Interviews

Interviews

Survival of the Fitz

Adam Wright chats with Jane Fitz as she returns to Hong Kong, the city that formed her as a DJ, with her new residency at 宀 kicking off this Saturday

Jane Fitz is one of the most respected DJs working today. Famously eclectic and completely authentic, Fitz is a regular at events such as Dekmantel and Amsterdam Dance Event (ADE), but you’re just as likely to see her at a squat party or an obscure little club with a great soundsystem.

This is because Fitz has never forgotten her roots—and these were laid down during the wild 1990s in Hong Kong, a period that shaped her future as a DJ.

Ahead of the first gig in her new residency at Hong Kong club 宀 this Saturday (February 15), Fitz talked about those heady days in Hong Kong before the handover to China, her marathon sets, her disinterest in success and why she will ever only play vinyl.

With your new residency at 宀, and your return to regular gigs in a city where you were DJing around three decades ago, do you feel that you’ve come full circle?

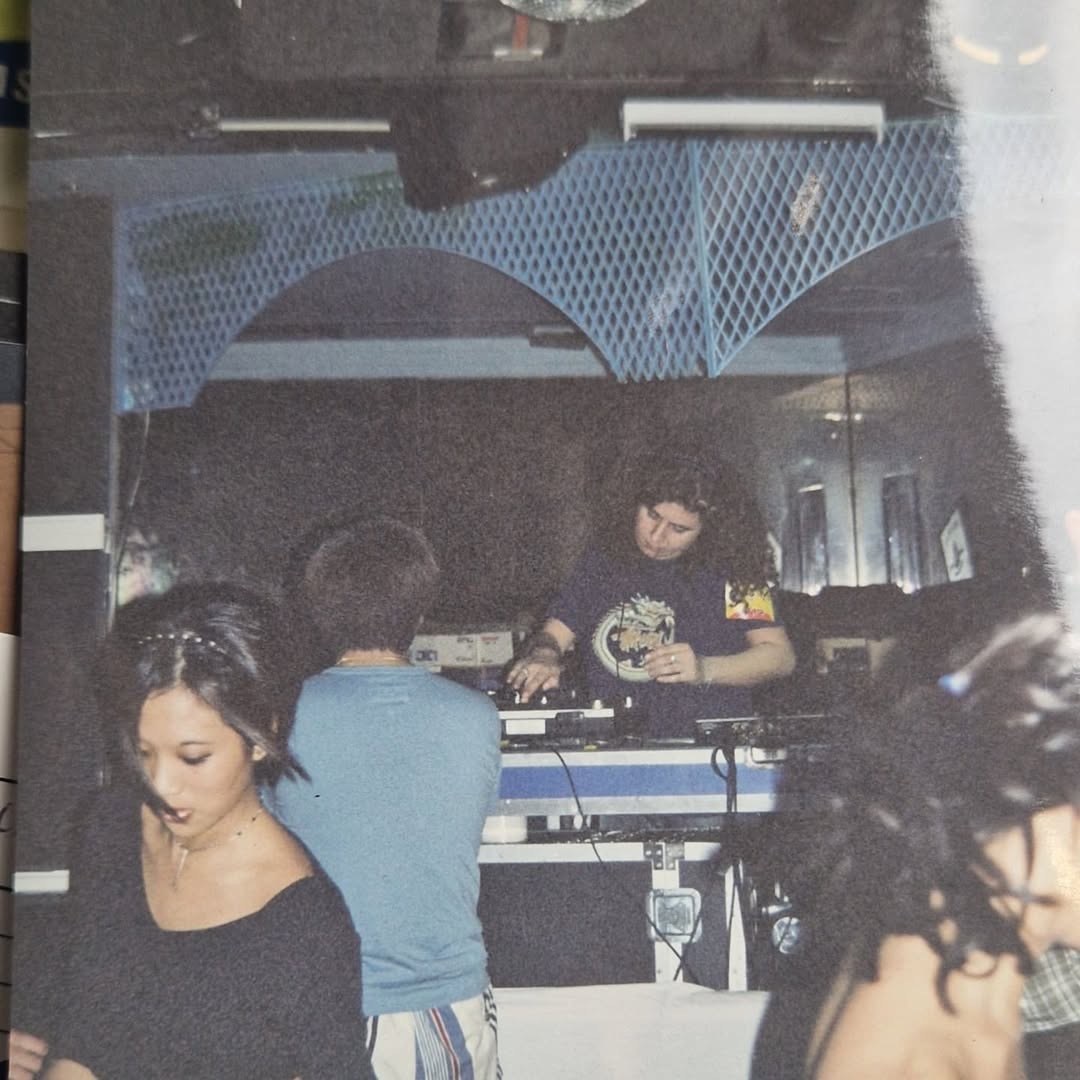

Yeah, in a way. I had been DJing before I moved to Hong Kong, but I hadn't worked out how to mix. I was playing rare groove, hip-hop, jazz, that kind of stuff—you didn't really need to mix it. But my flatmate in Hong Kong had a set of decks and I started learning, and immediately friends started booking me. My friends ran a party at the CE-Top club called Robot (they are some of the guys who went on to launch Clockenflap) and I became one of their residents. We were into the same music—deep house, early British tech house, deep techno. And then I started getting booked at bigger venues like Jimmy's Sports Bar and Bar City. I remember playing at Bar City when Carl Cox came over.

About a year after I was really getting going I had to leave because I didn’t have a work visa. In the past few years, I started hearing about this club in Hong Kong, which is obviously 宀. I don't remember how the first gig there came about. It was around two years ago I guess, but it was an all-nighter and it went super well. We all got on and everything was really nice, and they just said, “Tell us when you're coming back. You’ve got a home here now”. I’d been back a couple of times before to play at friends’ events at venues like Yumla, which is now called Oma, but this was the first time I'd been booked in Hong Kong as a visiting overseas DJ, so it was pretty crazy as I did all my learning here.

So that’s how the 宀 residency came about?

I saw the guys from 宀 again at Dekmantel and maybe we spoke about it then. I don't remember the details, but I said, “Of course I want to be a resident”. Hong Kong still feels like home because I did my transition from playing jazz and so on into more electronic music like house, trance and techno in Hong Kong. So it felt very special to be offered this.

What memories of Hong Kong in the 1990s have stayed with you?

Very hazy ones, because I was partying all the time. I remember that the music was never actually that good, but I loved it because we were all partying together and it was a nice community. We were having dancefloor epiphanies every weekend. I formed friendships that I still have after almost 30 years. I learned about after parties, I learned about playing long sets, I learned loads of things about building a night, controlling a night. It was an unusual time because you had this mixed crowd that couldn’t have existed anywhere else.

I lived in Singapore before coming to Hong Kong, but Hong Kong was much more advanced, maybe because there were so many British expats who'd come over with their record bags. It wasn't very middle class; it was just ordinary people. You’d have everyone from maids to High Court judges on the dancefloor.

Why did you leave Hong Kong?

Because of the visa situation. I never had a full time job in Hong Kong and was always a freelancer. I was working as a journalist and worked at HK Magazine for a year as entertainment editor, but by the middle of 1998 I needed a visa. And I was like, “Do I really want to get a job here?” I'd never had a proper job. In the end I came home, even though I wasn't ready.

Back in the UK, how did you establish yourself in the scene over there?

Very slowly. It took 20 years for anyone to really care about what I was doing. From 1999 to 2009, I ran my own party called Peg, which was a warehouse party, and this led to bookings at other events. This was before social media before anything was really online, so I was just working hard, giving out tapes, giving out CDs. It was still a hobby. I was still working as a journalist, so I didn't need to make a living from DJing.

After about 10 years I started to get booked a bit more regularly. I think I got onto SoundCloud within a month of it launching because a friend in the US sent me a link, and that led to me meeting Keith Worthy from Aesthetic Audio in Detroit. So, I started visiting Detroit and started appearing at the Freerotation festival in Wales in 2010, but everything was very slow.

Read this next: Five ways David Lynch made his mark on electronic music

In 2012 you started the Night Moves series of events with Jade Seatle—is that when things really started to kick off?

If you plotted it on a graph you would just see a slow incline. I would say I started getting really busy and playing more overseas around 2014. Jade and I haven't done a proper party since before the pandemic. Back when we started, there were literally no parties that we liked in London, so we just decided to start our own. It was the most honest thing—just two mates who play records putting on a party for their friends.

Nothing was planned, there was no branding. But the fact that we haven't done a party in a long time has given it this kind of hallowed status. We're probably going to do one or two summer parties this year, but we don't court fame, we don't court the press, we don’t do listings, we don't advertise it. I'm even kind of against selling tickets online, but there’s no way around it anymore.

Your show on Rinse FM seems to have been another milestone and you became known for championing up-and-coming artists. What impact did the Rinse residency have on your DJ career?

All I did was play records that people gave me because I didn't just want to do a mix show. I asked myself how I could make radio more useful, not for me but for everybody else. I was getting sent loads of records and being given records when I was out playing, and I decided not to even play them before the show. I was just going to play them on the radio show for the first time and obviously that caught on.

I come from a background where people talked on the radio, so I talked about the records, talked about the labels, and made it feel more like a show. And that worked and people liked it. It was all about showcasing the records, helping young labels, helping young producers, using whatever profile I had to help other people.

Read this next: Madam X on "staying true to myself and drowning out the noise"

You’re still closely associated with Freerotation, but in recent years you’ve been playing at other high-profile events like Dekmantel and ADE in Amsterdam, and Dimensions in Croatia. You seem to be quite in demand now—is this what success looks like to you?

I don't care about success. For me, DJing has always been about playing my records, telling my stories, sharing what I like, turning my mates onto music that maybe they hadn’t heard. I don't really measure it or even think about success, because for me, it's just a part of my life and something I've done forever. That’s why I've never really put records out—because I don't care. I put out a few records when I had something to say, but after a while it became boring. I'm just into records.

Success for me is not having to go to an office every day, not having to commute, getting to hang out with my dog during the week. Success is being able to do something you love and not having to stop even when you’re in your 50s. On my deathbed I’ll look back and say, “Fuck, music's been brilliant for me because it gave me a really nice life”. I’ve been able to follow my passion and eventually make a living out of it. But in terms of fame and all that shit, I don't care. How many gigs you’ve got, how much money you got paid or how many people came—these things are irrelevant to me.

I played a squat party the other Saturday morning for a couple hundred people for hardly any money, but for me it’s really important to still do those kinds of things. Success for me is that I get to still play my records.

You seem to prefer playing outside surrounded by nature instead of in a club—what’s the difference?

The fresh air is number one. And there’s something to look at while you're playing. I like to smell the air and see trees and mountains. In a club, you see the front row and it's dark, and that's it. It's not particularly inspiring. The only thing inspiring about a club really is a good soundsystem, but when you're at a festival, so many other things can be inspiring. There are also organic elements in my music that feel appropriate to play outside in nature. I don't feel as contained as I do in a club.

Read this next: "I want to be a part of electronic music history": Red Pig Flower looks forward to another 20 years in the scene

Your sound is quite hard to categorise—how has it evolved over the years?

It's just an evolution of knowledge. When I discover new things, I want to play them. When I started, the music that I was really attracted to was jazz, which was what I was listening to when I was a child in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s. Electronic dance music didn't exist when I started collecting records—I was 15 in 1988. So my sound has evolved as music has evolved. I'm always discovering new sounds and am always looking for new records.

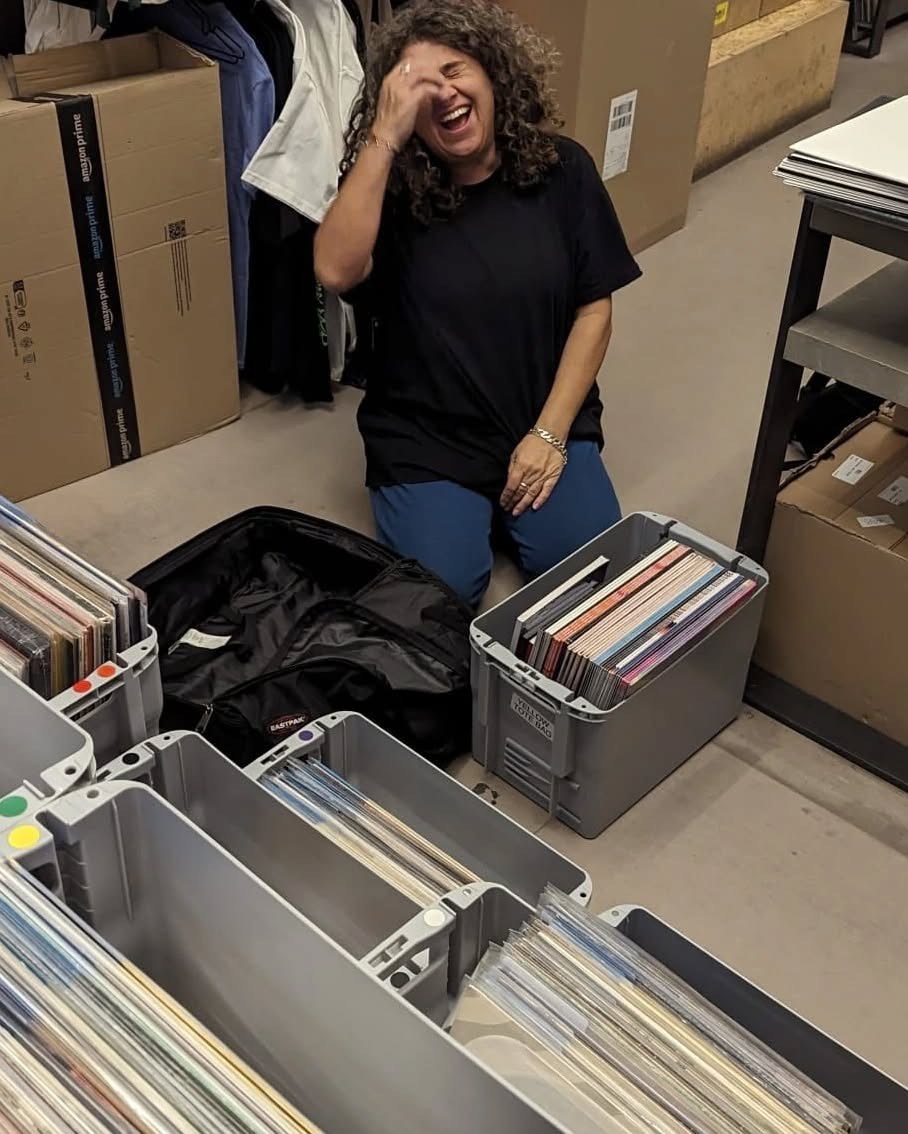

I'm not only obsessed with the past, even though I play a lot of old records, but that's because there's so many great old records and so few great new ones if you compare them. I have a fuck-tonne of records and I like everything. I can play ambient, techno, trance, Goa, deep house, breaks, electro, everything. I can hear the connections between them all and hopefully other people can too.

You’re also known for playing marathon sets. What’s your approach to putting these together and do you think this is becoming a lost art in a time when many festival sets are about an hour long?

I like to hear a DJ express themselves—how can you do that in two hours? If you're playing drum’n’bass, for example, you can’t play an eight-hour set because it's too intense, but I've done a lot of them. I've done eight-hour sets with two hours of ambient or two hours of downtempo at the beginning, because I have the space to do it. This allows me to explore those records and build up the tempo, and I'll be doing that in Hong Kong.

I'm not starting out with ambient in Hong Kong because I don't have the room in my bag for those records—I have to tailor my sets around what I can bring. But the process doesn’t change whether I'm playing a three-hour set or an eight-hour set. It's just that I've got more space. I never really know what I'm going to play. I just know what records I want to hear and what records go with those records.

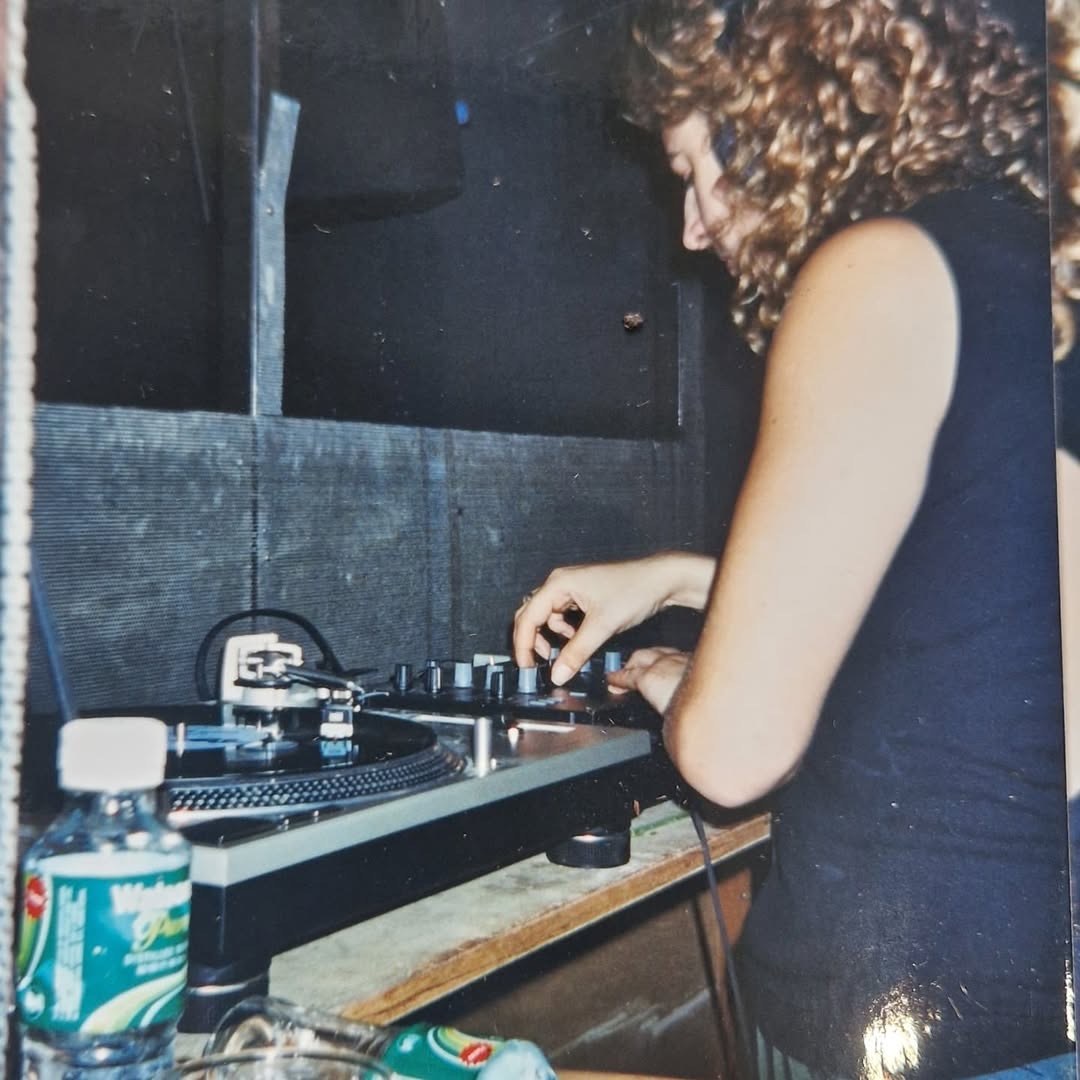

You still strictly play vinyl—why have you stuck with this format for so long?

My bad memory, to be honest. If I don't have the visual stimuli of a record, I haven't got a clue what it is. I don't know what anything's called. I barely know the artist names, but I know what the labels look like. There’s something very physical that I enjoy about the mixing process. And I like the fact that you get a break every record to turn your back on what's going on, to look over your records, have a drink, have a smoke, whatever. When you play digitally, you’re standing there looking at the crowd the whole time and I find that exhausting. When you play records, you get to turn your back on people and you can't do that with any other format. And you can't lie with records. The soundsystem cannot lie, your mixing cannot lie, your tune selection cannot lie. Everything is really honest because there's no other option.

Read this next: A recollection of unexpected finds & slices of serendipity at Wonderfruit 2024

How often can we expect to see you back in Hong Kong?

There isn’t a fixed schedule. The 宀 guys have just said that any time I’m coming through, just let them know. Ideally, I'd love to come every year, but I don't know if that's possible with my schedule. It’s been a joy coming back to Hong Kong over the past two years. I get to see my old friends again, I get to hang out and reacquaint myself with the city that meant so much to me growing up. I hate this phrase, but I'm giving something back, because Hong Kong has given me so much, not just in terms of my DJ development, but also my personal development.

Hong Kong is an important cornerstone of my life. I've gone overseas and done the hard work, but now this is for you guys. Everything I’ve done has always been based on my time in Hong Kong—the sounds, the air, the smells. I used to live on Lamma Island and take the ferry home after parties in the morning. It would be like 45 minutes to have my little chill moment and that sticks with me even now. That feeling of coming out of a club and just chilling and being on the water—those things still feed into what I'm doing. Now even more so because now I get to do it in Hong Kong again. And 宀 is a great club. It's very well run and technically perfect. The soundsystem is excellent. The crowd is really nice, really receptive. Some of my old friends will be coming, even though they didn't know about the club before, which is crazy. So, all of that really does bring me full circle.

Adam Wright from Omni Agency is a contributor to Mixmag Asia; follow Omni on Instagram here.