Interviews

Interviews

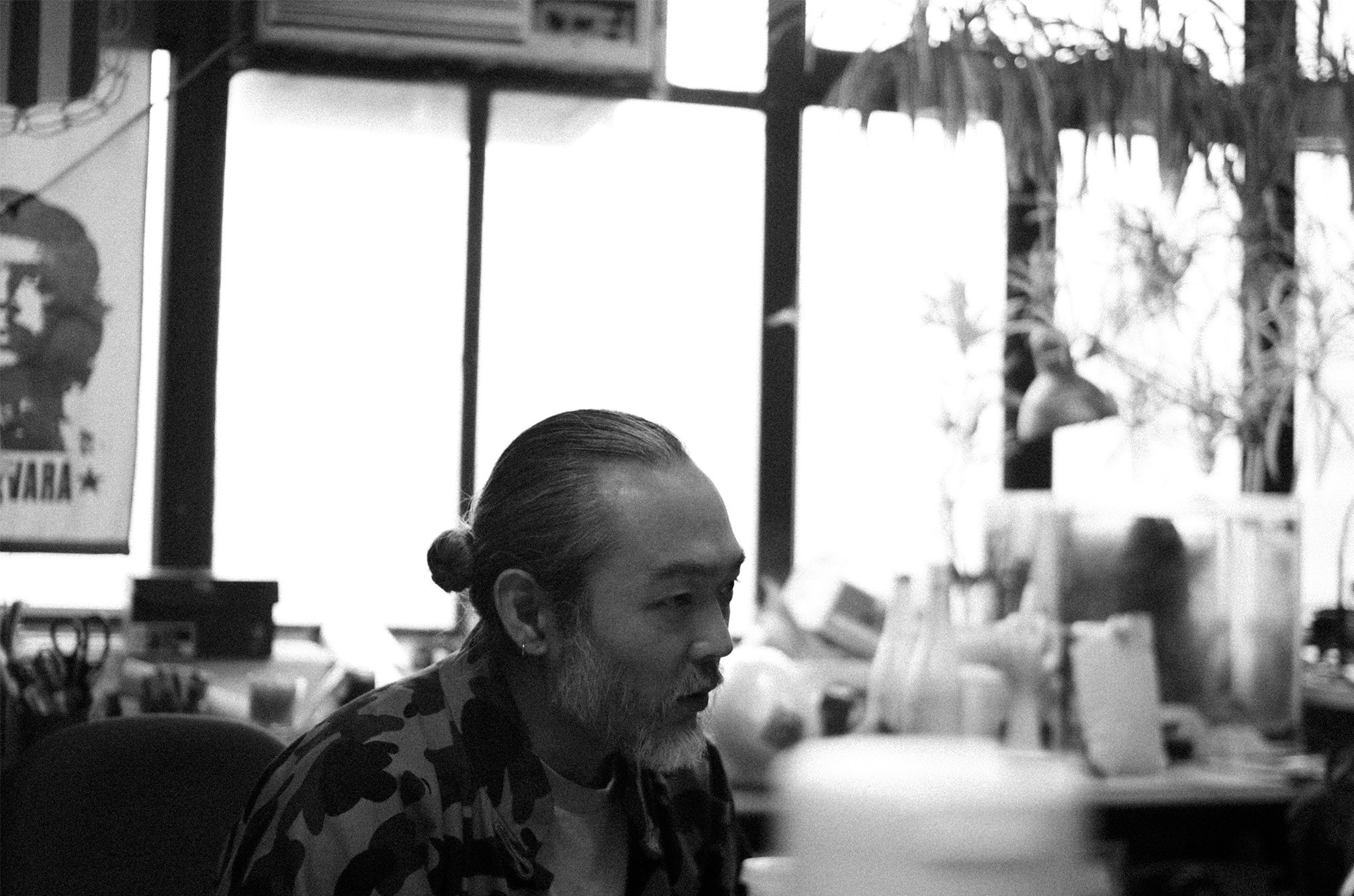

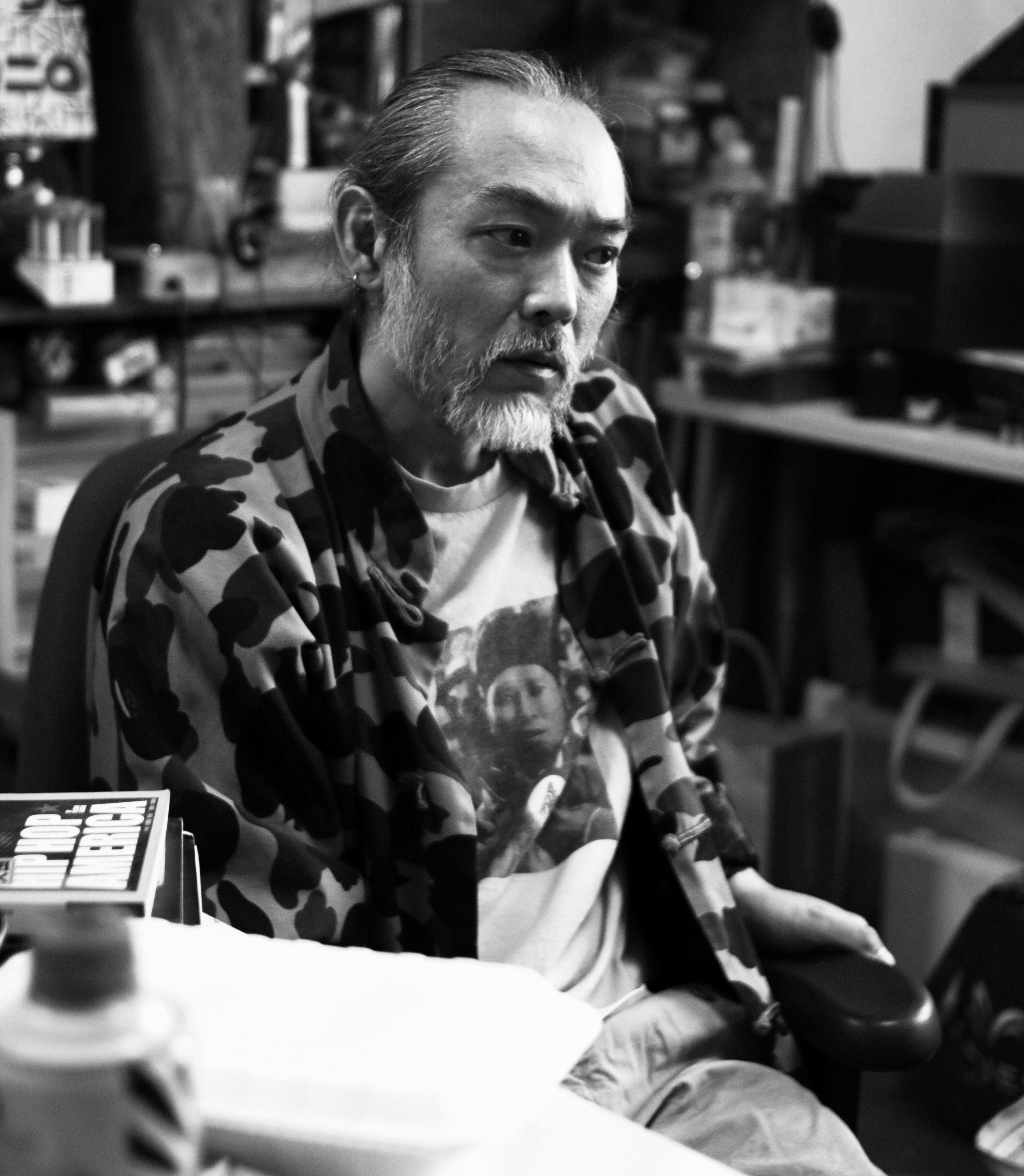

Hong Kong’s MC Yan throws up graffiti & hip hop knowledge

“Do not be restrained by formality. Be sincere to the art form.”

LiFTED got a chance to sit down with Hong Kong hip hop and graffiti pioneer MC Yan for our first edition of Graff - an interview-based feature where we talk with some of the most prominent figures in the Asian graffiti and street art scenes. Along the way, we will be learning their history and picking their brains about modern graffiti culture.

Visit LiFTED Asia for the latest on hip hop in Asia.

THE GODFATHER

‘The Godfather’ is not a title given out to just anyone. The multi-talented MC Yan is an artist who was the first person to effectively introduce hip hop to Hong Kong in the 1990s. As the wave of hardcore hip hop acts like NWA, The Notorious B.I.G., and the Wu-Tang Clan stormed the consciousness of American youth, it was still quite unheard of on the other side of the globe.

This was about the same time when Yan had his first taste of graffiti and hip hop. “I was first exposed to graffiti in a relatively small town in France when I was studying visual arts. Graffiti was a hit underground culture popular among young European artists. My fellow classmates were very invested in seeing the emergence of a new art form. In 1997, I returned to Hong Kong with the ambition of starting my own crew, the CEA. There were some tags and throw-ups scattered around underground tunnels in Tsim Sha Tsui, which I believe were done by foreign artists who stopped by Hong Kong during their travels, but I think we were the first local crew to explore this art form in Hong Kong’s concrete jungle."

STYLE & TOOLS

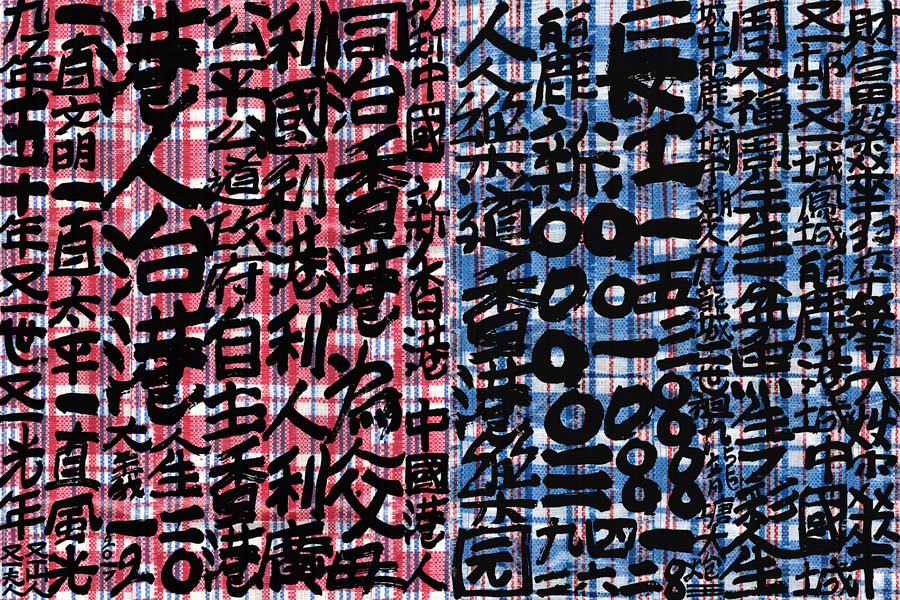

As one of Hong Kong’s OG graffiti artists, Yan is clear about his creative process while developing his graffiti style. “I am very impromptu but consistent with my style. I have been doing tags over the last 20 years and using Chinese characters has always been my style. Originating from hieroglyphs, Chinese characters have this alluring structure that is bold and elegant, yet simple and powerful. My three references are from traditional Chinese calligraphy, which is a beautiful art form on its own, adding on modernised typography - and my own creation which is about using Chinese characters inversely. It all just came together when I incorporated them into a system which I have based my style on ever since.”

Yan shares his immensely distinctive approach to wall painting. “I am quite adventurous when it comes to the paint I use. Neon-like, fluorescent colours with high contrast are my go-to. I did research on the chemistry of these paints and experimented with an array of chromatic, explosive and luminous colours. But you know how I got all these peculiar paints? I have my own supplier and take up the role as a tester. I used semi-transparent paint on skateboards for a recent project. Another favourite of mine was using paints that could only be seen under UV lights.”

Using stencils as a medium for creating street art has always been controversial among graffiti artists, as some consider it to be unauthentic. Yan has this to say, “Street art gained popularity because it is friendly. Some artists prefer to go off in a more aggressive fashion, but I think it is very much up to an artist’s own will. Authentic graffiti is about working the piece at the right location and not getting caught afterward. That’s what’s aggressive about doing street art, yet with the rise of social media and the desire to go viral, many might choose a path that could get their pieces more widely shared. Graffiti has always been about being seen. But in the end the means do not matter. What matters is how smart and impactful the art is when it comes to inspiring its audiences.”

Yan continued, “I do feel like many artists are missing the point. I want people to understand that graffiti is about aggressiveness. It is about surviving on the street. It is OK to do softcore graffiti for an educational purpose, say introducing it to a wider audience. In that sense, it has to be very friendly, but that does not mean you can’t fool around with tricky elements. Try something new! Do a hidden drawing, or a live painting. There is always a clever way to execute your vision.”

LEGAL PIECES

As graffiti is slowly and steadily taking over Asian alleys and corners, fashion brands and entrepreneurs are taking notes from artists, as shopping malls and even the government in Hong Kong try to curry favour with the youth. Everyone from ad agencies to commercial buildings have joined the quest in recruiting renowned artists to do mural paintings, causing a dilemma for some old school rebels - is commissioned graffiti art on buildings and brands as valid as street graff?

“What they are doing is graffiti-style decoration, or let’s say in a modest way, wall painting. It’s like graffiti castrated into substance-less illustrations. We graffiti artists witness crimes and seek exits whenever we are working on pieces. The most problematic concern I have with modern graffiti is that many outsiders or even insiders consider this art form as a symbolic gesture to apply something from the West to illustrate capitalism with globalisation. Graffiti, and hip hop in general are all by-products of the free world. Essentially there is a conflict between doing legal pieces and doing graffiti, as legal pieces are highly sanitised. Graffiti was given birth from a depressed environment. Objective measures such as the size of the piece should not matter, because they are not depicting reality. At the end of the day, I think it depends on whether we have provided enough opportunity and resources for the younger generation to be expressive via this art form.”

KOWLOON EMPEROR & PLUMBER KING

While Yan is widely considered to be the pioneer of Hong Kong’s graffiti scene, he still speaks highly of those who paved the way for him. “I might be from the first local crew, but predecessors like Uncle Choi and Tang Kee extended the boundary and the landscape for me.”

Here Yan refers to ‘King of Kowloon’ Tsang Tsou-choi and ‘Plumber King’ Yim Chiu-tong, both local legends who were arguably the first to popularise street art to the general public. Before his death in 2007, The King of Kowloon dominated the streets with his prolific calligraphy, describing his and his family’s reign over the expansive district. His persistent and determined calligraphy tagging, despite the continual scrubbing by the government earned him a mythic cultural identity, so much so that people began to steal the metal electrical box doors and other public surfaces he wrote on, and they would eventually fetch six figures at contemporary street art auctions.

Another prolific figure is the Plumber King, an actual plumber in his 70s who has been amusing pedestrians with his iconic 'calligraffiti', as he simply paints his sobriquet and contact number as his own version of low-cost outdoor advertising. While it started off as a promotional stunt, the Plumber King has grown in popularity and became a cultural phenomenon. Yan, ever the curious artist, has had several encounters with the two veterans.“

The key of Kowloon King’s work is his ominous spacing. He could always find ways to fill up every inch of space with his scrawled calligraphy, which made it very appealing visually. Same with the Plumber King, and his outlined colours. I had several conversations with him, and you could tell he enjoyed every single detail of ‘vandalising.’ Nothing could stop him from doing his work. Not the cops. Not the weather. You know he has been fined several times, yet that’s not stopping him either. He strolls around with his scooter and ink in the back. Their pure intention and expressive minds were not confined by any commercial preference, and this is what makes both their works original and distinctive.

FUTURE GRAFFITI

Speaking of genre-bending, Yan was also involved in an unprecedented street art project with world-renowned Graffiti Research Lab [GRL] when they were touring in Hong Kong in 2007. Established in the early 2000s in the Bronx, GRL is an experimental group led by graffiti artists with engineering backgrounds. Their primary approach is to create street art with a new medium - lights and lasers. Although it is not as long-lasting as traditional spray paint or stencil art, lights and projections in an outdoor setting are more immediate, with direct visual and interactive impact. Titled ‘H$ONG K$NG,’ Yan and GRL managed to project huge laser-formed images and calligraphy on walls across Victoria Harbour with real-time interactions.

“When people are suppressed from doing a certain art form, they will seek something new. It is only human nature to express our own feelings. It’s the circle of life. Graffiti is a meaningful art form because it interacts with the public via urban surfaces, but I am always willing to look for more inventive stuff, which is why I worked with Graffiti Research Lab. They were top-notch engineers with inventive, perky minds and love using Hip Hop as a form of cultural contribution.”

“When mural arts are deemed to be illegal, we fight with light graffiti. And there were a ton of issues we had to overcome: the logistics, the severe light pollution of Hong Kong, how to engage the crowd without it getting too chaotic. And then there are surveillance systems on every street corner! Yet we still managed to do large-scale light graffiti installation From Hong Kong island to Kowloon side. That was 15 years ago! We certainly have the technology to do it from country A to country B. That will be a new form of future graffiti.”

As a true pioneer, Yan is respected and admired by every young artist in the Asian graffiti scene, but the humble master has mad respect for these local kids too. “I like Devil and Dream. They have evolved tremendously with their skilful techniques. With these rising stars, one day we could cultivate a beautiful Hong Kong landscape. Well, one thing is lacking in the current Hong Kong scene though - subway and railway art. Trains are clean AF in HK, but again with all the surveillance around, getting up on trains is quite a challenge.”

ELEVATION

When talking about the recent growth of Asian Hip Hop and the hype around it, Yan invited us to watch the 1982 Hip Hop classic movie Wild Style. “This film is as authentic a fictional creation as any you will find, in terms of depicting the realistic hood life, and the struggles young people faced in those early days of the culture in New York. I think it has a lot to do with how Hong Kong’s youngsters are moulded. Many of them are convinced that in order to be successful, one has to fulfil the role of being a financially constructive member of society and have respect for authorities at all times. Life was different for New York kids in depressed parts of the boroughs back in the 1980s, and most of the time we are just mirror reflections of our parents. You can always trace the structural formation of society solely from the behaviour of teenagers.” Yan continued, “Take a look at New York in the 70s and 80s. Hip hop is not just a style or fashion. To those kids, hip hop is the primitive urge of young African Americans to seek their roots while struggling with their self-identification after generations and generations of suppression. Throughout their journey of self-exploration, hip hop is no longer just a lifestyle, but also a means of alternative education. Hip Hop is how to strive for space and meaning in the urban setting. However, hip hop is also based on concrete and, and is structured by urbanism, and could easily be replaced.”

Finally, we got to ask Yan’s insight on the million-dollar question - what elevates Asian hip hop?

“What makes a city fun is the energy teenagers channel via their playful thoughts and youthfulness. They grace the world with creativity, and don’t care wherever it’s old-fashioned, old school, or new school. Just true school. Be genuine and true to yourself. I had this weird encounter with an old granny from Northern China a while ago. It shocked me to my core as she expressed her pride to see her grandkids wearing baggies while they have no knowledge whatsoever about Hip Hop. These people don’t have the slightest idea of what they are appreciating.”

“Way before the hit TV show, The Rap of China, there was an underground rap battle contest hosted regularly in China called Iron Mic. They had their own Chinese Hall of Fame, freestyle battle, and everything. Hip hop should be inclusive and embody the diversity of the various pillars of the culture, while exceeding the boundaries and geographic limitations of nations. It’s true that every Asian country has its unique cultural presence. Nonetheless, the way I see it, in the near-future hip hop will be a medium that works internationally as a crucible for diversity. Language barriers aside, like the infamous Universal Zulu Nation suggests, hip hop is about hood, and hood is not bound by the concept of nations. It is a cultural exchange of hood lives, with inclusiveness and cultural infusion that enriches the spirit of hip hop.”

Now that’s elevating Asian hip hop and graffiti.

[Images via MC Yan, Graffiti Research Lab, Stanley Wong & Plumber King]