Features

Features

Laurent Garnier: “If I only played classics I’d feel like a jukebox”

Laurent Garnier speaks to Manu Ekanayake about the importance of playing new music, French police cracking down on ravers, and his feature-length film Off The Record

You can’t talk about French dance music and not mention Laurent Garnier. This titan of Gallic techno has more than earned his OG stripes – his career dates back to before Daft Punk and the French Touch school of filtered house in the '90s; before Justice got everyone moshing to indie electro in the 2000s; and way, way before anyone even thought of putting the word “business” in front of the word “techno”.

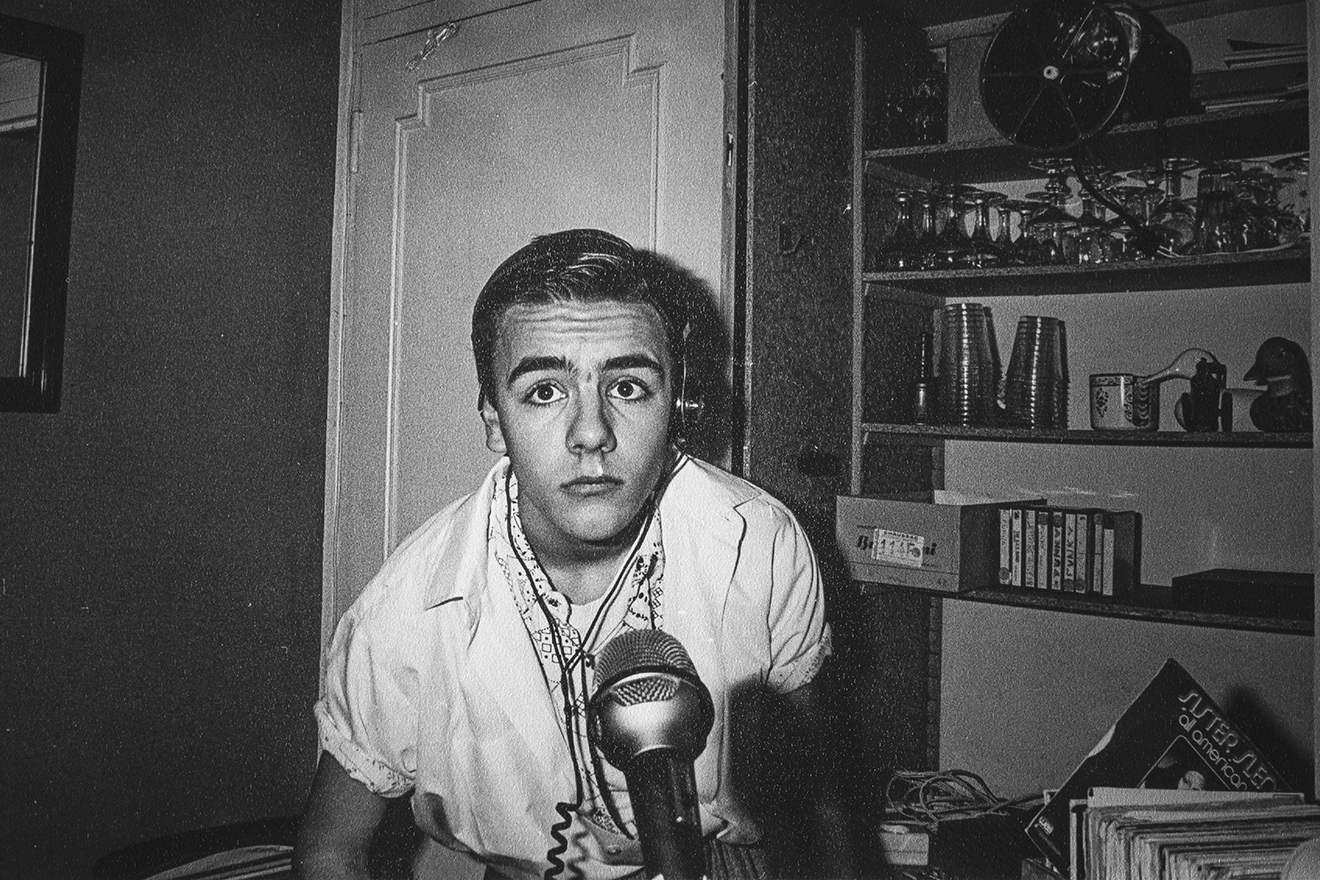

Garnier’s DJ sets are always emotional, even when he’s playing at the harder end of things. And he’s forever open to bringing new sounds to techno and bringing new artists through too. In fact, he’s still as fascinated with playing new music as he was when he started out playing his first professional DJ set. It was at a club called The Haçienda in Manchester, maybe you’ve heard of it? Yes, France’s most well-known DJ started out playing in pre-Madchester '80s Manchester, having come to the UK to work as a waiter in the French Embassy after he’d finished culinary school. He then followed a girlfriend up to Manchester, having been obsessed with music and clubs since childhood.

Read this next: The story of techno is being explored in a new documentary

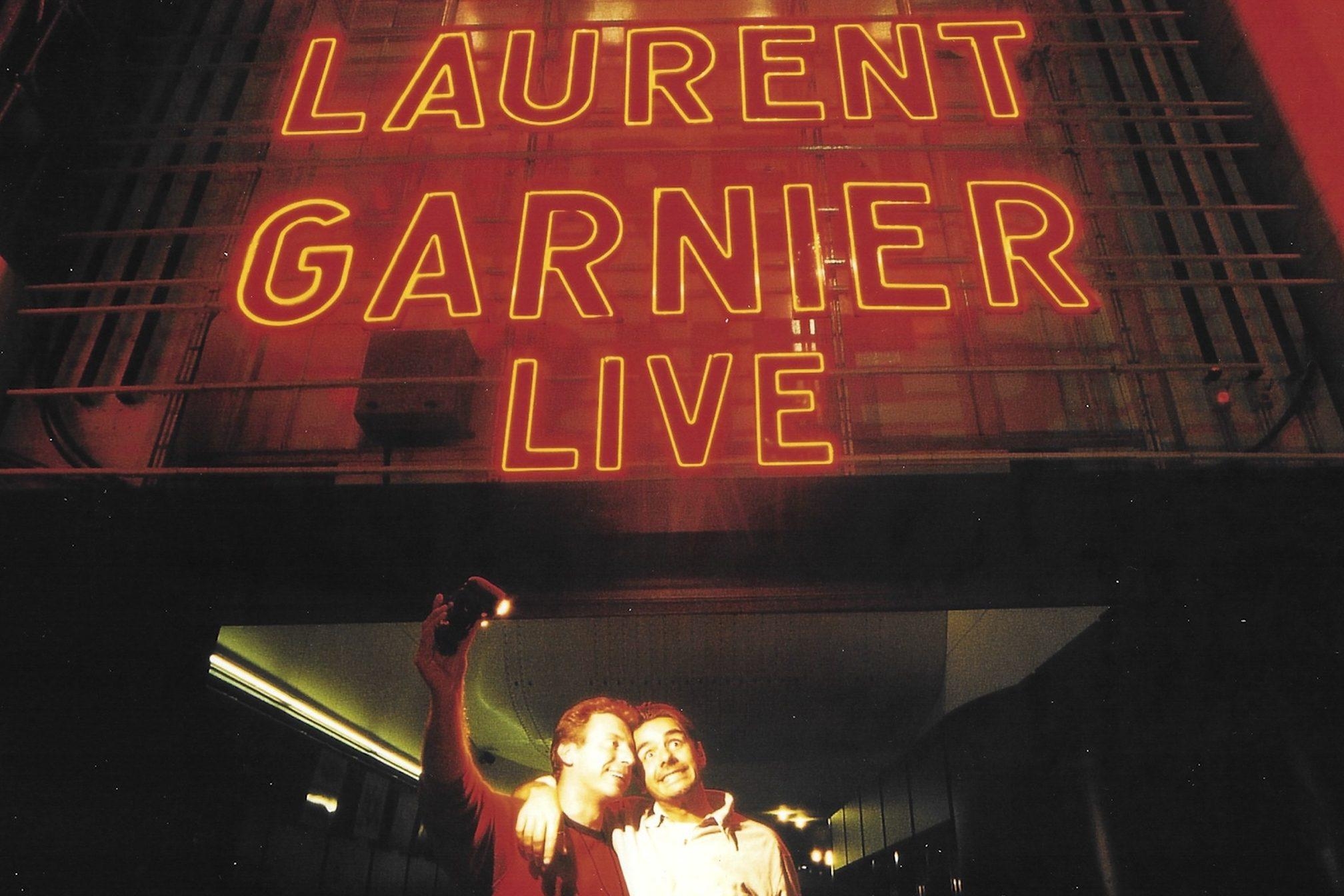

If this sounds like a long story then you’re right – and it’s a story Garnier is finally telling himself, with the aid of his friend and director Gabin Rivoire, via their new documentary, Off The Record. It came out this month in the UK and Ireland via Doc’n Roll. Garnier tells the story of his life in music, covering a lot of ground in an hour-and-a-half in the kind of uber-enthusiastic style that will be familiar to anyone who’s seen him DJ. Garnier is up there with the most passionate advocates of dance music culture Mixmag has ever interviewed. If countries had club culture ambassadors – and they should – he would be France’s.

So how has it felt to be promoting a film rather than your music?

Well, we've toured a lot with the documentary and I think the fact that we do Q&As afterwards is really significant. The film came out last year in France and we've done maybe 30 or 40 different cinemas there. And then it came out on Canal+, which is big French TV channel, in early December. They said they'd keep it for three months but it's still there, so it must be doing quite well. We're still asked to do screenings and Q&As in France and I actually did one in Brussels recently too and it was full. We'd love to hit America with it. But so far the reaction from people has been amazing. Like my book Electrochoc, which started slowly but is doing really well now. People took it in a nice way and if the film can do the same it would be great. It was nice for me after the confinement of lockdown to start meeting people in the cinema. People would get very emotional afterwards as they hadn't dance for a year-and-a-half. And it was nice to see the crowd, in a different setting, but the emotion was still there.

Read this next: 6 of the best dance music documentaries to watch on Netflix

I love the way you start the film, using that French version of the classic Tony Bennett song, ‘The Good Life’ and this nice pastoral scene.

I think it's the original song, I think Tony Bennett took it from Sacha Distel. [Laurent Garnier is right — it's 1962’s 'La Belle Vie' by Sacha Distel, later covered by Tony Bennett]

But this is the magic of Gabin Rivoire, the director. He's not a music person. He's not at all into techno. He's not involved in music in general. For him, music stops when Ziggy Stardust died on stage, so in the '70s. That seduced me: I liked that he didn't know about our music; he has fresh eyes. And I chose him because I co-organise a small pop and rock festival in the south of France, and since the beginning Gabin's been there with his camera: he made all the after-movies. They're all a bit odd and quite poetic in a way. You feel something different about his way of filming music and that is what I liked. When he did the first edits it was a different song but still an Italian crooner. So I told him we should use a French song as it's a film very much about France. But he said "Everybody will expect us to start with decks and people DJing to a crowd. We're gonna do the opposite because I think it will set the vibe from the beginning." And I loved that right away. He dares to do something different and I love that.

So how long did the documentary take to make?

It took four years overall. It took that time because Gabin's never made a film before so he couldn't understand why I chose him. He was making corporate films to sell kitchen tiles, ok? So first I had to reassure him he was the right person to make this documentary. I suggested we should go on the road together and he was like "Why me? There are thousands of people you should choose rather than me." And I said "But I like what you do and I'm sure you're able to do what I want – I trust you."

Also, we were not a professional team with a producer and a deadline so were completely free to do what we wanted. This meant we weren't focussing on one thing; we were focussing on 20 things. We went on the road for about two years but we still didn't have the central pitch. We knew we wanted to do something around the story of house and techno but that's obviously a huge topic. But Gabin came up with a synopsis like two years after we'd started. So by this point we had enough images to make the film! But we still needed more interviews and more film for the topic we'd finally decided on. So by this point it's three years. Then we had to edit it, then COVID happened and that took a long time to get a production company that would work with us. This all took far longer than expected because there was no structure behind it. But I'm very happy we did it that way as I'm super happy with the result. It's very much who I am.

I think it's good with the people you interview there's people who are well-known DJs of course, like The Blessed Madonna or Carl Cox, but there's also industry faces like Georgia Taglietti, who worked with Sónar on their media side for 25 years, who are perhaps not known to most clubbers...

I think if you tell the story of Chicago or Detroit it's better to be told by the originators. Jeff Mills or DJ Pierre, but I wanted to have Rosh [now known as Works Of Intent] as he's the new guy in the scene and everyone knows I've signed him on my label and I'm a big fan. He’s got amazing ears so he can hear things in music I never could, as you see in the documentary, plus he’s such a thoughtful guy – he can write fascinatingly on music, race and culture and he’s just a fantastic artist. He’s one of the ones who should make a difference. I've pushed him and we have a great relationship. Because if you want to talk about the inside of the scene, you need to talk to the right people. So if you want to talk about Belgium then I had Peter Decuypere who started Fuse and I Love Techno festival because he knows his shit. And so it made sense to have Georgia there for the same reasons.

Because this documentary is for both sides: the one side that knows about techno, who will see things they've seen before and understand. And then also for the others who know nothing about techno. So we can give them a little of the social aspect, the political aspect and more. Telling them what happened and where it happened. We wanted to cater for a much wider range than just for the techno world. I mean that's the way I did my book, Electrochoc, I wanted it to cater for both sides. We didn't want it to be too anal about the whole thing, shall we say? [laughs]

OK well on the subject of the world outside dance music, Beyoncé and Drake have just saved house music – according to to a lot of lazy headlines at least – so what do you think about popular artists referencing dance music?

What? I don't even know what you mean? [Mixmag briefly explains that Beyoncé's put out a new house track, 'Break My Soul', while Drake's recent album, 'Honestly Nevermind', is very house-influenced] Well David Guetta did it 15 years ago! I mean David Guetta changed things. Even though he's on the more commercial side, he changed the whole perspective of R&B radio in America when he started to use hip hop and R&B artists with a house beat. So they've not invented anything new. This said I've not heard the music. R&B acts have done that for a long time though. But if we talk more about hip hop and rap, in France with the younger generation who love drill and trap, now they're starting to use house beats as well. They've understood the connection between techno, electro and hip hop and it's becoming obvious to them making music with a straight kick works for their crowd too, who are into both scenes. So I guess Beyoncé and Drake are doing it in a more commercial way, but the underground is still doing it too. It's nice to know that's happening. But the links between the two scenes have always been there since day one because of electro music. I mean, look at Detroit, when they opened new record shops there, they would have an electro section to appeal to people who listened to hip hop. So they'd get the link between hip hop and techno. It's always been there.

Read this next: Why are superstar DJs so keen to reconnect with the underground?

OK, well to go on to a different topic now, how was COVID for you? I mean I know you had to write a letter to the Minister of Culture in France, so can I ask you about that?

You know pre-COVID whenever we, the older generation of techno, met the younger guys, they'd say to us: "You guys had to fight for what we have now. But when you won all those fights, we don't really see what we have to fight for?" And we'd always say: "Find your fights, because there are definitely many things to make better. It doesn't have to be about the techno scene, but you can use the scene to highlight it." And in a way it was true. We did win all the battles. But during COVID when we heard the French Cultural Minister say that club culture doesn't belong to her ministry, but instead to the Interior Minstry, we said "What? We're not part of culture?" So I started to question myself. "Why did the government give me this medal in the first place? Does it not count now there's a new government? Have we taken three steps forward and five steps back?" So I had to write this huge letter to the Minister of Culture basically asking what the fuck was going on. We all realised that we shouldn't take anything for granted.

Did it take you back to the '90s when techno was badly considered in France and you felt like public enemy number 1?

It did in a way because last year was very hard for the techno scene here in France. Besides what the Minister of Culture said, there have been a couple of parties where the police came and smashed all the equipment. This was on the 14th of July when the President has some techno DJs in his house to entertain his people. But at the same time as he said he loved techno the police were raiding parties and smashing equipment - rented equipment, not even stuff that they owned. Speakers, amps, man we really felt like we were back in the rave days. What the fuck was going on? It was quite violent here. The press and the police have always been quite hardcore with us; we're always seen as a druggy scene or whatever. Last year it regressed a lot and yes, we did feel like we really hadn't won that many battles at the end of the day.

Read this next: 20 iconic illegal rave photos

OK if we move away from politics then, can I finally ask how important is it for you to still be playing new music after all this time?

It's vital. It's the essence of my job as a DJ. If I only played classics I'd feel like a jukebox. That's not what I am, that's not what being a DJ is. The job is to search for the new stuff that I feel good with. If I just focused on classics I'd never have discovered Rosh, or hundreds of other artists I've discovered over the years. This is what our job is: if we're not here to play the new stuff then who the fuck will? The radio won't do it, that's for sure. You know you can play a classic record but only as the cherry on top of the cake. Then I'll do it and we can all enjoy that special moment. But otherwise, no. I wouldn't consider myself as a techno DJ if I was just playing old music. I do like playing classic sets but I announce them as such. "Tonight I'll do something different." And then I'll dig out some things that are not super well-known. Our job as DJs is to search for the new people and give them some space.

Laurent Garnier: Off The Record is out now via Doc’n Roll, watch it here

Manu Ekanayake is a freelance writer, follow him on Twitter