The Other Half

The Other Half

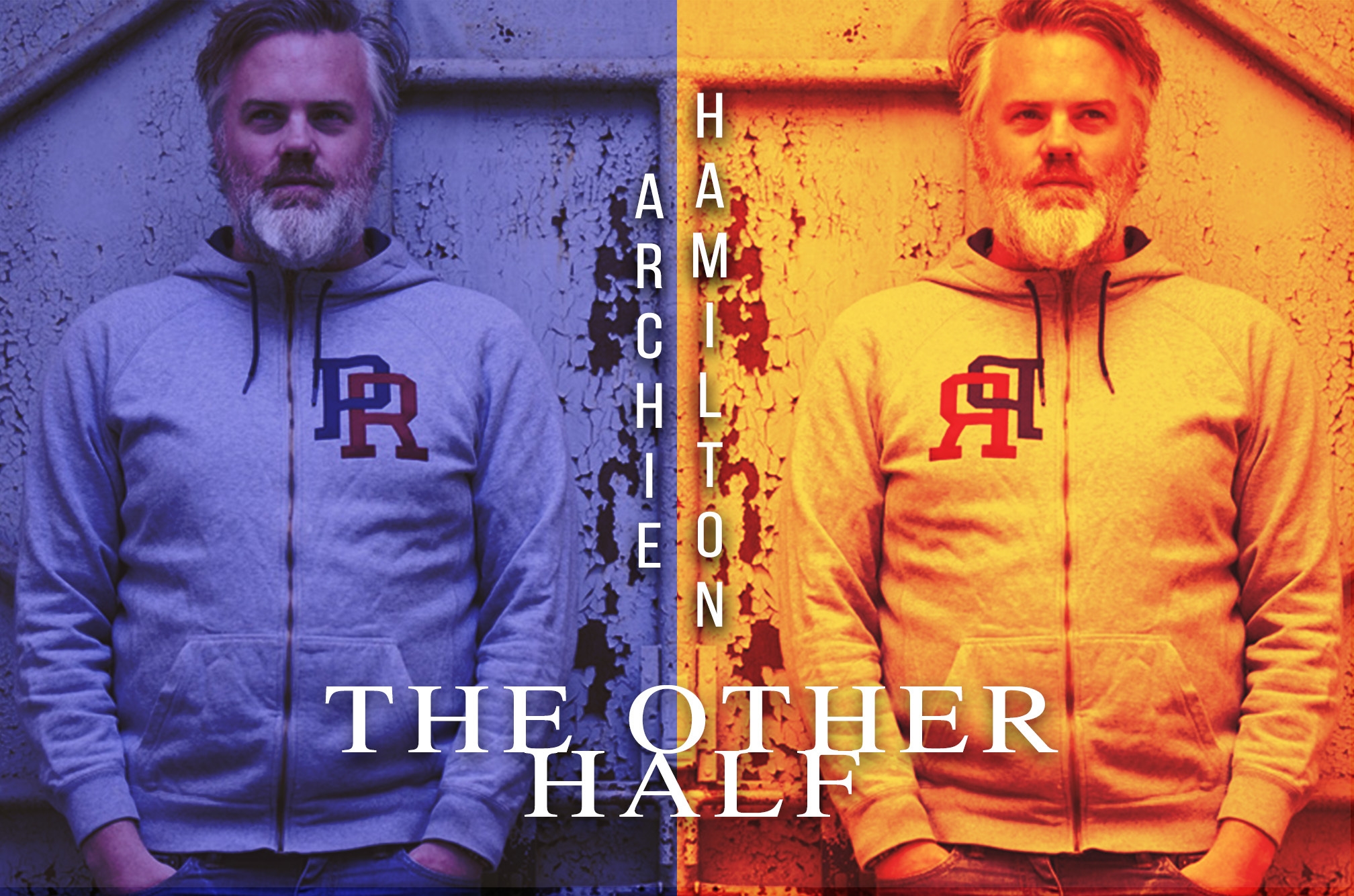

The Other Half: Archie Hamilton on making (and losing) money in China’s volatile music market

Wise words from someone who's lived it, lost it and learned from it himself

Behind every great dance artist, music festival, club or dance label, there is a business partner: otherwise known as The Other Half. Every month, we talk with these power players of the Asian dance music world — those that are behind the scenes, yet hugely influential. Through exclusive interviews, we’ll look at the hot topics of the moment, speaking with “those who know”.

Last month, we looked at the opportunities and challenges in the festival promotion business in Southeast Asia with Iqbal Ameer of Livescape. Today, we continue with the theme with a focus on mainland China.

We spoke with Archie Hamilton, CEO of Split Works, the Shanghai and Beijing based festival creator and music promoter. Moving to China in 2005, Archie jumped into the mainland music festival scene in its early days of development, creating and promoting events including JUE Festival and Concrete & Grass. Archie has lived through the ups-and-downs of the business in the mainland and shares his experiences with Mixmag Asia.

Otto Clubman: Thanks for joining us. How did you get into the music business originally?

Archie Hamilton: I started in the music business in the UK at the age of 18, when I was at university. I was an aspiring DJ, and then a promoter at a local club. I did try a proper job in accounting to make my parents happy, but that only lasted for nine months. I really believed in myself and thought I could make it as a DJ.

I took a trip to the Alps one year and was checking out the clubs there. The music at the resorts was absolutely horrible. I saw an opportunity to bring good music to these clubs – proper DJs and musicians. The tourists had the money to pay for them, they just weren’t being presented with the opportunity.

It was going well, and this led to an opportunity with the ChamJam, a local extreme sports event in the region. I had grown up with festivals – Glastonbury and such – and saw the opportunity to bring music to this extreme sports event. Essentially, we put on a “festival in the mountains”, coupling sports with music. It was great.

So, it was going well. What happened?

Well, we went broke. Ironically, we got too big and started getting a lot of attention. The local council viewed us as “too British”, and made things difficult. We ended up losing a lot of money and shut down. It was really painful. So, I headed back to London, got another real job, but within six months, I was ready to get out again. I looked around the world, trying to figure out where the music industry was still in its early stages. India and China both seemed like they had a lot of potential and were in the early stages of development. So, I decided to give China a try.

Did you go to China specifically with the idea of launching a festival business, or did you see the opportunity once you arrived?

When I got there in 2005, all the big international consumer brands were rushing into China. They were being told: go to China! Find an audience! But, they needed to find a way to engage that audience. These brands had tens of millions of dollars, and wanted to develop the youth market – but there was nothing to spend the money on. There was nothing available on the street level. I had the experience of building a community with our festival in the Alps, so I knew a bit about this.

What were the first brands you worked with?

We approached Bacardi and essentially said, “Do you want to be a part of the birth of live music in China?” They agreed to a series of twelve shows that would finish with a large festival. Of course, I had no idea how to do it, at the time – but I’d seen it done with MIDI and some other early festivals – and assumed we’d figure it out. Those were the days when people would give you cash, and you’d work it out later.

Tell us about your first festival.

We held our first festival – the Yue Festival – in 2007 in Zhong Shan Park in Shanghai. It was a mix of techno, electronic and hip hop, all in this beautiful park. We got 4,500 people to attend – but I still lost another half million USD on it. But…it was launched.

"I feel the government was pretty tolerant of festivals before, but now, are not such fans. It brings them more trouble than it’s worth."

Why did it lose money? It seems 4,500 is pretty good attendance for the first show?

We overspent on talent. My philosophy was always to give the audience a great show – spend on great artists and production values. Our competitors were using local talent. Their talent costs may have been close to zero, actually (Midi was offering festival stage space for their affiliated music school bands). Our ticket price was 280 RMB, which was actually a pretty hefty price at the time. But we just spent way too much on talent.

I remember struggling with the decision in the first year to pay an act US$250,000. I wavered, but in the end, it was an emotional decision. I wanted to make the festival great. Was it worth the money? Nah.

In retrospect, I realized they had about five fans in China. After that, I learned to start using data.

What about the role of the government? Were they supportive at the beginning? And did it change over time?

We never really had any government support. We launched our festivals kind of “despite” rather than “because” of the government. In a way, it was better for us. As soon as the government is on board, things change. So, for me, it was fine.

A change in the market occurred when EDM started getting big. The authorities realised the genre was presenting an image they weren’t keen on. It was like promoters were almost taunting the powers that be. China decided they shouldn’t be enduring this, and the door slammed quite a bit. I feel the government was pretty tolerant of festivals before, but now, are not such fans. It brings them more trouble than it’s worth. So, this has changed things, where now, a degree of government support is probably necessary to make something happen.

Those were boom years for growth in festivals in China. How have things changed?

China is a very different place now from 2005, 2007. For me, after 26 festivals and creating multiple festival brands, we called it a day. It’s become a very challenging business. I lost about US$2.5 million of my own money in 2017 and 2018, which was very painful.

The problem is, the market is so over-competitive. Once you hit on a good idea, there is limitless money that people will throw at it. It becomes a feeding frenzy. Look at the shared bike business, as another example. Just too much money chases the idea, and the quality of products denigrates.

We raised money in 2015 from Alibaba for our Concrete & Grass Festival. By 2017, when Ultra entered the market, it was just oversaturated. The market wasn’t rational. There were over 600 festivals in China by then. Just cowboys trying to cash in. Whoever could raise the most and last the longest was going to win. My small investment couldn’t stand up against the massive influx of cash across the country.

I believed our heritage and relationships with artists would enable us to compete. But in reality, it was a need to go big or end it. People didn’t have an appetite for medium-sized events. We created some beautiful events and even more beautiful communities of music fans along the way, but in China, the festival-going audience just doesn’t last very long, unlike in the West where people start going as teenagers and continue through to old age. As an example, we had a kids area at Concrete & Grass – in the first year, it was just my kids and their expat friends, but by year four, a decent number of Chinese families had realized it was a great experience for their children. But these wonderful people were the absolute minority. I don’t believe there are a whole lot of Chinese parents that would consider a music festival a safe space for their kids. The appetite just isn’t that strong.

We are still alive. We are re-inventing ourselves. But we need to adapt, like anyone else in the market. The festival market just doesn’t make sense these days.

But you did try to chase this for a while, before realising it wasn’t sustainable?

Yeah. We got lured into spending big for artists. We spent $1 million on two artists in 2018 that didn’t sell any tickets at all. It was against my better judgement, but this was the race for big names. The industry was just so over-stretched. We lost a lot of money.

"We spent $1 million on two artists in 2018 that didn’t sell any tickets at all. It was against my better judgement, but this was the race for big names. The industry was just so over-stretched. We lost a lot of money."

Let’s talk about the skills needed to be a music festival entrepreneur. Did your background as a DJ help train you for this?

Absolutely. I chose the business of promotion. As a DJ, you need to learn the art of promotion. The skills I learned from about 18-21 years old as a DJ were crucial in the early years. You need to be a self-starter; nobody else will do it for you. You need to learn to make friends that can help you along the way.

Do those skills still serve you?

Over the years, you lose connection to the new generation, and how the kids discover and consume music. So, you need to rely on younger staff. I’m 44 now. I have no idea what 19-year olds are into, how they operate. My “lessons” from being a DJ were about posting flyers for shows, and where to find the best vinyl records. It’s irrelevant now. The world has changed so much.