Culture

Culture

Don't give up the day job? A new generation of DJs are working 9 to 5 without compromising their music dreams

Electronic artists are combining a music career with a day job and succeeding on their own terms

“Go back to the day job!” a drunken punter once shouted at Liam Wax, who was DJing in the heart of Hoxton. But this was Liam’s day job: spinning classic pop and up-front party bangers to East London’s itinerant weekend mob in order to fund his career as Desert Sound Colony, a rising star in the new wave of UK tech-house and breaks.

Liam left that life behind last year, becoming a full-time touring DJ and producer and clocking up two appearances at Panorama Bar, after the Hoxton venue’s new manager forgot to book him in and he realised his ‘real’ DJ diary was looking rosy. “I travel a lot now, and hear DJs complaining about all sorts of things,” he says. “That job definitely helped me get perspective.”

It’s a stark fact that the world of professional DJing currently reflects the wider world. Writing a Facebook post last year about rejoining the casual workforce, Detroit-raised Eric Cloutier was part of a Mixmag feature in 2019 on how sky-high headliner fees have slowly been strangling lower tier artist’s ability to make a living from music. Many DJs juggle nocturnal activities with full-time or part-time work. How can jobs help and hinder success? Is everyone suited to DJing and making music full-time? And if you had the chance to give up the day job, would you?

As half of London-based duo Souvenir, Elle Andrews is used to playing alongside a diverse range of DJs from Joy O to Cosmo Vitelli, with Souvenir’s bi-monthly Lyl radio slot showcasing their dark and percussive sound. During the week, though, she’s a photography teacher in a state school, a profession that “is challenging on its own without DJing as well.” Conservative funding cuts mean class sizes have grown in recent years, and school days got longer. “It’s not been unusual to work a 50 hour week, then do two gigs at the weekends,” she says.

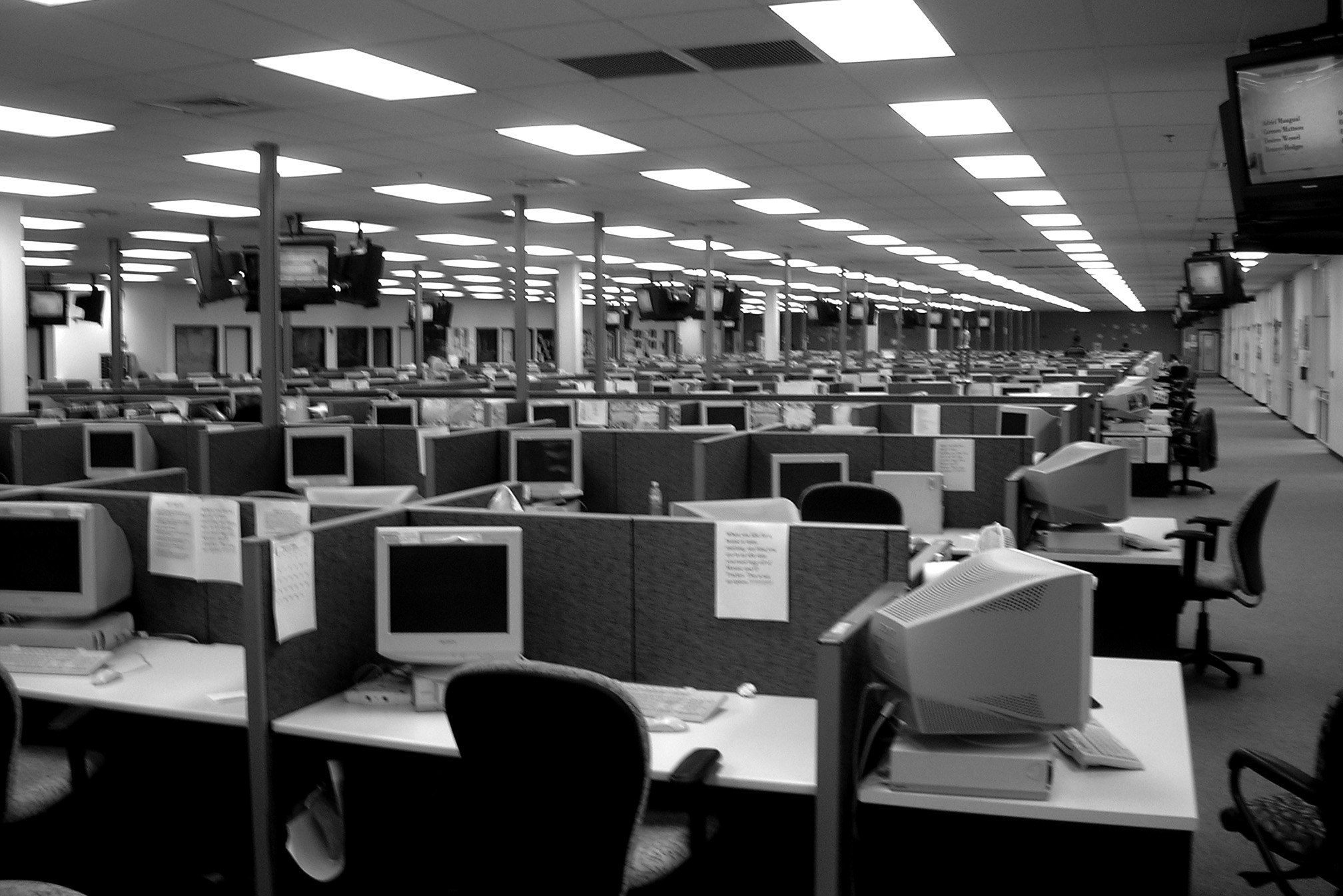

Desk-bound drone jobs might allow secret Discogs digging and listening to music on headphones, but there’s none of that in front of a class. “If I had to make a decision between music and teaching, it would be excruciating,” she says, though, praising her school for allowing her to work in a flexible and experimental way, and adding that it’s inspiring work when not too stressful.

This sort of creative intertwining accounts for the DJ/graphic designer, a seemingly even more ubiquitous career combination than DJ/drug dealer (except in tech-house circles, perhaps). Handling your own design cuts costs, adds work to the portfolio and helps focus your brand to cut through today’s crowded marketplace.

“I love playing, but I hate everything else around it,” says Trevor Jackson, who started out designing the UK covers of some of the earliest house records by Todd Terry and Raze. Today design is his bread and butter: his re-branding of Defected, for example, helped them re-emerge as one of the world’s biggest labels. Alongside this he’s a renowned DJ, last year gracing the decks of Atonal and Berghain, and playing alongside the likes of Andrew Weatherall and Optimo.

Yet as someone who has never taken drugs and misses home comforts so much he’s never played a gig on two consecutive nights, DJing is a career he’s never been prepared to throw himself into fully. While contemporaries like 2ManyDJs grew into festival headliners, Trevor has remained a niche star, his fortnightly NTS show featuring uncompromising sounds and keeping him in “the fortunate position of being able to play one or two gigs a month, even though I’ve never had a hit record and don’t sell a lot of records. I have a fairly good underground following and that’s enough to keep me going.”

So being a multi-hyphenate helps – and who achieves anything these days without a firm grasp of technology? Last year might have been the 12th consecutive year of vinyl sales growth, but the majority of the dance music world is now digital, both in DJing and production. “At Native Instruments they basically trained me to make synths,” Objekt told Mixmag of his time with the German software company, a job that’s essentially the equivalent of a secret in-game cheat code. Both he and Avalon Emerson, another former software developer, have turned the methodical mind-set involved in this career into a passion for meticulously playlisting their USBs – and kept their day jobs going until combining them with the demands (and opportunities) of a full time DJ/production career became essentially impossible.

But for some, the idea that you have to choose isn’t a given. When Auntie Flo, aka Brian d’Souza, left university after studying psychology and sound design, he set up his company Open Ear, a music consultation and playlisting company, to avoid getting “a proper job”, and continued DJing at weekends. As both business and career grew, there was a point around 2011 when he faced a dilemma. “Could I be a lot bigger as a DJ if I just focused on that? Would my business be bigger if I didn’t DJ?” he asked himself, aware that having employed staff it was about more than just his own future. “Eventually I didn’t bother to make a decision and just did both.” Sustaining his own living cost through DJing, Open Ear’s profits have now allowed the business to employ 15 people.

“The time constraints help my creativity,” says Brian, explaining that his output has been greater than some friends who pursued the dream of moving to Berlin and adopting the all-black outfit of the 24/7 DJ producer. “It stocks up my creative levels, so when I do get a moment in the studio all this stuff comes out of me.” The financial security of a day job also protects him from the pressure to follow every current trend to achieve some kind of perceived commercial success. If this has all been full-on, though, his work load just went up again: “Now I’ve got a baby, which is like three full-time jobs!”

Having it all can be unsustainable, especially with a family. Stu Robinson had already enjoyed a fair amount of success as a DJ as Cosmic Boogie when he started again as Asok in 2013 and set himself the challenge of making music. With three kids and a wife, his web development job meant he could work from home, making music in the evenings, and was technologically savvy. Within a few years he was also DJing two or three weekends a month. “I toyed with leaving my job all the time, but I had a mortgage and a family I wanted to support,” he says.

But the energy and time he invested in this, possibly exacerbated by what Stu later discovered was severe ADHD, helped precipitate the breakdown of his marriage. Today, prioritising seeing his kids, he has a new agent and a forthcoming release on DVS1’s Mistress Recordings – but there’s an attitude that his enduring passion for music can now “inflate and deflate as it sees fit without me needing to beat the drum to support me financially”.

Record shops have long been the launch-pad and lair of the DJ, from the dubstep pioneers at Croydon’s Big Apple to Beatrice Dillon’s time at the likes of Rat Records and Sounds Of The Universe, and Phonica’s alumni like Heidi and Saoirse. Proteus, aka Judith Klempner, has been gathering momentum with her gothic techno sound, and has recently begun to experiment with making music too. Part of the Shoreditch branch of second-hand shop Flashback Records, the flexibility over time off suits her as a touring DJ, along with a library of influences and an environment where most of her fellow shop workers make or play music. “I’ve been diving into loads of acid and jungle, doing lots of research,” she says, comparing the shop’s fun vibe to the store in the movie High Fidelity. “The randomness is great, because you never know what’s going to come in.”

It’s the ideal partner to a rising DJ career, yet she’s also clear she “wants to stay selective about what I do” in regards to gigs, meaning she’s open to combining DJing with a music job in the long term for financial security – perhaps eventually working at a record label. “I’m still working it out,” she admits.

Like many, Felix Yoosefinejad, aka Moleskin, supported running his label Goon Club Allstars through working in bars, then managing venues; now he works at Hub67, an East London community centre. Though he says he’d love to spend all day making music and DJing, the potential pitfalls – such as being co-opted by big brands in order to survive – have stopped him fully committing; right now, the vital projects of his current job remain aligned with his personal values. Instead, after 10 years of making music (his most recent release as one half of Handsome Boys), he defines his success as “affecting culture at the highest level. So... Kanye West messaging us. Or Beyoncé using a DJ Lag track we put out on her last album. It shows we’re platforming really good music that is relevant culturally.”

Brian mentions the advice of the accountant who helped set up his business, himself a DJ in his spare time. “He said, ‘If you want to continue to enjoy music, don’t work in music’. I’ve always remembered that, because it’s true. I still love music, but if I listen to it now I’m thinking, is that right for a playlist, is that right for a DJ set? There’s some sort of purpose. Very rarely is it just because I like it.”

And of course, everyone is different. Some artists will maintain that staking all their chips on their career taking off, getting rid of the safety net and taking that leap, was exactly the spur that led to success. But the message for the rest of us is that having a day job needn’t be at the expense of fulfilling your dreams in DJing or production. Just Google DJ Fingerblast’s ‘Customer Assistant’ and let one man repeatedly singing “I’m a customer assistant at Wilkinson’s” over a home-made version of The Human League’s ‘Don’t You Want Me’ if you need reminding that genius can still flower in the unlikeliest of workplaces.