Features

Features

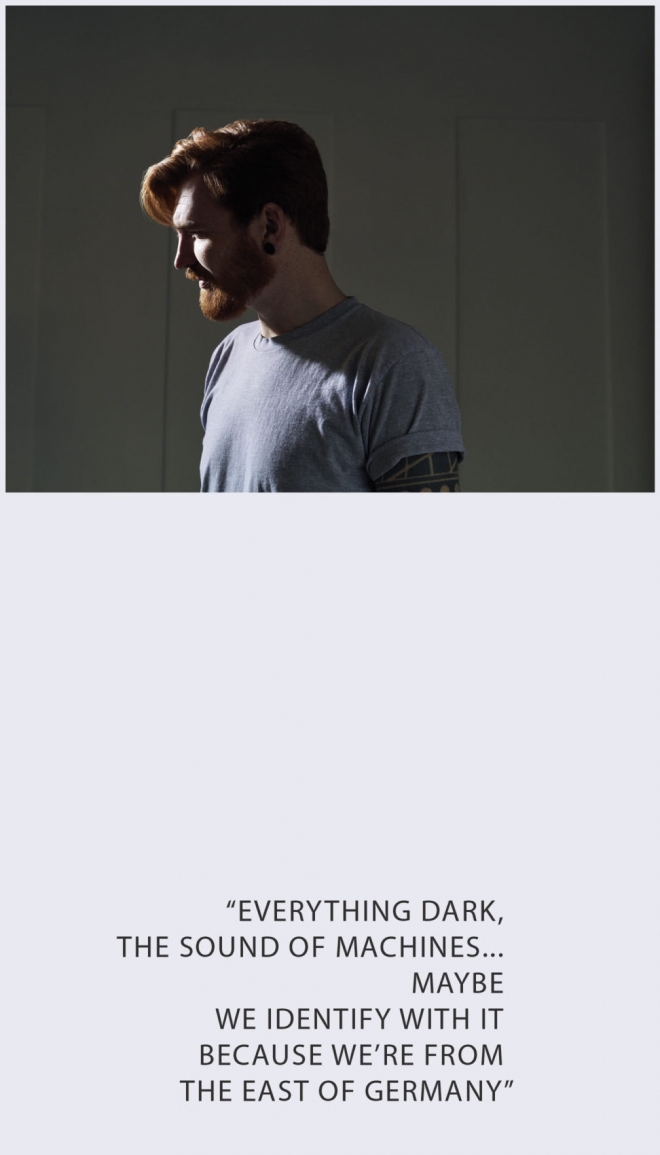

Everything dark: The rise of Rødhåd

Rødhåd’s outsider graft and visions of dystopia have made him one of the leading techno stars on the planet

Bierbach’s solution had been to build his own night. Despite having made a name for himself as a DJ rather than a producer (still, he believes, the central tenet of his identity), it took the best part of a year for plans for his own party to come together – largely because he couldn’t think of the right name. “I knew that once we started I’d need the design to be right as I wanted to keep this identity for a long time, to develop it as a record label and eventually release music,” he says, displaying a ruthless amount of fore-sight. “It took maybe six or seven months to come up with one. There were a lot of meetings where we would sit down and plan what we were going to do, but we couldn’t start because we didn’t have the right name.”

Luckily Bierbach already had in place the close-knit crew that still surrounds him. Their shared experience would help them find the right identity and their long-standing association would help usher the Dystopian night and label into being. Mike grew up in the new housing estates of Hohenschönhausen in the far East of Berlin with his father, a metalarbeiter (metal worker), his mother, who works in the financial system and older sister, and, despite not fully recognising its significance at the time, he remembers the fall of the Berlin Wall when he was six years old. “We moved there when I was one. My parents were living in Prenzlauer Berg before. At that time it was right next to the Wall, although now it’s quite a hip area, very expensive. But in the time we lived there it was kind of fucked up. The toilet was outside and the heating was the oven.”

It would be in these housing estates that he would develop a love for dance music, firstly gabba. “It was hard, radical,” he says unashamedly; “a lot of East Germans identified with it. It sounded like East Germany. Brutal, destroying.” It was on these estates where he would first try out his friend’s turntables (he bought his own when he was 15) and forge enduring friendships. “In the area where I grew up we didn’t have any people from West Berlin, so I was surrounded only by people from the East. The guys where I grew up were really rough, working-class people, you know? Maybe after school, when I started my ausbildung[apprenticeship], that was my first real contact with people from the West.” Bierbach’s ausbildung took place in an office where he learned how to do construction drawings for architects. It was a typically practical shoe-horning of his artistic sensibilities into a career path. “When I was younger I was really into graffiti, so it came from my love of painting and writing,” he says; although he recalls, with a smile, that “it soon turned out that I didn’t actually have to paint or write anything, because by this time everybody was already working with computers.”

Dystopian’s label manager (who, like his tour manager, firmly shies away from telling us his name, despite his integral part in Rødhåd’s story), recounts being impressed by his dedication to his day job at the time. Drawn together through music, he recalls that many others he met at the same time, through art or music, would solely inhabit those worlds, eking out existences on social benefits. “But as an artist it’s not really easy,” says Bierbach. “You don’t have a regular income, and I actually wanted to make money so I could buy records and have my own apartment. Also I liked the job, because I’m really into technical stuff.”

Bierbach would keep this parallel pursuit that paid for records right up to 2013. Unlike the foresight shown in the founding of Dystopian, he had never had a grand plan of becoming an international DJ and devoting all his time to techno. That only became an option with his increasing popularity. “The first real parties we’d done were ones we put on ourselves,” says Bierbach of his first forays while still a teenager. “We had another friend who was working at a company which rented out sound-systems. At the weekend he’d just get transport, put a soundsystem in the back and we’d go to a field not far from where we lived and set up for maybe fifty to eighty people. We had a little tent and a small desk, turntables, the soundsystem and that’s it. We weren’t thinking about doing crazy stuff with lights; it was just about the music.”

Although their parties these days are a lot less basic, that same emphasis on music above everything else is still evident. It now comes with an industrial, bleak and futuristic aesthetic that’s evident across all Dystopian activities, from their choice of venue to the artwork that adorns the label’s releases and the night’s promotional posters and flyers (which they still insist on producing, despite admitting social media makes them unnecessary).