became the biggest-selling single of the year. Co-written and produced by Shep Pettibone, who reproduced the drum pattern and synth stabs of ‘Deep In Vogue’ and added an interpolation of ‘Love Is The Message’s bassline, ‘Vogue’ featured a lyric which encapsulated the essence of ballroom culture perfectly; “It makes no difference if you’re black or white/If you’re a boy or a girl/If the music’s pumping it will give you new life/You’re a superstar/Yes, that’s what you are, you know it”.

Although a global smash and voguing’s biggest breakthrough moment, Madonna was criticised by certain sections of the community for appropriating their culture for her own gain – something Jose dismisses. “She didn’t go to some Ivy League dance department and try to recreate voguing, she came to the club herself and sought us out,” he says. “What people seem to forget is the good that came from this great pop/gay icon taking voguing and putting it onto the world stage – giving it the platform it needed. She didn’t steal it, she came to the club and found two of the community’s own – myself and Luis – and took us with her. That was her way of honouring it, and giving it credit, and keeping it what voguing traditionally is.”

“SHE DIDN’T TRY TO RECREATE VOGUING; SHE CAME TO THE CLUB, FOUND TWO OF THE COMMUNITY’S OWN AND TOOK US WITH HER”

Director Jennie Livingstone found herself subject to similar criticism when her Paris Is Burning documentary was released the same year, with members of the ballroom community accusing her of exploiting them by reinforcing stereotypes by focusing on the tragic elements of the participants’ seemingly politically powerless lives, such as prostitution, AIDS and violence. An encyclopaedic excursion through ballroom culture between 1986 and 1989, Paris Is Burning contrasted the flamboyance and liberation of the balls with the tragedy and troubles that the participants were experiencing.

Though Livingston was criticised by some participants (a response to the film, How Do I Look? was released in 2006, purporting to tell their ‘real’ story), it would have been impossible to create an honest depiction of the scene without including the hardship experienced by those that lived it. The tragic story of Venus Xtravaganza, who was found strangled under a bed after being murdered by a john, was far from an isolated incident, while the spectre of AIDS loomed large and ravaged the community. Writing for The New York Times, Jesse Green lamented the untimely passing of so many ballroom legends: “Paris is no longer burning – it has burnt.”

Post-Madonna, and post-Paris Is Burning, the scene returned to being an underground subculture, rebuilding itself virtually from scratch. As the stories and experiences of the original Houses and their iconic performers were recounted via documentaries, books and belated memorial services, a new generation took the baton and, while continuing the legacy of those that had gone before them, used the progress that had been made in LGBTQI rights to continue to fight.

The Kiki scene, a youth-led component of the ballroom scene,has a political bias and fighter mentality fuelled by the injustices suffered by their predecessors. While many suffered the same problems as those of a generation earlier – rejection, addiction and violence – overcoming adversity was a case of when, rather than if. Taking place at balls such as Vogue Knights, House of Vogue and House of Yes, the kiki scene attracts an eclectic mix of styles – elegant transwomen, butch queens, rough banjee boys and a dazzling myriad of variants in between. The emergence of new categories has inspired the evolution of vogue performance and helped boost its crossover potential, with elements of breakdancing and gymnastics infiltrating the traditional style of dance and a more aggressive sound, fuelled by MCs spitting with freestyling ferocity over pounding tracks.

With Vjuan Allure and Mike Q creating unapologetically in-your-face ballroom anthems with names such as 10,000 Screaming Faggots and Kunt Darling, the reclamation and use of the insults hurled at them for decades was an exercise of strength and power. The vibrancy and the message of the scene was explored in the 2016 documentary Kiki, a collaboration between director Sara Jordeno and House of Pucci’s Twiggy Pucci Garçon. Described by Jordeno as a celebration of “an artform of defiance and resilience”, its message is optimistic and aspirational – an antidote to the air of impending doom that permeated Paris Is Burning.

Since the release of Kiki, the ballroom scene has increased its mainstream visibility to its highest point since its early-90s zenith thanks to its inclusion into campaigns by Apple and Nike (the #BeTrue campaign included voguing as a sport alongside basketball and athletics), performances from acts such as Beyoncé, FKA Twigs, Christine And The Queens, Mykki Blanco and Teyana Taylor, and TV series such as RuPaul’s Drag Race, Viceland’s My House (a docu-series following the lives of five vogue dancers and MCs), Gaspar Noé’s upcoming dance crew-focused movie Climax, and glossy, primetime TV drama Pose.

The brainchild of The Assassination of Gianni Versace and American Horror Story creator Ryan Murphy, Pose is a set in the 1987 ball scene, breaking boundaries with its cast of transgender leads and supporting cast of hundreds of LGBT extras. For all its show-stopping set pieces revelling in the bitchy battles, Pose is unflinching in its depiction of the dark side of the scene: two of the lead characters are HIV positive, while one mourns the death of his lover from AIDS, others sell themselves to pay for hormones or botched surgical procedures.

“I think it’s an important show because people have forgotten how bad it was back then,” says Jose, who plays a ballroom judge. “Those scary images of people literally deteriorating before our eyes have gone; people think they can just take a pill if they have HIV and still have sexual intercourse and yes, that’s partly true, and we have made great advances, but we also, with the internet and social media, live in a fake world, with people only posting what they want us to see – so I think it’s important to show how bad things were for the generation of twenty or twenty-five years ago.”

No longer exclusive to America’s urban black and Latino gay communities, social media and the internet age have allowed the ballroom scene to thrive globally – particularly in politically oppressed areas such as Russia and the Middle East, where it provides a vital form of self-expression for subcultures frightened and frustrated at not being able to be themselves, thus echoing the scene’s late-80s cultural positioning. Who says ‘there’s nothing to it’?

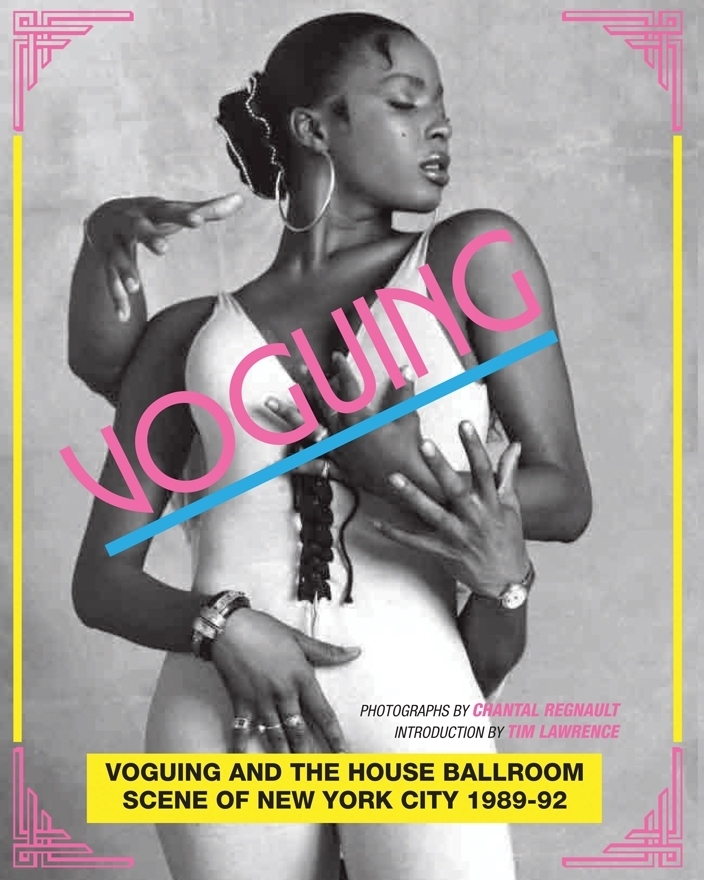

To see more of Chantal Regnault’s photos look out for the book Voguing And The House Ballroom Scene of New York City 1989–92 by Stuart Baker (currently being reprinted). Photos used with kind permission.